People

Young Chinese Art Star Jia Aili on Why He Filled His New Gagosian Show With Paintings of the Apocalypse

The Beijing-based artist spoke with artnet News on the occasion of a 10-year survey at Gagosian in New York.

The Beijing-based artist spoke with artnet News on the occasion of a 10-year survey at Gagosian in New York.

Taylor Dafoe

There’s a moment in every post-apocalyptic sci-fi story when the main character realizes that his or her world—left ruined by a devastating disease or some nuclear tragedy—will never be the same again.

The work of Beijing-based painter Jia Aili exists in this moment.

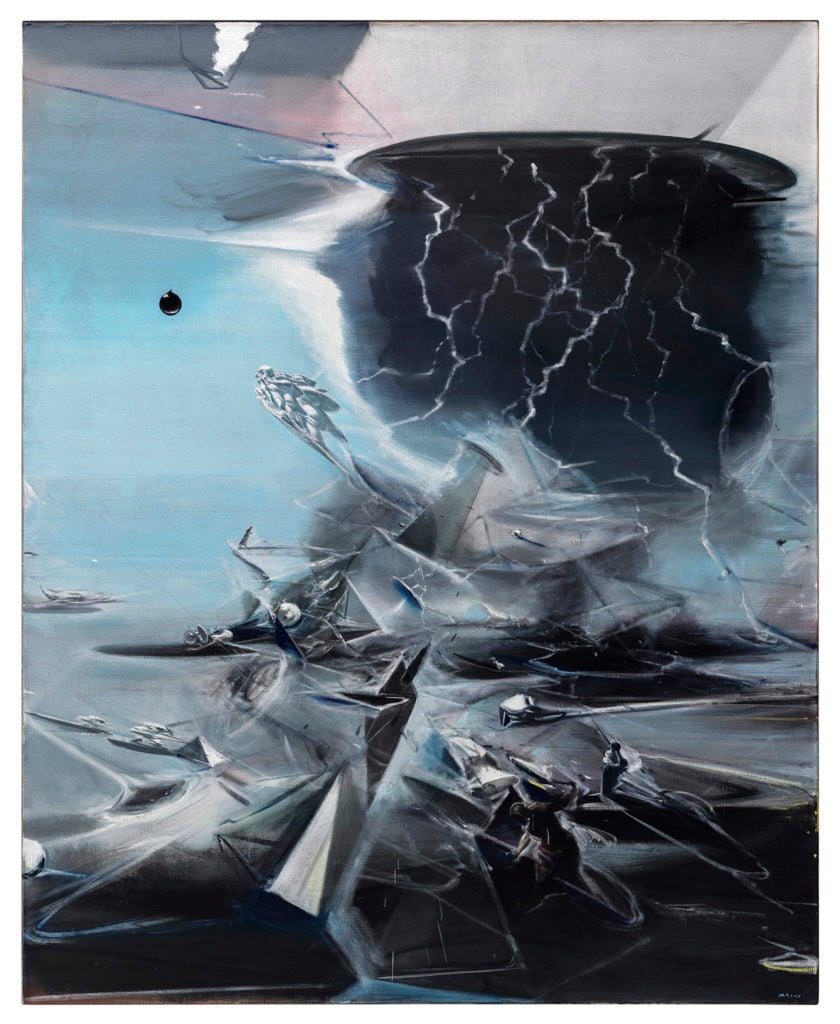

Walk into “Combustion,” his hotly anticipated current show at Gagosian, and you’ll feel it immediately. Canvases as large as billboards line the walls and most feature a dark, desaturated palette and a sense of anguish and Postmodern alienation that recalls the bleakest of Francis Bacon’s work. The paintings all seem to depict a dystopian world brought to the brink of self-destruction by technological innovation. The skies are black. The landscape is barren, save for the derelict remnants of industrial warfare. And characters, when they can be found, don gas masks and hazmat suits.

“Combustion,” which is on view through April 13, brings together 10 years of the artist’s work. It’s Aili’s first exhibition in New York—an impressive fact considering the financial and critical success he’s had in China and elsewhere.

Jia was born in 1979 in Dandong, a cold northeastern Chinese city on the border of North Korea, and studied at the New Representationalism Studio of the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts, graduating in 2004. He is a member of a new generation of Chinese artists, reared in the post-Mao Zedong era, who are known for eschewing the overtly political themes of previous generations in favor of merging classical Eastern modes of art-making with contemporary issues.

Though he spends the majority of his time in China, Aili maintains a studio in downtown New York. Camera in hand, artnet News met the artist at his studio to talk about his work, his ontological outlook, and the experience showing in New York for the first time.

Jia Aili, Sonatine (2019). © Jia Aili Studio. Courtesy of Gagosian.

This is your first exhibition in New York City. What has the experience been like?

New York is a wonderful and splendid city. It gathers people from different countries and cultures from around the world. It is a very novel and joyful thing for me to show my works to them. I have benefited a lot from the opinions and feedback of friends from different cultural backgrounds.

I was surprised to see in your New York studio that you had already begun to make several new large-scale paintings. How long do your paintings usually take, especially these larger canvases?

These works from the New York studio, such as the triptych that is still in progress, were all started last fall. In this work, I want to try to make an interesting visual model of everything I thought about and witnessed during my time in New York, such as ancient art in museums, Minimalist and Pop art, and street graffiti. They are all ready-made, inspirational material for me.

Usually, when the various materials of this thought process begin to establish a new connection, there is a break in the chain of logic. The process usually takes 3 to 4 years.

Jia Aili’s New York studio. Photo: Taylor Dafoe.

The sheer size of some of your paintings is impressive. At the same time, many of your canvases are also quite small, and the juxtaposition of the two dramatizes both. How do you approach scale in your work?

I often regard painting as the process of thinking and perceiving vision. Usually, with the recognition of information, the image I construct within the rectangular shape is continuously established and overturned. The perceptual correction and reconstruction of each prototype is performed, and it often returns to the singularity of visual appearance. This is how I have worked in recent years.

It is true that the visual construction required for a large work is complex and subjective, but it also benefits from the alienation of visual perception produced by gazing at a small piece of work.

What about the title of the show, “Combustion”? There are instances of combustion in many of the paintings in the show, although I’m curious about the title’s metaphorical significance for you.

Combustion in the general sense refers to the violent chemical reaction of luminescence and heat, and this process is also like the trajectory of individual consciousness. For me, it is more about Prometheus’s humanistic sentiment. Although this expression has been abused too much today, I am still willing to praise it without reservation.

Jia Aili, Hermit from the Planet (2015-16). © Jia Aili Studio. Courtesy of Gagosian. Photo: Chao Yang.

Given your existential concerns and your use of archetypal figures, people have described your paintings as having “universal themes.” Do you feel that they are universal? Do you believe art can transcend cultural, geographical, or ideological differences?

As Heidegger puts it, “Things can show themselves only if we do not attempt to put them into the box of the ideas we make.”

I was born at the end of the 20th century, where most ethnic groups in human society began to step out of the world of all-inclusive religious frameworks. In the modern world, for an individual, the physical body became highly compatible with society, but the spirit gradually lost its sense of belonging.

With the explosion of information that is now available to us, our perception has become both flat and rich. To some extent, the phenomenological tools that are widely applied to study liberal arts and humanities are very inefficient for painting, even though these tools clearly point to the pre-logic and pre-causal nature of the essential phenomena of the conscious world. It is still difficult to restore the occurrence and operation of visual experience in the ontology of painting—that is, the source and original intention of any construction and operation that is based on points, lines, and planes. Painting is not an inevitable result of a logical derivation.

At the same time, this work is difficult to dialectically analyze. Although painting is related to ideology, its fundamental purpose is to explore consciousness itself.

Jia Aili, Frozen Light (2017). © Jia Aili Studio. Courtesy of Gagosian.

You’ve said in the past that your painting process is as an act of discovery rather than one of creation from scratch. For you, what discoveries lead to a successful painting?

Painting is not a reproduction of the objective world, but meticulous care of the spirit—that is, the expression of humanity, a spiritualized language. I don’t want to associate painting with the functionality of the objective world. Just as Lichtenstein began to consciously draw a subjective and detailed description of the light that a man-made light bulb emits, we found an internal order of painting, that stands opposite of the objective world, and is gradually unfolding itself to us, and this order seems to be closer to spiritual reality.

There are 10 years of work on view at Gagosian. How do you feel your work has evolved in that time?

This decade is a gradual process of developing my artistic ideals. In terms of creation, although there are still many problems, I try to get myself into a more open state, to absorb more cultural nutrients. At the same time, I am also working on some new projects, such as group paintings with clearer thematic composition, including themes about the connection between the spiritual world and pure consciousness.

Details from Jia Aili’s studio. Photo: Taylor Dafoe.

Details from Jia Aili’s studio. Photo: Taylor Dafoe.

Details from Jia Aili’s studio. Photo: Taylor Dafoe.

“Jia Aili: Combustion” is on view through April 13, 2019 at Gagosian.