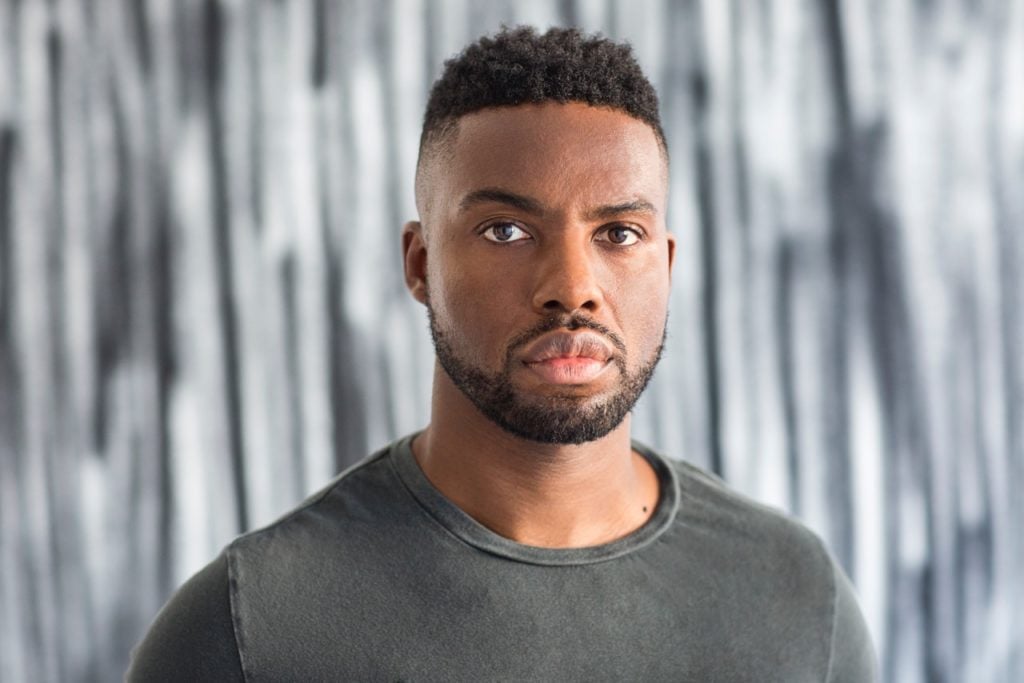

As Terence Blanchard made history last week by becoming the first Black composer to open a production at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, I visited another major cultural institution where a Black artist created “a total work of art for the 21st century.”

Adam Pendleton is the man behind, arguably, the largest and most ambitious visual art project in the city at the moment: Three 60-foot-tall black scaffold structures displaying paintings, drawings, and film in the soaring atrium of the Museum of Modern Art. The immersive work explores themes of Blackness, identity, and abstraction.

Titled Who Is Queen, it bursts into the temple of Modernism, at once a disruption and an homage. Its black and white imagery of text-based paintings and documentary footage of Civil Rights protests and the recently dismantled monument to general Robert E. Lee flickers as you ascend the floors and travel further back in art history. The soundtrack, which includes recordings of poet Amiri Baraka, Black Lives Matter protests, and the music of Jace Clayton (aka DJ Rapture), ricochets among paintings by Pollock and Picasso in the normally hushed galleries.

The MoMA piece is the culmination of the past decade for Pendleton, a conceptual artist with a disciplined approach to his practice and prices. Its visibility and scale are likely to push the artist’s career and market to new levels—while testing his ability to control both.

Installation view of “Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen?” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Andy Romer.

“To have MoMA in your corner is powerful,” said adviser Wendy Cromwell, who has placed three paintings by Pendleton with her clients in the past two years. “It’s a game-changer for artists in their careers. It helps validate the existing market. It has a potential to raise prices in the future.”

Pendleton, a native of Richmond, Virginia, is a bit of a conundrum. Only 37, he has spent two decades exhibiting widely around the world. His supporters include Whitney Museum director of curatorial affairs Adrienne Edwards, whose conversations with Pendleton formed the foundation for Who Is Queen, and Laura Hoptman, who invited Pendleton to participate in significant group exhibitions during her tenure at the New Museum and, later, MoMA.

But while his works are collected by Steve Cohen, Laurene Powell Jobs, Venus Williams, and Leonardo DiCaprio, Pendleton hasn’t had a solo gallery show in New York since 2014, and there isn’t a frenzied secondary market for his work. His $262,812 auction record was set two years ago at an auction for a nonprofit organization. Meanwhile, works by younger artists, with much shorter and less illustrious careers, have sold for many times that sum.

Unlike colorful figurative paintings by Black artists, which have ignited speculative trading in recent years, Pendleton occupies a more austere and heady space. In a recent profile, Pendleton told the New York Times, “I’m fine with being misunderstood. You can see it in my work—these fields of stuttering language. It’s a refusal, but it’s an invitation at the same time.”

Stuart Comer, MoMA’s chief curator of media and performance, calls Pendleton a rigorous thinker about politics, poetry, and gender theory. “It’s all there,” Comer said. “It’s this incredibly rich and broad intellectual spectrum that finds outlets to be activated within the work.”

Pendleton’s closest analogue might be Rashid Johnson, who has been classified as a conceptual, “post-Black” artist and also works across several mediums. However, Johnson’s work trades regularly on the secondary market, and earlier this year he achieved an auction high of $1.95 million at Christie’s for a painting, Anxious Red Painting December 18th, created during the pandemic and sold to raise money for a nonprofit.

The lack of auction heat around Pendleton “may be because he’s not interested in collaborating with luxury brands and fashion houses, or in being a DJ,” said Alexander Gray, an art dealer and Pendleton’s friend of 18 years. “It’s about the art. He really controls how much work goes out of the studio. He doesn’t want to be a vehicle for speculation.”

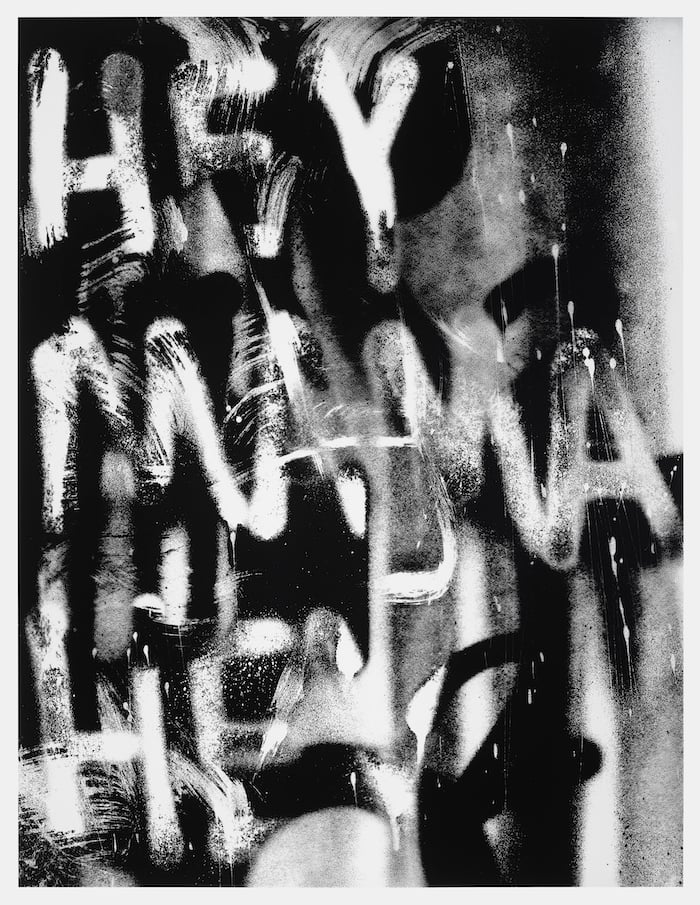

Adam Pendleton, Untitled (HEY MAMA HEY) (2021). Image courtesy of the artist.

It could also be a result of his focus on art, rather than on the market. Instead of feeding the beast, Pendleton often says no to distractions. At 16, he refused to get a driver’s license because he was too busy painting in the basement. In recent years, he’s said no to dealers asking him to make more paintings, charge higher prices, and do high-profile exhibitions. He even said no to New York City, moving upstate for several years in his 20s.

This uncommon talent for saying “no” is the result of Pendleton’s clarity and determination, said Edwards, his friend of more than a decade. Pendleton isn’t someone to hit the gala circuit or spend summers in the Hamptons.

“With that clarity you kind of know what fits and what doesn’t,” she said. “What’s going to be helpful to you and what’s not. Adam makes art because that’s what he has to do. He turns to literature and poetry because that’s what feeds him. The ‘no’ has to do with a determination to reserve that place for himself.”

Pendleton declined to comment for this column, but issued a statement: “Art is a slow process that demands time and attention. I’m not an artist for 10 years, but for the rest of my life.”

This kind of deliberation can be a headache for his dealers.

Pendleton makes “a painfully small number of paintings,” according to Marc Glimcher, president of Pace, the mega-gallery that has been working with him since 2012. “We might have a year where we get to have a show or two, so maybe there are 15 to 17 paintings,” he said. “Some years it’s less than that.”

Painting is only one aspect of Pendleton’s practice, which also includes performance and writing. All are rooted in his theory of Black Dada, which draws parallels between artistic response to the trauma of World War I in Europe and to racism in the U.S. He developed it in his 20s while leading a nearly monastic existence in Germantown, New York.

The market, however, is mostly interested in the paintings, and those take a long time to make. His process involves numerous stages and revisions, with spray painting, photography, and silk-screening.

“Maybe one out of three is acceptable to him,” Glimcher said. “He knows exactly what he needs to do, exactly how many paintings he needs to make. And it’s never in response to the market—which is very healthy, but a little frustrating for the collectors.” Prices for paintings start around $200,000 and go to $600,000 for a 20-foot mural similar to the one at MoMA, Glimcher said. (A work by the artist also sold for $333,000 on Loïc Gouzer’s Fair Warning app last year.)

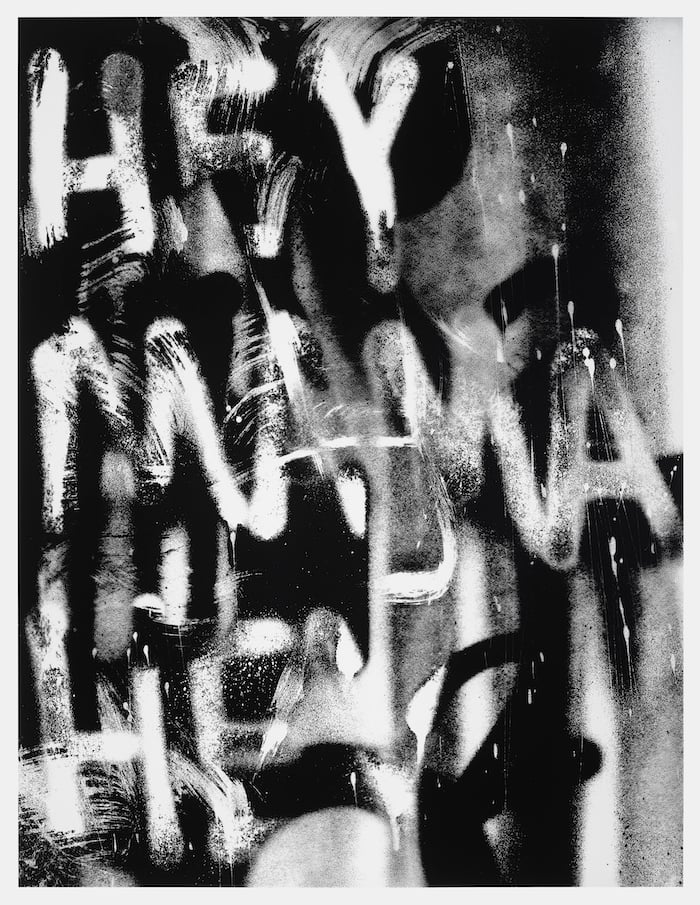

Adam Pendleton, Installation view of “shot him in the face” at KW Institute for

Contemporary Art, 2017. Photo: Frank Sperling.

Los Angeles dealer David Kordanksy got only nine paintings, an installation, and a film for Pendleton’s first solo show with the gallery last year. Everything sold. “From the market’s perspective, he would probably be perceived as an under-producer,” Kordansky said. “It’s ‘slow and steady wins the race’ with him.”

The tight control has repressed auction sales, according to Cromwell. With his MoMA show, Pendleton is on the knife edge of critical darling and market star, and there are signs he is shifting to meet the moment. In the lead-up to Who Is Queen, he began trickling out a new body of work, less austere than his earlier Black Dada paintings, with spray-painted text and more evidence of the artist’s hand. These, says Cromwell, “have dramatically increased the audience for his work.”

Of course, the very qualities that keep Pendleton’s market on a low simmer instead of a fast boil are the ones that make possible a work as complex and long-gestating as Who Is Queen. It required vacillating from solitary research to collaboration with a team of 20 people, including an architect, cinematographer, and composer, not to mention a small army of fabricators and art handlers.

“I’ve never worked with anybody quite like Adam,” said MoMA’s Comer. “He’s unbelievably focused. He lives his life with care and purpose and he produces his art with care and purpose.”