Art Fairs

In a Climate of Political Uncertainty, Collectors Look for Safe Investments at ARCO Madrid

Amid political instability, collectors are buying less provocative works.

Amid political instability, collectors are buying less provocative works.

Hili Perlson

A provocative sculpture of King Felipe VI of Spain guaranteed that the 38th edition of ARCO Madrid opened with a bang this week—especially as the king, accompanied by Queen Letizia, was among the invited guests.

Spain’s leading art fair takes place exactly two months ahead of snap elections called by the country’s minority Socialist government after failing to get its budget through Parliament. Political tensions are running high, not least because the trial of Catalan independence leaders has finally begun. Last year, pixelated portraits by Santiago Sierra of the imprisoned politicians were censored by ARCO.

At the fair this year, King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia managed to steer clear of any potentially awkward encounters with Sierra’s latest work, which he made with Eugenio Merino: a hyperrealistic, 4-meter-tall “inflammable” sculpture of His Majesty. The buyer is obliged to burn the wood-and-wax giant within one year of purchase, and to film the process. After incinerating the sculpture, the collector will be left with a skull.

At the time of writing, the headline-grabbing work— which is priced at €200,000 and is titled Ninot after Spain’s satirical carnival sculptures that are burned at the end of a fiesta—was still awaiting a collector at the Prometeo Gallery booth.

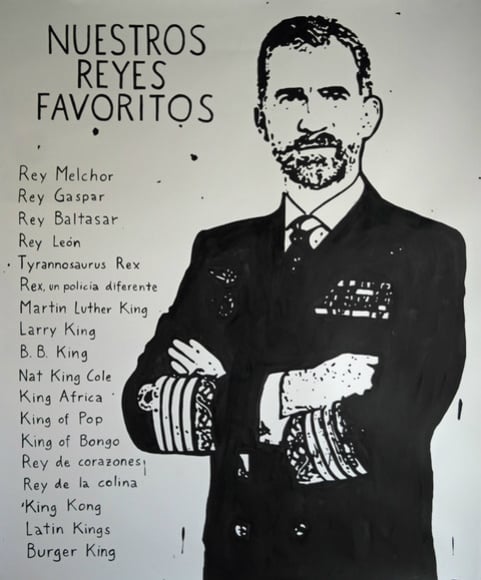

Another work at the fair that also featured King Felipe VI sold promptly, however. The painting, by the Finnish artist Riiko Sakkinen at Galerie Forsblom’s stand, is part of Sakkinen’s humorous takes on popular culture and language, a style he named “Turbo Realism.”

Riiko Sakkinen, Neustros Reyes Favoritos (2016-2019). Courtesy of Galerie Forsblom.

Titled Nuestros Reyes Favoritos (our favorite kings) (2016–19), it lists names of famous “kings”—Larry King, Nat King Cole, Martin Luther King—and brands (Burger King) next to a black-and-white portrait of the Spanish monarch. The work sold to the Spanish advertising magnate Luis Bassat, who was delighted to talk to the media about his €11,000 purchase.

But media frenzies aside, exhibitors who spoke to artnet News during the fair’s two preview days revealed that sales were generally healthy at modest price points, and collectors did not seem to be fazed by the country’s political turmoil. The Austrian gallery Rosemarie Schwarzwälder reported sales in the first three hours of the first preview day, ranging from €4,000 for a work on paper by Alice Attie to about €115,000 for an Imi Knobel.

“The atmosphere this year is buoyant rather than uncertain,” said Iwan Wirth of Hauser & Wirth. The gallery is showing a solo booth by Jenny Holzer, including new watercolors based on recently declassified US government documents that, although heavily redacted, reveal attempts to circumvent the Geneva Convention’s rules on torture. The works are going to the Guggenheim Bilbao, where a major exhibition by Holzer opens on March 22, so buyers of these items (several sold on day one) have to agree to loan them to the museum until September.

“The fair has a loyal following,” Wirth said. “We’re seeing Spanish collectors with whom the gallery has longstanding relationships, curators from across Europe, and the very welcome presence of collectors from Latin America, in particular from Peru and Venezuela.”

With Spain’s political drama, the ongoing crisis in Venezuela, and Brexit uncertainty, collectors are looking for relatively stable investments. So dealers are taking fewer risks, and one of the “safe bets” this year seemed to be Fernando Bryce. The Peruvian artist’s ink-on-paper works, which are based on reproductions of newspapers and magazine covers, were offered by at least four galleries, local and international. There are more of his works at the special booth of the Spanish newspaper El País.

Bryce looks at archival media coverage of historical events that shape our current reality. His diptych Apollo11/Luna15 (2019), for example, on view at Alexander and Bonin and priced €35,000, juxtaposes images of the moon landing with those of the the Allende Meteorite crashing into the Mexican Sonoran Desert.

The gallery also brought a photographic diptych by Willie Doherty, whose hometown of Derry in Northern Ireland (also known as Londonderry) could, in the wake of Brexit, once again become a city on a “hard” border separating the country from the Republic of Ireland.

The Madrid gallery Helga de Alvear dedicated its booth to German artist Julian Rosefeldt, showing photographic outtakes from his much-toured film installation Manifesto (2015). Alongside large-scale portraits of the actress Cate Blanchett as different characters, the booth also features a new body of work based on the iconography of equestrian monuments. Decorative saddlecloths are embroidered with passages from the Italian Constitution, one of many European countries where politics are increasingly polarized. The artist also published a text explaining the political subtext of the work, making sure that no one lured by the beauty of the fabrics misses the context.

Installation of Jenny Holzer’s work at Hauser & Wirth’s booth, ARCO Madrid 2019. © Jenny Holzer. All rights reserved DACS, London/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

That many dealers opted for subtly political works rather than in-your-face statements could also have to do with the general taste of Spanish and South American collectors. “They’re interested in abstract and conceptual art,” said Monika Branicka of the Berlin-based gallery Zak|Branicka, which has been showing at the fair for almost a decade. “They’re serious and take their time,” she added.

But the London-based curator Rafael Barber Ortell had a different take: “Lots of paintings mean that people are scared.”

He curated a presentation for Rosa Santos gallery of multimedia works by Chiara Fumai, the Italian artist who died in 2017. (Fumai’s work will be included in the Italian Pavilion in Venice this year.) The presentation includes works from her “Madonna Horeinte” series, a biting, furious reaction to a written request by a Christian organization to portray a feminist image of the Virgin Mary.

Fumai was known for her intense feminist performances, in which she would channel historical and mythological women who were oppressed by the patriarchy. “The burden of her work became too much,” Ortell said.

The work has garnered interest from Spanish institutions, but had not yet sold at the time of this writing. In light of the wave of anti-abortion rhetoric by some right-wing politicians in Spain, radical feminist art may still be too risky for some.