Auctions

The Warhol Foundation Is Auctioning Off the Artist’s Computer-Based Works as NFTs. An Archivist Who Uncovered Them Is Outraged

The foundation contends that the NFTs are "the best representation of Warhol’s digital works."

The foundation contends that the NFTs are "the best representation of Warhol’s digital works."

Sarah Cascone

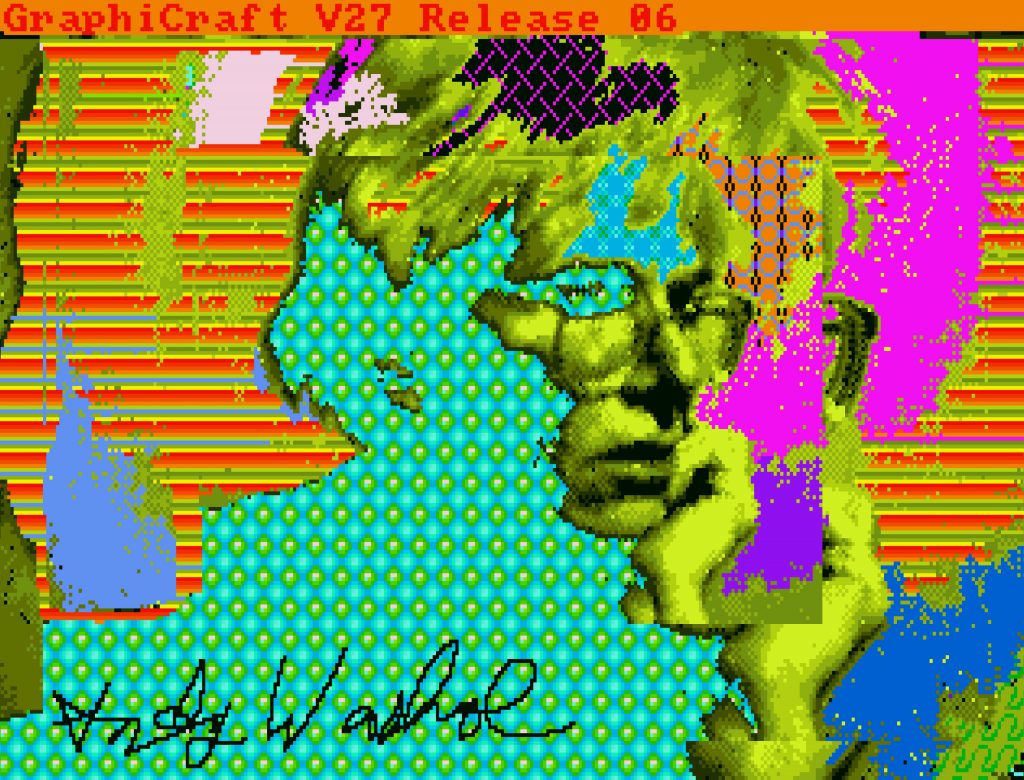

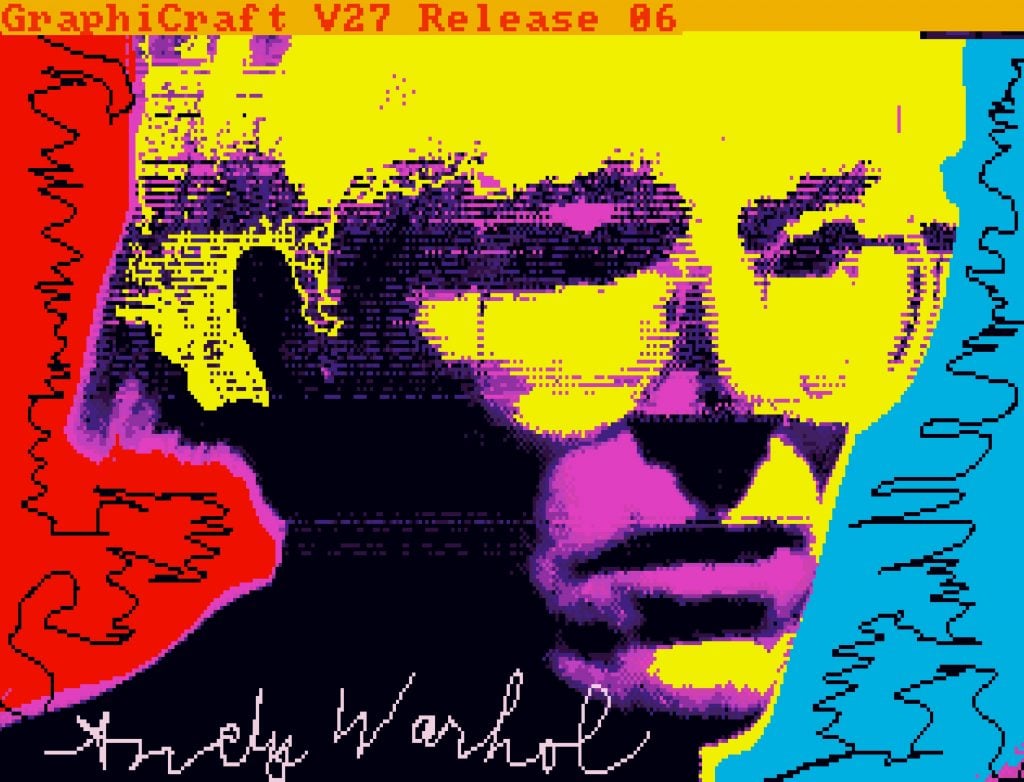

In 2011, artist Cory Arcangel set out to find a set of obscure Andy Warhol artworks—digital images the famed Pop artist had created on his personal computer, Commodore’s Amiga 1000, in the mid 1980s using a new computer software called ProPaint that was never actually released.

Against all the odds, Arcangel and a team of experts from the Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Mellon University Computer Club and the university’s Frank-Ratchye Studio for Creative Inquiry were able to recover the lost artworks, stored in an obsolete file format on floppy disks, and share them with the world.

Now, five of those images are being offered at auction by Christie’s New York, which is selling the early digital artworks as NFTs, offering collectors a chance to own Warhol art on the blockchain for the first time.

“As the great visionary of the 20th century who predicted so many universal truths about art, fame, commerce, and technology, Warhol is the ideal artist, and NFTs are the ideal medium to re-introduce his pioneering digital artworks,” Noah Davis, a Christie’s specialist in postwar and contemporary art, said in a statement.

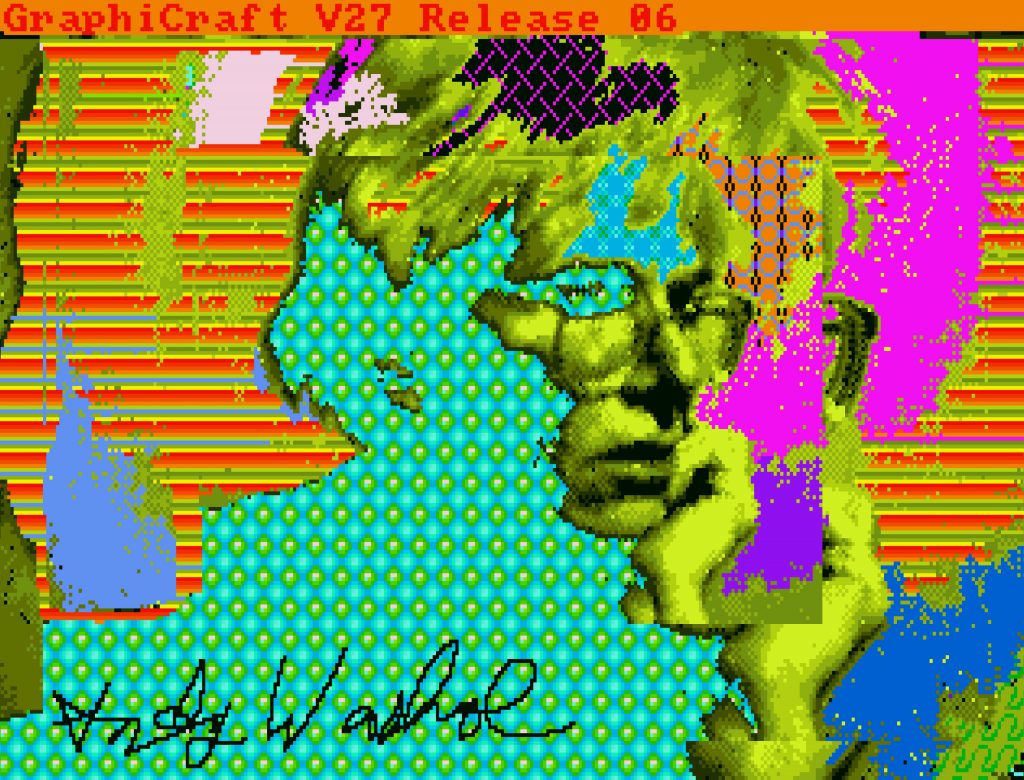

Andy Warhol, Untitled (Campbell’s Soup Can) (ca. 1985k, minted as an NFT in 2021).

©The Andy Warhol Foundation.

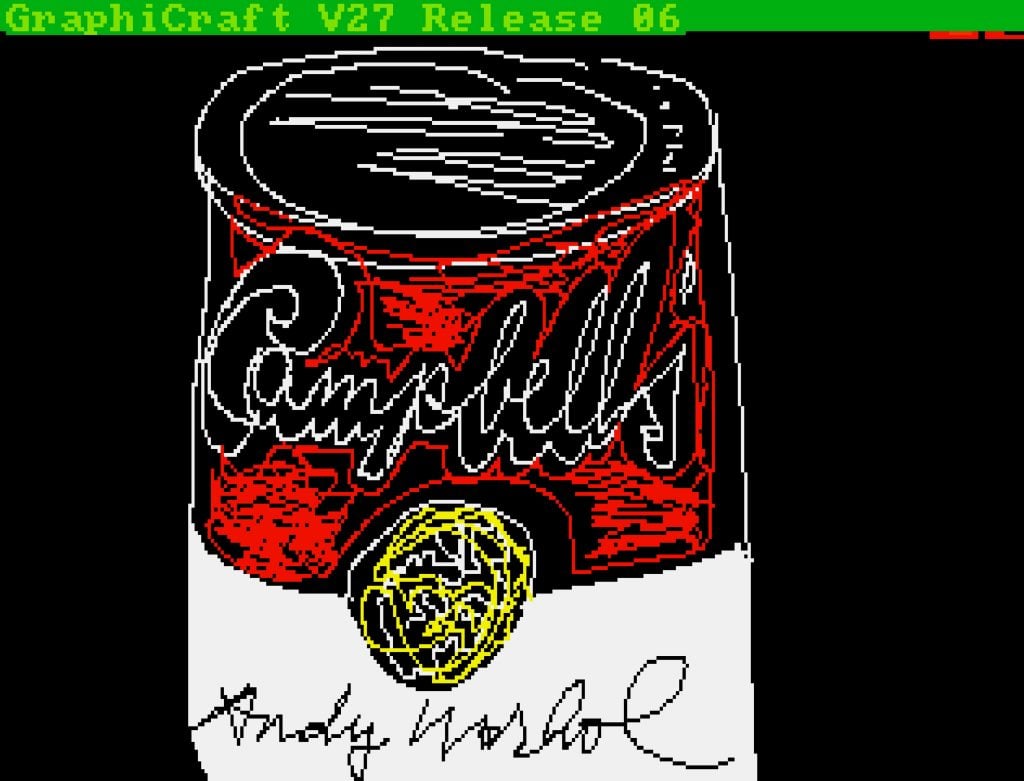

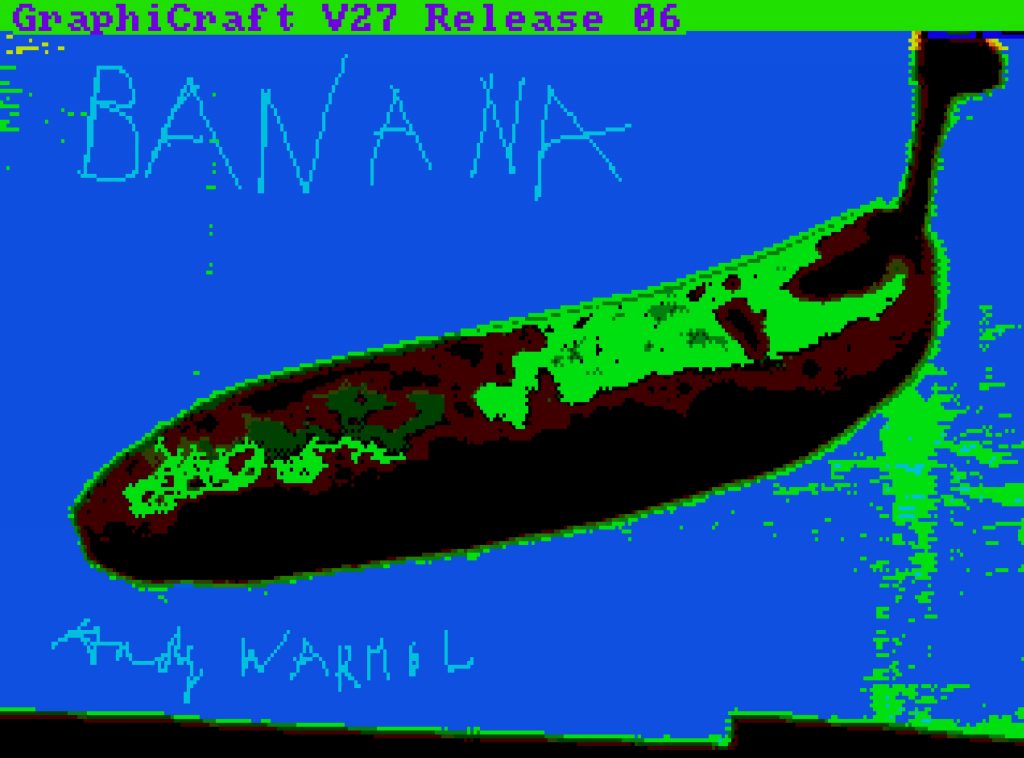

The auction, which is currently running from May 19 to May 27, is set to benefit the Andy Warhol Foundation and its grant program, which has an annual budget of $15 million, including a new $2.6 million program introduced last year to support artists affected by the pandemic. The untitled artworks for sale include two self portraits and images of a banana, a flower, and a Campbell’s Soup can, collectively representing some of Warhol’s best-known imagery, in a previously all-but-unknown medium for artist.

But what, exactly, will the winning bidders receive?

Each lot is offering a 4,500-by-6,000 pixel TIF image (which, as an NFT, is delivered via a unique address on the blockchain). But the original files were digitally excavated from 1.4-megabyte floppy disks.

Andy Warhol, Untitled (Banana) (ca. 1985k, minted as an NFT in 2021).

©The Andy Warhol Foundation.

“Warhol produced his paintings or drawings on the Amiga computer. The biggest image you could make on these things was 320 pixels across, which was what he was working with,” Golan Levin, new media artist and professor of new media art at Carnegie Mellon, told Artnet News. “The Amiga 1000 was an everyday computer. It could not have possible made a 27 megabyte image.… That would have taken a $2 million computer!”

As the director of the university’s Studio for Creative Inquiry, Levin was part of the team that recovered the original Warhol images. He contends that the image files sold at Christie’s are a far cry from the artworks as the artist had made them.

“They not selling what I would consider to be the original works by Warhol,” he said. “If you go to these NFT sites, people are offering high-resolution images because people expect high quality equals high resolution. It would have provoked such interesting conversations for Christie’s to actually offer the low-resolution original Warhols.”

Of course, it’s impossible to access the original digital file in the format that Warhol used in its creation. Commodore gave the artist an early Amiga prototype in the hopes of drumming up interest in the home computer. (Arcangel first learned about Warhol’s digital experiments via a YouTube video of an Amiga launch event where he created a portrait of Debbie Harry in front of an audience.)

Thanks to their retrocomputing expertise, the Computer Club was able to determine that Warhol saved the artworks in a prerelease version of an undocumented format called .pic.

“That was because Warhol had such an early version of the computer—they literally gave him serial number two or something like that,” Levin said.

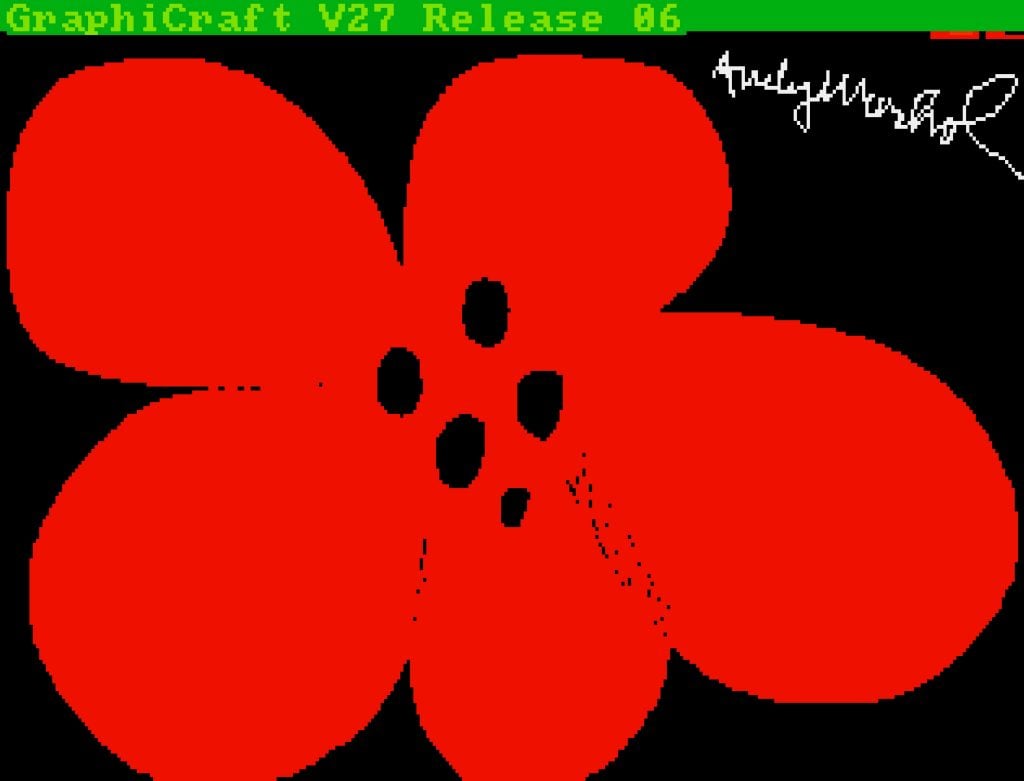

Andy Warhol, Untitled (Flower) (ca. 1985k, minted as an NFT in 2021).

©The Andy Warhol Foundation.

To read those images today, the Computer Club converted the files first to PPM, or portable pixmap format, and then to the modern PNG format. But the 320 by 200 pixel images that emerged looked short and squat, as if they had been stretched horizontally.

The Amiga, it turns out, used a non-square pixel aspect ratio, in order to account for the way the images would appear on the monitors of the era.

“When you would display these on a cathode-ray tube television, it would then look fine,” Levin said, noting that the Studio for Creative Inquiry actually did just that with the original resolution works in a 2019 exhibition, thanks to a loan from the Warhol Museum. (The museum displayed the works using a modern computer in the shell of an Amiga during its “Warhol and the Amiga” show, which ended in 2019.)

Recreation of Andy Warhol’s Amiga 1000 displaying one of the digital self portraits he made using the computer. Photo courtesy the Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh.

To approximate the image as it would have been seen by Warhol, the Computer Club attempted to correct the aspect ratio. They also created upscaled 24,000 by 18,000 pixel versions that could be used for print or exhibition purposes, according to a report from the Studio for Creative Inquiry. (Levin says this was at the Warhol Museum’s request.)

The resulting image “is not just arbitrarily scaled up in size. It’s actually stretched. The folks at the Computer Club applied a 20 percent vertical stretch that they eyeballed themselves—a bunch of grad students in engineering—so that pixels would look more square,” Levin said. “They also used an unsharp filter to improve the quality of the upscaled images.”

An untitled Andy Warhol self portrait displayed in its original size on an Amiga monitor at “Intersections,” the 30th anniversary exhibition at the Frank-Ratchye Studio for Creative Inquiry at Carnegie Mellon, Pittsburgh, in 2019. Photo courtesy of the Frank-Ratchye Studio for Creative Inquiry.

“At what point it is no longer the original file?” he asked. “If Christie’s were incredibly orthodox about it, they would actually be offering the unreadable Amiga file—you’ll get the hash of the Amiga file, and you’ll get a PNG of the original image so you can see what it looks like, and you’ll get a high resolution version that you can use as an exhibition copy, and we’ll throw in an Amiga monitor so you can display it exactly the way that Warhol would have seen it.”

The Warhol Foundation denies that it asked the Computer Club to create high resolution exhibition copies of the artworks, and argues that by its very nature, an NFT sale cannot offer the original file. (Technically, the NFT is a cryptographic hash of a signature on a blockchain that establishes ownership of a file that’s stored on a server.)

“The original drawings are not for sale; each of the five NFTs points to a restored and preserved file, which retains all of the artistry of Warhol’s Amiga compositions in a digital file format that can be accessed by modern computers,” Michael Dayton Hermann, the foundation’s director of licensing, marketing, and sales, told Artnet News.

Andy Warhol, Untitled (Self-Portrait) (ca. 1985k, minted as an NFT in 2021).

©The Andy Warhol Foundation.

“The NFTs offered for sale do not point to a physical floppy disc, but instead to the best representation of Warhol’s digital works,” he added. “Not unlike physical artworks that undergo careful conservation, the works Warhol created have been carefully preserved for posterity.”

Levin disagrees. “Christie’s really bungled it badly and indicated that they profoundly lack expertise in digital media,” he said. “It’s embarrassing and it insults the people who work in my field.”

UPDATE, 5/24/2021: The Warhol Foundation provided the following statement: “There is no question of authorship in this matter and to suggest otherwise is irresponsible and wrong. This is an intellectual difference of opinion about which file size and format is more appropriate for minting an NFT—an unreadable file on an inaccessible, deteriorating floppy disk, or a restored and preserved file. As the guardian of Warhol’s legacy, the Warhol Foundation is empowered to choose the format most suitable for minting these five NFTs. In making our decision to use tif files, we were guided by Warhol’s artistic intention for these pioneering digital works and our goal that they be preserved in a format to be enjoyed in posterity.”