Art Fairs

1:54 African Art Fair Finally Gets the Stage It Deserves During Frieze Week

Now in its fourth year, the fair is over three times the size of its inaugural edition.

Now in its fourth year, the fair is over three times the size of its inaugural edition.

Naomi Rea

After too long neglecting the electrifying art scene across Africa, there has been a recent upsurge of international interest in the contemporary African art market.

In 2015, Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor was appointed the first African director of the Venice Biennale. Collectors and institutions worldwide are slowly starting to realize the extent of the untapped potential of the continent’s burgeoning art market.

Of the satellite fairs to visit during London’s Frieze week, “1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair” is a must. Now in its fourth year, the fair is over three times the size of its inaugural edition, an evolution that is a testament to African art’s growing cachet.

Showcasing more than 130 artists and 40 participating galleries—16 of which are based in the continent—1:54 presents a spate of offerings from newcomers and established artists alike. This year, Ghana, Ethiopia, and Egypt are all making appearances for the first time.

Touria El Glaoui, founding director of 154: Contemporary African Art Fair. Photo: © Victoria Birkinshaw, courtesy 154.

“It’s nice to see Africa being under a unified continent and everybody here representing their artists,” says founding director Touria El Glaoui. “This is what’s most exciting for me: this platform for collaboration, for people to meet institutions.”

Zak Ové, The Invisible Man and the Masque of Blackness (2016). Photo: Naomi Rea.

The fair that used to fit inside one small wing of Somerset House is now staged throughout the building and extends into the courtyard, with a site-specific installation of 40 sculptural figures by London and Trinidad based sculptor Zak Ové.

Inside the fair there is a lot to take in. On Wednesday, Somerset House was bustling, despite the preview coinciding with Frieze, and the elbow rubbing going on in the vibrant lounge was accompanied by the musical styling of Gilles Peterson’s new radio station, Worldwide FM, broadcasting live from the Revue bookstore.

Prices at 1:54 habitually range from £1,000 – £90,000, but heading the fair this year is a £600,000 drawing by Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi, Reborn Sounds III (2015), presented by Vigo Gallery. Upstairs, El-Salahi’s The Arab Spring Notebook is also presented in a non-selling show as part of the special projects by Modern Forms.

Victor Ehikhamenor, Oba Ovoramhen: Before And After (2014-16). Photo courtesy GAFRA.

At the booth of London-based gallery GAFRA, the works of Nigerian visual artist Victor Ehikhamenor are particularly striking. “This piece is a historical reference to the invasion of the Benin Empire whereby the king was deposed and sent to exile,” the artist tells artnet News. “So this is him going to exile, and the bronze added to the bottom of the feet are replicas the originals of which are still being held by the British Museum.”

It’s this uneasy relationship between past and present that creates such an impact. “Without trying to be confrontational, because a lot of water has passed under the bridge,” the artist says, “if someone comes to your house and takes all your jewelry and keeps it, and you know the person that has taken it and you guys are still co-existing, or maybe your great-great-grandchildren are still co-existing with their great-great-grandchildren, I mean, it should bother you.”

Victor Ehikamenor, The Gods will Sing and the People will Dance, (2016). Photo courtesy GAFRA.

Other works, such as The Gods will Sing and the People will Dance (2016), use an abundance of color, and cultural references.

“People might look at my work and say “Oh, Keith Haring!” or “Oh, Picasso!” but only because they don’t have access to what came before. They think I’m referencing them but my primary reference is in my DNA. These things were done by my ancestors, this is the way art was practiced then, and it is in my system. So that is it for me, that’s when things become problematic. Because people are not aware of what we have created in the past, they are now comparing me to someone that referenced us.”

Serge Attukwei Clottey pictured in front of I Shall Return, (2016). Photo: © Victor Raison, courtesy 154.

In the East wing, Accra-based Gallery 1957, named for the year of Ghana’s independence, showcases the work of Serge Attukwei Clottey, whose works centers around themes of modern consumption and consumerism.

“These are made of parts that I collected from all over the city,” the artist says.

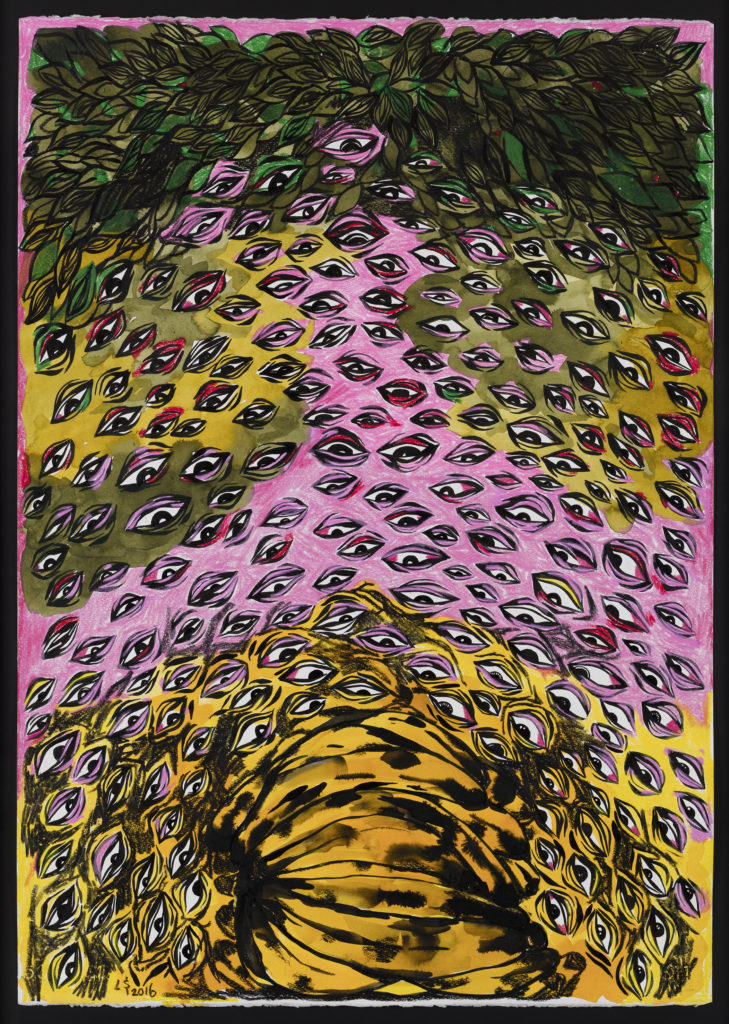

Lady Skollie, Viewing Pleasure IV: an ode to the thirst and the relationship complications associated with quenching your thirst without permission, (2016)

Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

Other remarkable works are the mesmerizing paintings by South African artist Laura Windvogel, aka Lady Skollie, in the Tyburn Gallery, JP Mika’s colorful portraits and the large scale, heavily layered paintings on offer from Galerie Cécile Fakhoury and Jack Bell Gallery.

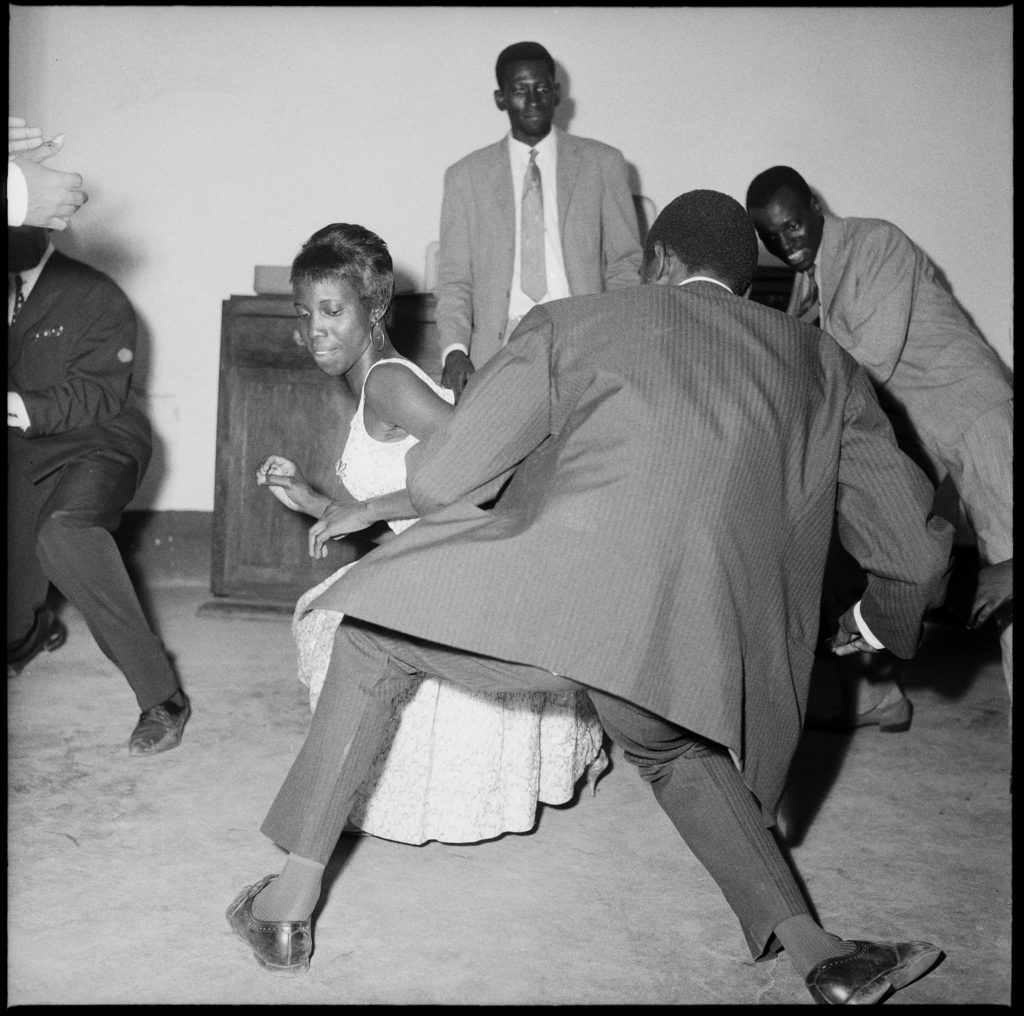

Malick Sidibé, Dansez le Twist, (1965). Photo: © Malick Sidibé, courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris.

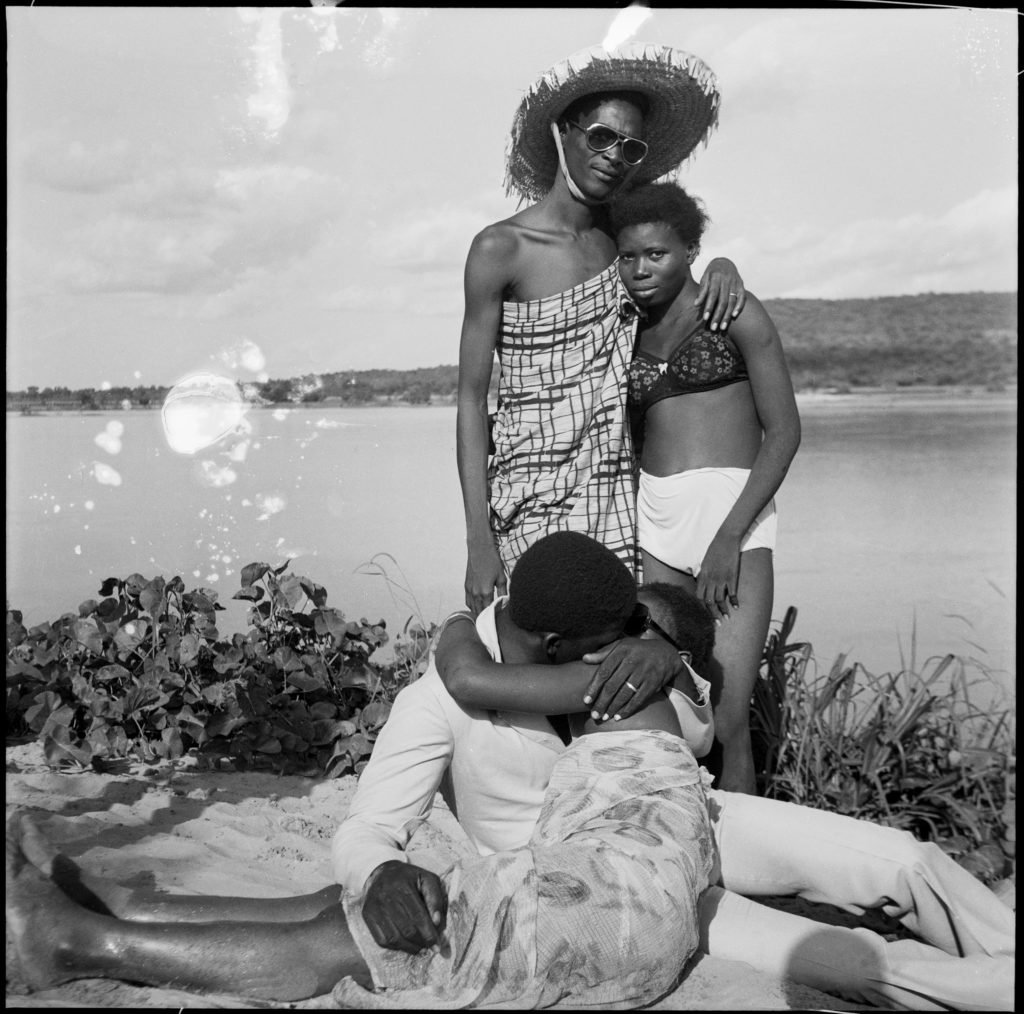

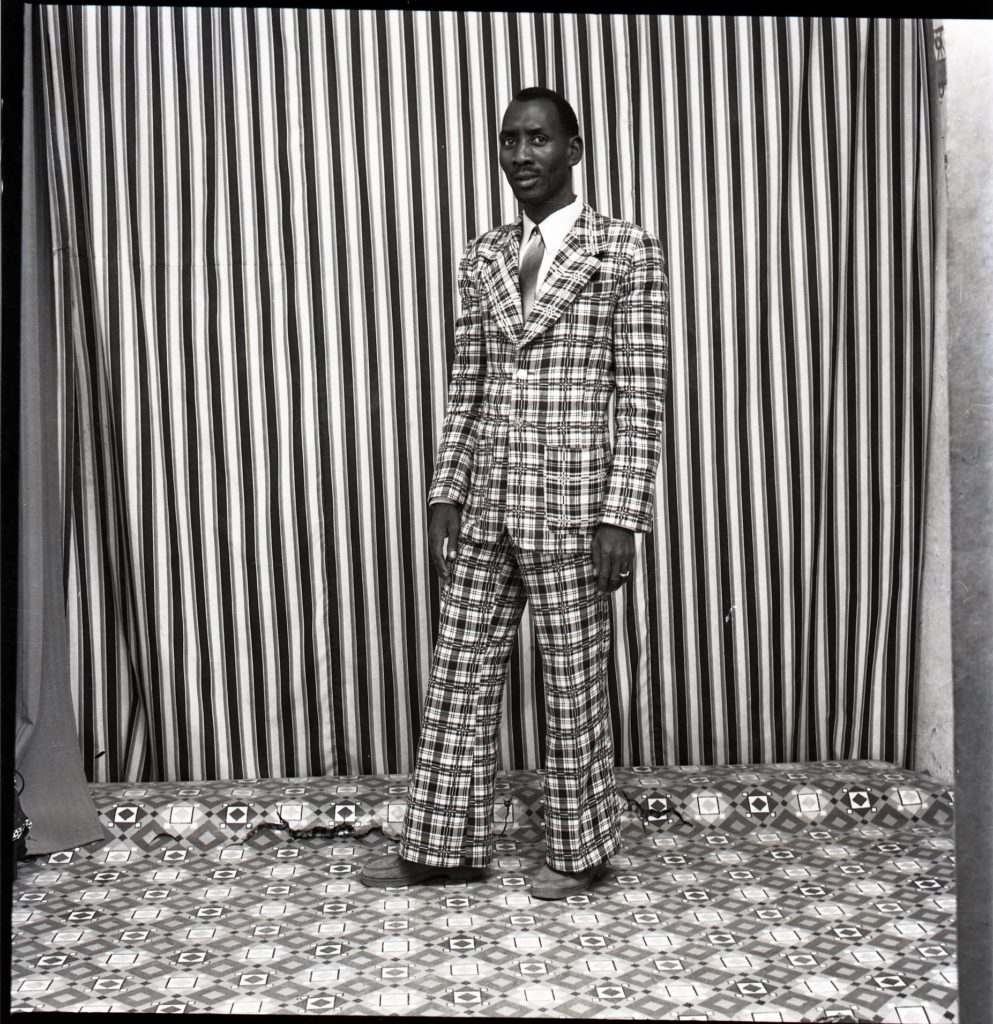

Highlights of the special projects include the first UK solo exhibition of the late Malian photographer Malick Sidibé, which will be on view until January. Dubbed the “eye of Bamako,” Sidibé’s work explores life in post-independence Mali, capturing the vibrant weekend parties that would spill into lazy Sundays by the Niger river, as well as the many portraits taken in his Bamako studio.

Malick Sidibé, Les Retrouvailles au bord du fleuve Niger, (1974). Photo: © Malick Sidibé, courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris.

Malick Sidibé, A moi seul, (1978). Photo:© Malick Sidibé, courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris.

The show is underscored by a specially commissioned soundscape by DJ Rita Ray, projecting the sounds of swinging ’60s Mali, when Sidibé was working.

Sokari Douglas Camp, Primavera, (2015). Photo courtesy Naomi Rea.

As for sales, the 1:54 director remains coy. “We don’t reveal numbers here,” El Glaoui says, “but I think so far we’ve had an amazing first day, knowing that we open at the same time as Frieze.”

She continues, “We’ve made such amazing progress; when I see where we started and where we are today, we are doing well. But it’s hopefully the beginning of a nice, high, curve, going up and up and up.”

1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair is on view at Somerset House, October 6–9, 2016.