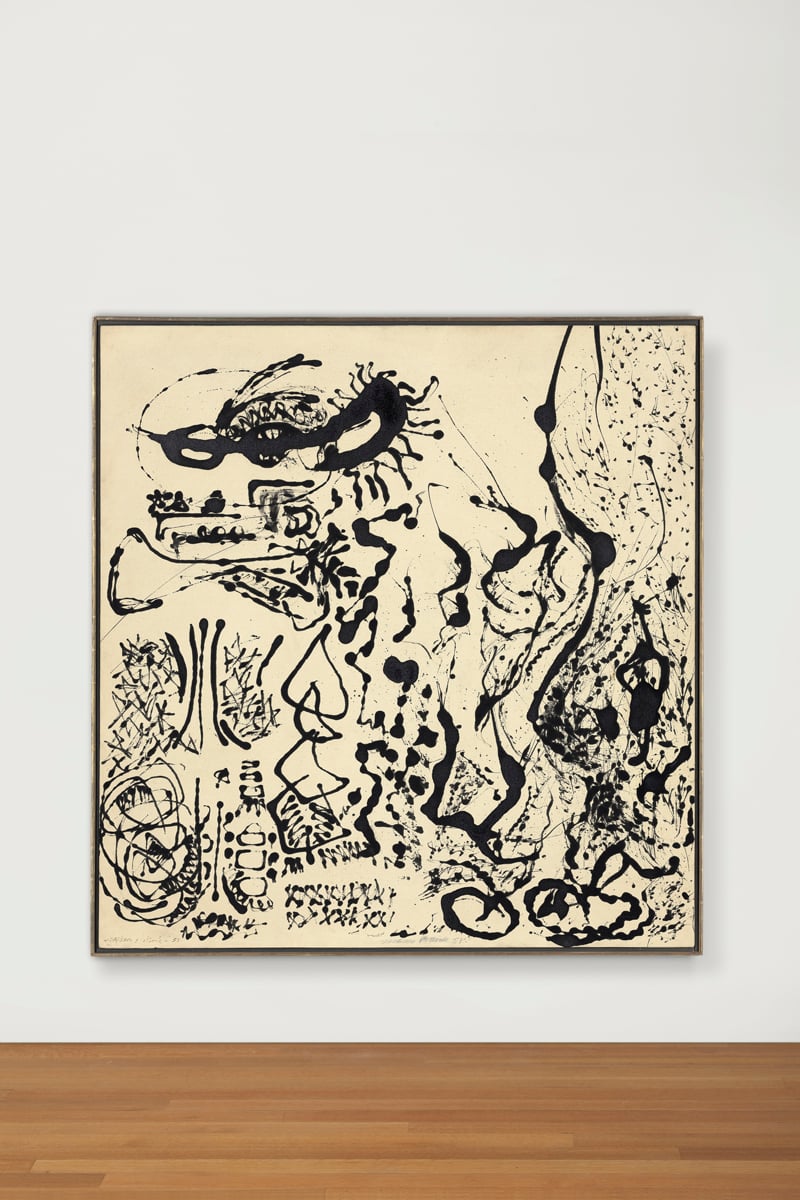

After 34 years in the collection of German energy concern E.ON and more than ten years on loan to Dusseldorf’s Museum Kunstpalast, Jackson Pollock’s Number 5 (Elegant Lady) (1951) will hit the auction block at Christie’s New York evening sale on May 13. The Pollock is the pinnacle of E.ON’s collection and a much-loved painting within that of the Museum Kunstpalast. Speaking to artnet News Dorothee von Posadowsky, E.ON’s head of arts and culture, makes no secret of the emotions surrounding Number 5 (Elegant Lady)’s departure. “It’s sad for us,” she laments. “We are separating from our most precious piece.”

It’s an incredibly rare late work. And, it comes with the added, in not a bit morbid, provenance of having been traded by the artist to New York dealer Martha Jackson for her Oldsmobile convertible. Two years later Pollock and Edith Mezger died driving the car. Christie’s experts have estimated that it will sell for between $15-20 million. If recent tendencies by the major houses to place conservative estimates on top lots are any indicator, one could expect the work to go for much higher. According to the artnet Price Database, Number 5 (Elegant Lady) is the single highest quality so-called “black enamel painting” to come up for auction since at least the early 1990s, and possibly ever.

The end of the painting’s loan to a German public collection and its coming sale have led some to question not only the motivations behind this deaccessioning itself but also, and more generally, those of public-private partnerships in the museum sphere. Corporate funding is a relatively uncommon and oft-criticized practice in Germany. “One is a bit skeptical concerning public-private partnerships [in Germany], especially [of the scale] we have because they fear influence,” von Posadowsky explains.

Since 1998, the partnership between E.ON and the Museum Kunstpalast has been the country’s largest, at up to €1.1 million (US$1.5 million) per year. The support was recently extended for 2015-2017 but at a lower amount of €750,000 annually. That comes out to approximately one tenth of the sum the city of Dusseldorf contributes, yet for its money the company gets to select four of the 14 positions on the museum’s board of trustees.

Some have argued that the Pollock’s sale creates a gaping hole in Dusseldorf’s collections, but if it does, it’s unlikely to be noticed by visitors. The Museum Kunstpalast does not have the capacity for Number 5 (Elegant Lady) (1951) to be on permanent public view. It was recently shown at the Louisiana Museum north of Copenhagen. Due to the prominence of the painting, its sale is unlikely to have any effect on future opportunities for the public to see the work via loan. In fact, von Posadowsky argues that chiding companies or private individuals for retrieving loaned artworks will only have a deleterious effect on the number of loans in the long term. “A loan is a loan and it is not a present for forever,” she says. “If people are punished for giving loans, then I don’t think many people will” continue to loan art. She adds: “If you’re punished when you want it back, I mean, that is just crazy.”

The company does not have any other artworks currently on long-term loans to institutions. Max Ernst’s La ville (1913) is currently on loan to the Max Ernst Museum in Brühl, but only for a temporary exhibition. What they do have, however, is a swath of perturbed ex-employees who have been laid off in recent years as part of a consolidation effort by the company in response to dramatically shrinking profits (2014 is projected to see a 33 percent contraction for the year). This stems from Germany’s turn away from nuclear energy and increasing governmental and consumer demand for their supplies to come from renewable sources such as wind.

The result? Despite an overall projected bottom line of €1.5-1.9 billion, every expenditure, never mind donation, is under scrutiny by shareholders. “The sale is a sign into the company towards the employees and to the outside that E.ON will keep up its art and culture activities,” says von Posadowsky, but that, she adds, it will have to sacrifice in order to do so. The Pollock, she says, “was the only work that we have [of a value] where we can say [that] we can pay for our commitment in sponsoring and our cultural activities for the next years.”

She’s quick to assuage fears that E.ON is somehow profiting from the sale of the work, despite it having been purchased for only 1 million Marks (US$500,000) in 1980. “Already, €2.25 million are going to the museum in the first three years,” leaving around €12 million for their “many other cultural activities,” if the work reaches the upper bound of its estimate. Von Posadowsky says that other expenditures include exhibitions of young artists in E.ON’s buildings, maintenance of the existing collection of around 1,800 works, and new acquisitions. In the end, she suggests, the loss of the Pollock is a small price to pay in order to continue to support new production and one of her hometown’s most important institutions.