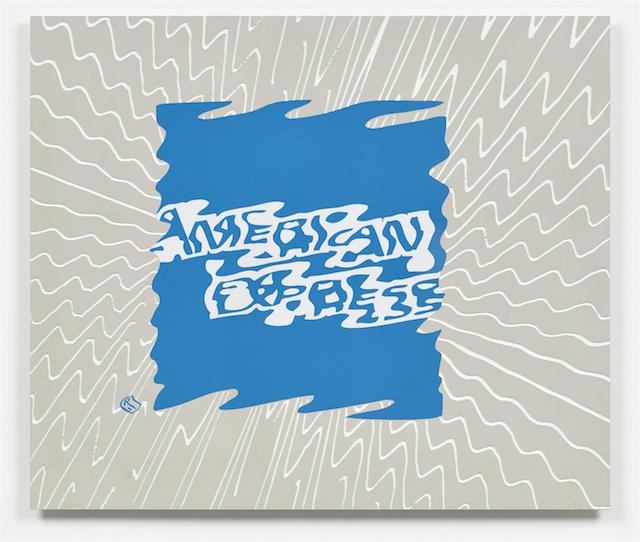

Courtesy Max Hetzler.

People in the art world joke that if you want to sell works at an art fair, just bring your biggest, shiniest objects. They’re attractive, and they’re selfie bait to boot, so they circulate well on social media.

The big and shiny coexist with the socially and politically pointed at this year’s Art Basel in Miami Beach, where 267 dealers converge with tens of thousands of art lovers each December.

Among them at Wednesday’s VIP preview were big shots like Thomas Campbell, director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tate trustee Richard Chang, megacollector Eli Broad, movie star collector Leonardo Di Caprio, baseballer Alex Rodriguez, and even Sylvester Stallone.

Sales were strong, multiple dealers reported in the opening hours. “I already have to update myself on what we’ve sold so far,” David Zwirner director Hanna Schouwink told artnet News—this about an hour into the VIP preview, which started at 11 a.m. The mood is “more than robust,” New York dealer Friedrich Petzel said a few hours later.

It’s always nice when the consumerism that fuels the art fair machine is capably commented on by a bright and shiny artwork, so I was very pleased to find Raymond Hains’s painted bronze work based on a distorted version of the American Express logo, on offer from Berlin’s Max Hetzler Gallery and priced at $88,000.

Jeppe Hein, You Are Amazing Just the Way You Are (2015)

Image: Courtesy http://www.jeppehein.net/

An hour or so into the preview, New York’s 303 Gallery had sold two of Jeppe Hein’s square, wall-hung sculptures with neon reading “You are amazing just the way you are” against a gray background, for about $42,500 each. The work neatly emblematizes the affirmation we seek in retail therapy.

Chris Martin, Untitled (2015).

Courtesy Anton Kern, New York.

Glitter was on the scene in more than one place, with Kim Gordon’s paintings incorporating the stuff at 303, as well as Chris Martin’s efforts nearby at Anton Kern.

“If you told me you knew a great painter who worked with glitter, I’d say forget about it,” the gallery’s Christoph Gerozissis told me. But Martin makes it work, with intense, dark colors in horizontal bands recalling an evening landscape overlaid with the shiny dust.

Brian Calvin at Anton Kern.

Photo: Brian Boucher.

Kern also has a great Brian Calvin painting of an androgynous youth that I was sure was a girl and Gerozissis felt confident was a boy. Regardless of the subject’s gender but in view of the work’s sex appeal, he said, “You actually want to have sex with the painting.”

Anish Kapoor, Like an Ear (2014).

© Anish Kapoor, courtesy Lisson Gallery.

At London’s Lisson Gallery, an Anish Kapoor sculpture carved out of onyx also offered a lush visual appearance, but with uncanny undertones.

The giant pink object, Like an Ear (2014), lies on the floor and takes roughly the shape of a human tongue, but with a weird aperture near its back. The material, according to director Alex Logsdail, comes only from quarries in northern Afghanistan, tying the generation of luxury objects with one of the world’s poorest and most war-torn regions.

Jimmie Durham, Mestre Surely Was Intended to Bring Development to the Lagoon of Venice (2015).

Image: Courtesy of Brian Boucher.

Also injecting a darker mood into a gleaming object is Jimmie Durham, at Mexico City’s Kurimanzutto. Mestre Surely Was Intended to Bring Development to the Lagoon of Venice (2015) consists of a chunk of Murano glass sitting atop an iridescent purple oil can, an unsubtle reference to global conflict and the environmental destruction wrought by fossil fuels.

In a statement provided by the gallery, Durham writes, “In the ’20s, Walter Benjamin wrote that the sign of modernity was the rainbow, iridescent colors of an oily surface in a puddle of water on a city street on a rainy night. All of our poisons are so filled with our hopes and efforts.” Durham, a Cherokee, has notably exiled himself from the US, now making his home in Berlin.

Dark realities outside the fair asserted themselves partway through the preview, with news of a mass shooting in San Bernardino, California, popping up on my phone. The night before, Rashaad Newsome had led a parade of black marching bands, dirt bike riders, and voguers through the streets of Miami, led by a “Black Lives Matter” sign, alluding to the continuing struggle for civil rights in America.

Alfredo Jaar, Mississippi Goddam, at Kamel Mennour.

Photo Brian Boucher.

Racial conflict shows up explicitly at the fair in the form of Alfredo Jaar’s work Mississippi Goddam, on view at Paris’s Kamel Mennour, which refers to a 1962 Nina Simone song about African-Americans’ struggle for civil rights. A wall-hung print shows the song’s title, followed by repetitions of the title with the state’s name blanked out, to be filled in with the name of other sites of outrage (Ferguson, Chicago, etc.). Felix Gonzalez Torres-style, a stack of posters with the same image rests on the floor in front of it.

Wilson Díaz, Amarillismo—Composición I (2015).

Photo Brian Boucher.

Also tying conflict to music, strangely enough, is an installation at Bogotá’s Instituto de Vision, in the fair’s “Nova” section, for younger galleries. (Instituto de Vision is just two years old.)

Wilson Díaz’s Amarillismo—Composición I (2015) consists of several shelves supporting the jackets of a few dozen vinyl records the Colombian artist has collected over the last seven years. Some show the singers adopting the pose of guerrilla fighters; others are musical releases by actual guerrilla icons; yet another shows a singer pretending to be a policeman. There are also recordings of politicians’ speeches.

Díaz’s sculpture was one of the last things I saw Wednesday, after a marathon of plodding from booth to booth, trying to make sense of the juxtaposition of luxury items and artists’ attraction to more difficult subjects. Few things could have brought it all together better than the way the records combine both officials’ and rebels’ messages in the artistic expression of the LP vinyl record.