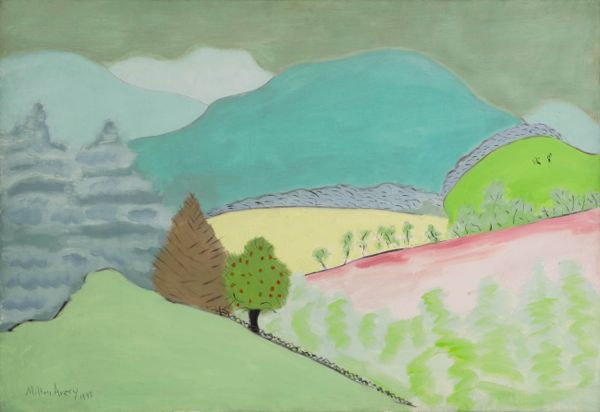

. Est. $1.5/2.5 million. Sold for $3,370,000.

Photo: Courtesy Sotheby's New York.

Solid results for American art in three very differently composed sales at Sotheby’s and Christie’s this week underscored the return to health of the market for a wide range of subgenres: modern masters, nostalgic illustration artists, and landscape painters who helped shape the myths of the American West.

The 89-lot Sotheby’s sale on Wednesday totaled $38,301,625, a hefty chunk of which came courtesy of the top lot, Georgia O’Keeffe’s White Calla Lily (1927). Hammering to a client on the phone with department head Elizabeth Goldberg for $7.8 million, or $8,986,000 with fees, it was still on the low end of the $8 million to $12 million estimate.

Georgia O’Keeffe, White Calla Lily.

Photo: Courtesy of Sotheby’s New York.

Sotheby’s set the standing record for O’Keeffe—and also for a woman artist of any nationality—last December when Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 (1932), achieved $44,405,000 (see O’Keeffe Painting Sells for $44 Million at Sotheby’s, Sets Record for Work by Female Artist and Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges Museum Bought Georgia O’Keeffe Painting for Record $44 Million). With no comparable marquee lots, the house was hard pressed to top its previous $75,395,499 take of six months ago, but demand was strong for works under $1 million, with active bidding on names rarely seen on the auction block.

An early tug-of-war erupted over Morton Schamberg’s pleasingly colored floral Still Life (1913) (est. $30–50,000), which one buyer chased to $237,500. Successes like this boosted the sell-through rate to 85.4 percent by lot, 94.4 percent by value. “It was just shy of our high end, with great energy both in the room and on the phones,” said department head Elizabeth Goldberg, who attributed the enthusiasm to the variety of price points and deeper-than-usual cuts from the canon.

Property From A Distinguished Private Collection. Maxfield Parrish, Norwich, Vermont

Photo: Courtesy of Sotheby’s New York.

Dealer Rick Lapham fended off stiff competition to snag Maxfield Parrish’s late, twilit landscape Norwich, Vermont (1954), which was offered on the block for the very first time. Estimated to fetch between $400,000 and $600,000, the final price was $1,030,000. Lapham had less luck with Parrish’s Two Cooks and a Haggis (n.d., est. $300–500,000), which went to a phone bidder for $1,570,000.

The sale’s leading Norman Rockwell, The Bookworm (Man with Nose in Book) (1926), which made $3,834,000, well over its $1.5 to $2.5 million estimate. (It was a nice garnish for consignors Roy and Sarita Warshawsky, whose collection of Tiffany and prewar design rang up some $8 million on Tuesday.) “This market is tough for both Parrish and Rockwell,” Lapham noted, shining a light on the high demand for classic illustration works; later in the sale, a John Philip Falter oil titled Sunday Picnic, Troy, Kansas (1945), which appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, nearly doubled its $120,000 high estimate to fetch $237,500.

Property from The Warshawsky Collection. Norman Rockwell, Man With Nose In Book (The Bookworm) (1926).

Courtesy of Sotheby’s New York.

On the 19th-century tip, Louis Salerno, of Manhattan’s Questroyal Fine Art, was pleased to walk away with five works: Ralph Albert Blakelock’s Stilly Night (n.d., est. $30–50,000), for $212,500 and his proto–Ashcan School oil Shanties in Harlem (1874) ($60–80,000) for $112,500; a pair of modest Alfred Bierstadts, and Jasper Cropsey’s Autumn on the Hudson (1887) (est. $20–30,000) for $28,750.

Of the Blakelocks, Salerno says, “They were two great examples, much better than what we’d seen in recent times, and I was prepared to be aggressive.” However, he added, “There’s still an absence of really high-quality 19th-century pieces. You get a lot of people saying the 20th-century work is more appealing or has a bigger audience, and that may be true, but it’s a bit of an unfair comparison, because you’re just not seeing the good older stuff. Our experience on the private market is that buyers are willing to strive to buy good paintings.”

On Thursday, Christie’s augmented a somewhat hit-or-miss various-owners sale with a separately catalogued offering of paintings from industrialist William I. Koch’s collection of Western art. Taken together, the $29,822,500 total for the 74-lot morning session plus $17,189,125 for the 68 Koch lots was satisfactory; however, the results would have been higher if either the top-touted Edward Hopper—the 1945 Cape Cod painting Two Puritans, which the house had hoped would realize between $20 million and $30 million—or Frederic Edwin Church’s Mount Newport on Mount Desert Island, painted in Maine circa 1851–53 and pegged at $5 million to $7 million—had succeeded in cracking their reserve prices. The guaranteed Hopper, said to sublimate his fraught relationship with his wife within a depiction of two white clapboard houses, was an especially pricey buy-in; observers blamed a too-high estimate for a piece that lacked the artist’s signature isolated figures.

Edward Hopper, Two Puritans (1945).

Photo: Courtesy of Christie’s Images LTD 2015.

Satisfying modern tastes while setting an artist record was Arthur Dove’s Boat Going Through Inlet, circa 1929 (est. $2.5–3.5 million), which made $5,429,000. “Nothing of this caliber [by Dove] has come up to the auction market,” noted department head Elizabeth Beaman. It hailed from the same consignor of Franz Kline’s $21,445,000 Steeplechase to the contemporary auction the previous week, and had hung alongside it in the collector’s home. The smallish, abstract oil on tin sparked a tussle between private dealer Michael Altman and adviser Megan Fox Kelly, who ultimately prevailed on behalf of her client, the Chicago-based Terra Foundation.

Georgia O’Keeffe, East River With Sun (1926).

Photo: Courtesy of Christie’s Images LTD 2015.

Bearing the same estimate as the Dove, a rare O’Keeffe grisaille watercolor from her New York City period, East River with Sun (1926), fetched $3,189,000 from a bidder on the phone with Maria Los, who beat out collector James McGlothlin, seated in the second row. “We’re seeing a new tier for American modernism,” observed art adviser Baird W. Ryan, who snagged Hopper’s charcoal drawing South of Washington Square, circa 1915 (est. $250–350,000), for $437,000, and William Bradford’s wonderstruck paean to exploration, Midnight Sun, The Arctic (1878) (est. $500–700,000) for $1,445,000. He predicted that the opening of the new Whitney Museum building, where much more of its collection of American art is on display, “will fortify the market for O’Keeffe, Hopper, and Andrew Wyeth.” (See Does the New Whitney Herald a Golden Age for New York Institutions? and 10 Fun Facts About the Whitney Museum.)

Still, there were takers on earlier landscapes and Western art. Near the end of the first auction, a half-dozen bidders jumped into the fray for cowboy painter Edward Dunton’s Glorietta (1924) (est. $100–150,000), consigned by heirs of the founder of Oldsmobile, driving it home to $497,000. The Cliffs of Green River, Wyoming, a breathtaking 1896 oil by Thomas Moran, a Hudson River School painter gone west, led the Koch session with price of $8,565,000, just past its $6–8 million estimate. The quality and imprimatur of the Koch works inspired tenacious bidding online and in the room, especially for Thomas Hill’s Attack on the Emigrant Train (n.d., $30–50,000), which more than quadrupled its $50,000 high estimate with a final price of $233,000. “We do see some of the younger, newer collectors entering the American art market through Western art,” said specialist Peter Kloman, “those based in Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado. It’s what they’ve grown up with.”

Given the sustained interest in so many different genres, attendees professed optimism that the American market had finally regained its footing after a stumble in 2009–12. Exiting the sale room at Christie’s, New York dealer Meredith Ward, an American modern specialist, praised the record result for Dove, whom she deemed “still undervalued,” and described the breadth of bidding at Sotheby’s as “very encouraging from the standpoint of the middle market. It’s not just blockbusters that people are after.”