Market

The 5 Biggest Myths About the Chinese Art Market—and the Inconvenient Realities That May Give Investors Pause

The market for Chinese art is full of eye-popping figures, but the outlook is not as rosy as it seems.

The market for Chinese art is full of eye-popping figures, but the outlook is not as rosy as it seems.

Melanie Gerlis

This story originally appeared in the artnet Intelligence report, a new art market report created by artnet News and the artnet Price Database.

One morning at Sotheby’s Paris this June, an exquisitely detailed, painted Chinese porcelain vase from the 18th century—which had been discovered in a family attic in France and delivered to Sotheby’s in a shoe box—sparked a 20-minute bidding war before finally selling for €16.2 million ($18.7 million), more than 22 times its high estimate.

Later that same morning, a finely rendered calligraphy album of poems by Empress Yang, possibly dating to the Song dynasty (960–1279), sold for a staggering 166 times its high estimate, skyrocketing to a final total of €2.5 million ($2.9 million).

As high-flying works of Chinese art, these objects represent a category of the broader international market that has received more and more attention since the 2007 financial crisis, when swelling ranks of wealthy buyers from China began to pay vertiginous sums for such collectibles. But headline figures like these don’t tell the whole story about where the market for Chinese art and antiquities is headed.

An Imperial Yangcai Crane and Deer Ruyi Vase. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

In fact, it’s hard to discern the true contours of this market, because results from mainland Chinese auction houses are not always reliable, buyers don’t always pay what they owe, and the system of checks and balances is less rigorous than in the West. But new auction data allow us to look under the hood and get a more accurate reading of the health of the market and the evolving behavior of collectors of Chinese art. What is revealed is a very different marketplace than the one conventional wisdom portrays—and it’s not an entirely rosy picture.

Below, we break down the biggest misunderstandings about the Chinese art market to show you the realities on the ground.

On the surface, it all looks fairly robust. In 2017, auction sales of Chinese art and antiques reversed two years of decline—which had coincided with similar downturns around the world—and grew 7 percent year-on-year, to $7.1 billion, according to the latest Global Chinese Art Auction Market Report produced by artnet and the China Association of Auctioneers (CAA).

Beneath the banner figures, however, there are signs that the recovery of Chinese art could be a bit of a dead cat bounce. First, the total is still down substantially from the market’s record high of more than $10 billion in 2011. Second, the numbers—as in the rest of the global art market—are considerably distorted by a thin top end.

Within China, the smaller houses, which are responsible for the majority of transactions, are struggling to make ends meet. The number of registered auction houses might seem large—CAA reported 525 on the mainland in 2017, compared with just 93 in North America. But more than 200 of these are “in hibernation,” meaning that they exist on paper but held no sales that year.

© 2018 artnet.

Meanwhile, sales of Chinese art and antiques outside China grew 8 percent in 2017. But according to Ning Lu, vice president of operations at artnet and the author of the CAA report, if the top 0.5 percent of lots that sold above ¥10 million ($1.4 million) are stripped out, the total revenue from overseas sales actually fell 12 percent. In other words, the activities of a very small handful of billionaires are obscuring the view of a struggling market below.

It’s important to consider two very different markets for China’s art: the mainland one, which is vast but very tricky to navigate, and the more accessible overseas market, including Hong Kong, which attracts a broader geographic pool of higher spenders.

Despite their growing presence in Hong Kong, even the big guns from the West have had trouble going deeper into the market in China. Sotheby’s, which opened a joint venture in Beijing with the state-owned Gehua Art Company in 2012, hasn’t held an auction there since 2013. “We have a long way to go before making Beijing and Shanghai as competitive as Hong Kong,” Kevin Ching, the chief executive of Sotheby’s Asia, acknowledges.

The opening ceremony of Christie’s at the Ampire Building in Shanghai, 2014. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Christie’s presence is also limited. The auction house landed in Shanghai to much fanfare and ribbon cutting in 2013, but it now has just one dedicated week of sales and events each year, in September. Rebecca Wei, president of Christie’s Asia, emphasizes her auction house’s commitment to the country but defines its presence as mostly a brand-building exercise for now.

There doesn’t seem to be much of a rush to change this strategy. Not only are the logistics problematic—for instance, overseas auction houses are barred from selling cultural relics on the mainland, including anything that predates 1949—but buyers in China are also feeling less flush these days.

Stocks on the country’s Shanghai composite index have been tumbling since January, and economists are predicting that the soft market will last through the year. “My clients who work in China’s finance sector are saying the big difference from last year is that there’s a lack of cash right now,” says one Hong Kong-based art adviser, who asked not to be named. “The stock market’s performance has been very bad. These are the resources that collectors would normally use to buy art.”

Buyers from China have also shown a taste for shopping for art outside their own country in recent years. In addition to the more streamlined process, they have been swayed by the quality of goods available elsewhere and the status that comes from buying in a hub like New York or London.

Auction houses have long been dogged by chronically late payments from Chinese buyers—not to mention promised payments that never materialize at all. The bad news: payment default and delay are only getting worse.

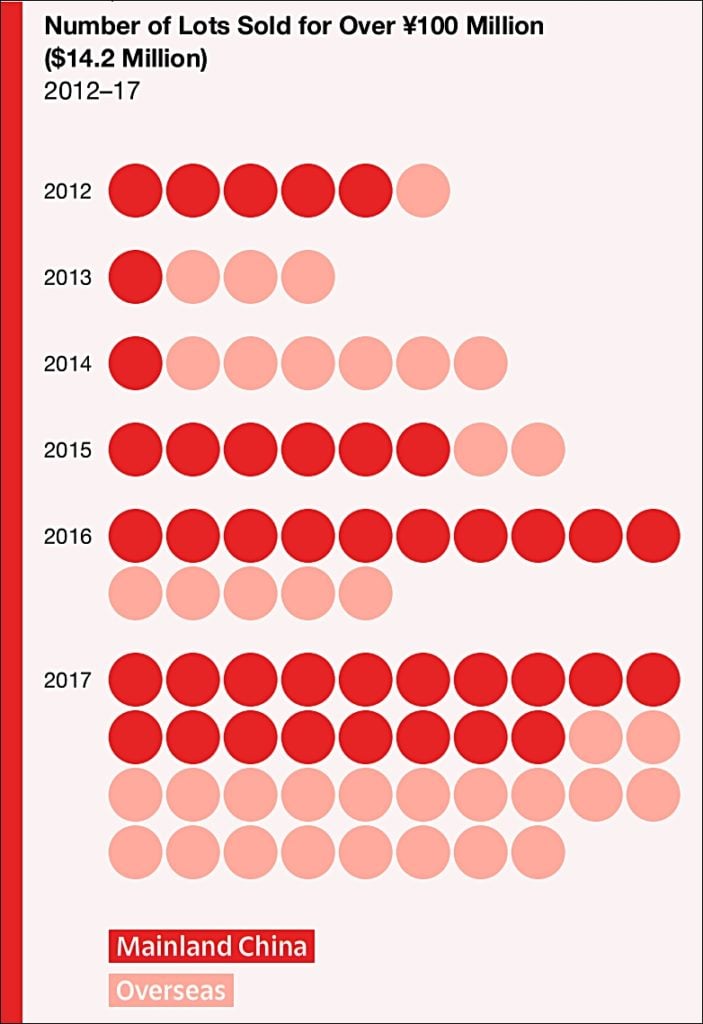

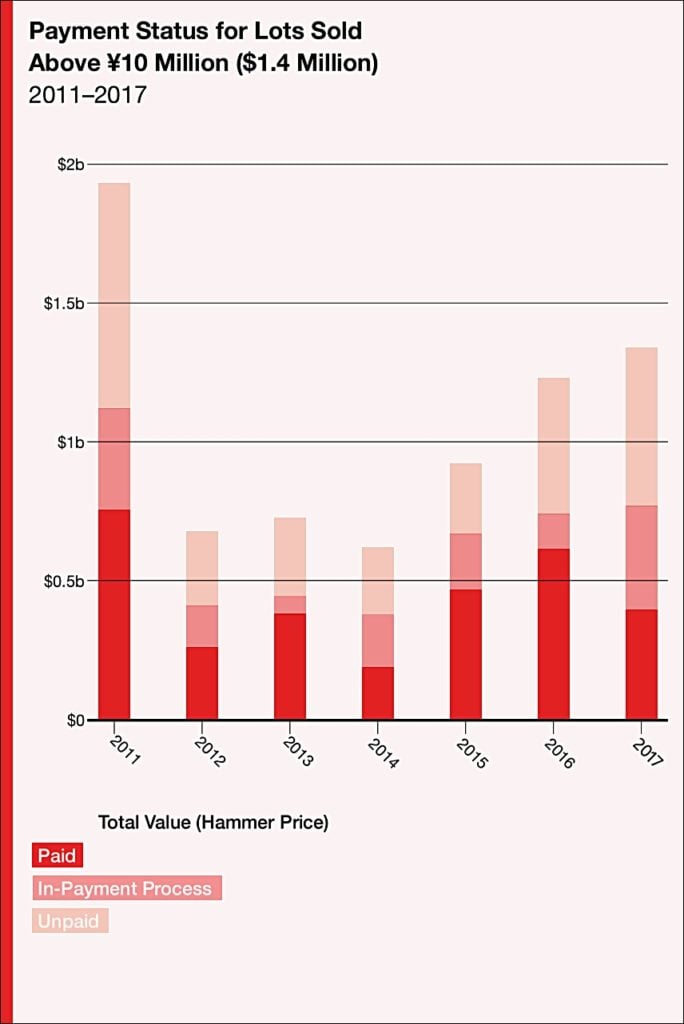

According to the most recent data, which CAA verified against tax filings, more than half of all money pledged at auction had not actually been paid nearly six months after the winning bids were placed. Analyzing data from 358 auction houses, the artnet and CAA report finds that 51 percent of the total value of sales on the mainland in 2017 had not been fully paid up by May 15, 2018, an increase from the already dismal 49 percent in 2016 and 41 percent the previous year. Of the 18 lots that sold for more than ¥100 million ($14.2 million), only two were paid for in full by this time.

© 2018 artnet.

Nevertheless, research suggests that the growing problem may be more nuanced than it seems—and that the blame for nonpayment may not rest solely with the absentee buyers.

Clare McAndrew, the founder of research firm Arts Economics, attributes the problem not so much to an unwillingness (or inability) to pay, but rather to the hefty onus that China’s auction houses put on buyers to determine the authenticity of works they purchase.

This dynamic is laid out in a disclaimer on the website of China Guardian, the country’s second-largest auction house, which notes that the company “cannot guarantee the genuineness, quality, and value of the lot, and the company shall not bear any warranty liability for a defect of the lot.”

Chinese auction houses’ approach is unusual. While other houses around the world certainly limit their responsibilities to buyers in fine print, most promise refunds on lots that are later found to be counterfeit. “In a lot of cases [in China], people might ‘buy’ an item, then need time to get it looked into before they are willing to pay,” McAndrew suggests.

The Salesroom at China Guardian Auction House.

Chinese antiquities are popular targets for forgers in a country that has an ingrained culture of counterfeits across all sectors. In 2015, Xiao Yuan, a librarian at Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, pleaded guilty to corruption after removing 143 works that dated to the 17th to 20th centuries from the university’s gallery and replacing them with his own replicas—but his defense included the fact that the practice of forgery was rampant.

Buyers from Chinese auction houses—the only businesses permitted to sell pre-1949 art on the mainland—are especially likely to wait to pay until they get their items checked out, since older work is more vulnerable to forgery. And they may never pay if it turns out their objects’ authenticity is questionable. This is a different negotiating process than in other art market centers, where would-be buyers generally try to establish authenticity before committing to a work. (For comparison, note that Sotheby’s took only one buyer to court over nonpayment in 2017.)

In other words, Chinese buyers will continue to default on payments for as long as forgeries remain a problem in the market. For the moment, it remains unclear which problem is worse: forgery or nonpayment.

One side effect of all the red tape, defaults, and uncertainty surrounding the sale of art and antiques in China is the growing Chinese taste for so-called international fine art—which is heavily biased towards recognizable American and European names from the 20th century onward. The presence of big-brand auction houses and galleries in Hong Kong, plus the clout Art Basel has amassed in that city since 2013, have only contributed to this phenomenon.

“I would describe the market in China as stable for us, but Chinese buyers’ purchases of Western art have increased most significantly,” says Rebecca Wei. In the first half of 2018, 12 percent of total sales at Christie’s were made in Asia, while Asian buying as a whole accounted for 24 percent ($960 million) of worldwide sales for the same period. Of the money spent by the Asian buyers, Wei notes, 60 percent was for non-Asian pieces (including luxury items), up from 48 percent during the equivalent period last year.

A bidder at Christie’s in Shanghai. Photo: Peter Parks/AFP/Getty Images.

Phillips, which opened a salesroom in Hong Kong in 2015 and expanded its presence there this spring, saw its sales in the territory rise from $30.5 million in the first half of 2015 to $56.5 million in the first half of 2018. A record-breaking Hong Kong auction in May featured work by major names from China alongside art by such Western stars as Damien Hirst, Ugo Rondinone, and Cecily Brown, plus Danish furniture. Jonathan Crockett, Phillips’s deputy chairman for Asia, identified younger bidders (including millennial collectors) from mainland China as the driving force behind the successful sale.

To a certain extent, this kind of pendulum swing needed to happen, says Philip Tinari, director of Beijing’s Ullens Center for Contemporary Art. “There was a time [in the run-up to the 2008 boom] when Chinese collectors only had access to works by Chinese artists, which created inefficiencies. Some of the prices were not justified.”

Most Chinese artists—apart from a few high-profile contemporary practitioners—have experienced scant interest from Western collectors. And the mainland galleries that support and promote Chinese art have yet to make their presence felt much beyond Hong Kong.

Jennifer Flay, director of FIAC, in Paris, is proud to have four galleries from mainland China in the Grand Palais this month, one more than for the art fair’s last edition. They represent just a small percentage of FIAC’s 193 exhibitors, but the number is notable, considering the situation at competing fairs. This year’s Frieze London, for instance, had one China-based gallery (Magician Space from Beijing) among its 148 exhibitors. Galleries that promote older Chinese art barely figure on the international market.

Zeng Fanzhi, Van Gogh I (2017). © Zeng Fanzhi. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Market players are aware of the one-way traffic. Hauser & Wirth gallery may have only 2 Chinese artists on its roster of 73, but it is making a considerable push to promote them. Lihsin Tsai, the gallery’s senior director based in Hong Kong, points to its show of the Beijing-based artist Zeng Fanzhi, which appeared in Zürich, London, and Hong Kong this fall. It marks the first time the gallery has dedicated three spaces to one artist.

Meanwhile, institutional shows, such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s exhibition “Art and China After 1989” in New York last year, are also breaking new ground and exposing Western collectors to a more expansive, nuanced version of Chinese art history. On the commercial side, Gagosian’s New York exhibition of the 35-year-old Chinese painter Hao Liang, who gives a 21st-century twist to traditional Chinese ink-wash painting, sold out before it even opened, in June.

Wei expects this trend to continue, albeit slowly. “In the future, Christie’s will also try to promote more East to West, but it will take time,” she says. “The ecosystem is still forming in Asia.”

This story originally appeared in the artnet Intelligence report, a new kind of art market report created by artnet News and the artnet Price Database. The full report has even more juicy details about the Chinese market, from a breakdown of notable recent sales to an interview with David Zwirner Hong Kong director Leo Xu. For all that and much more about the international art market, download the full report here.