The Art Detective

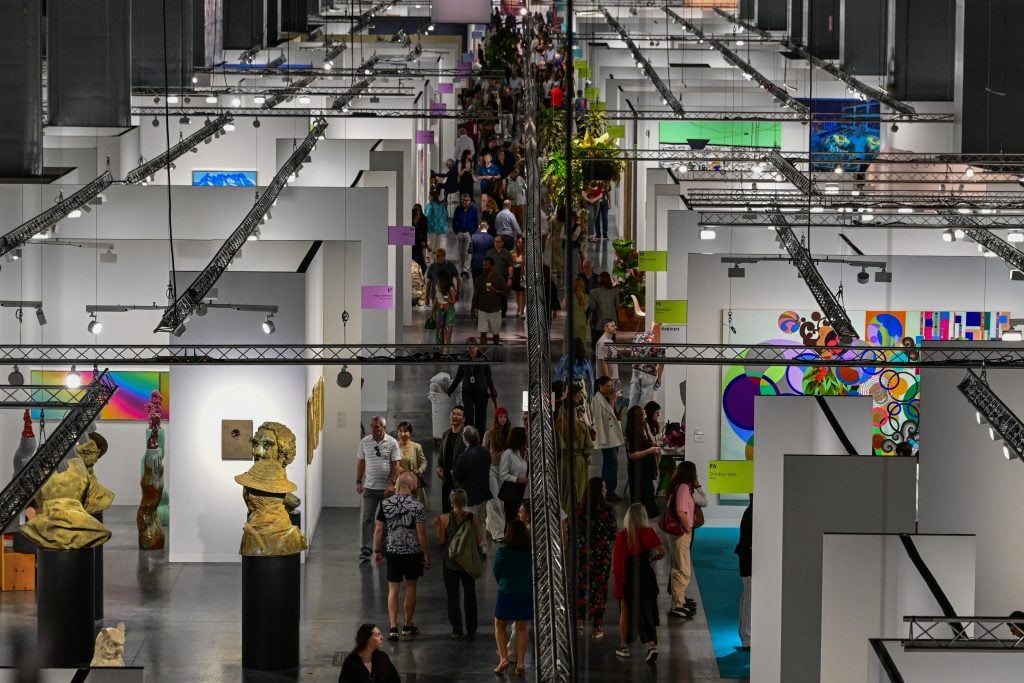

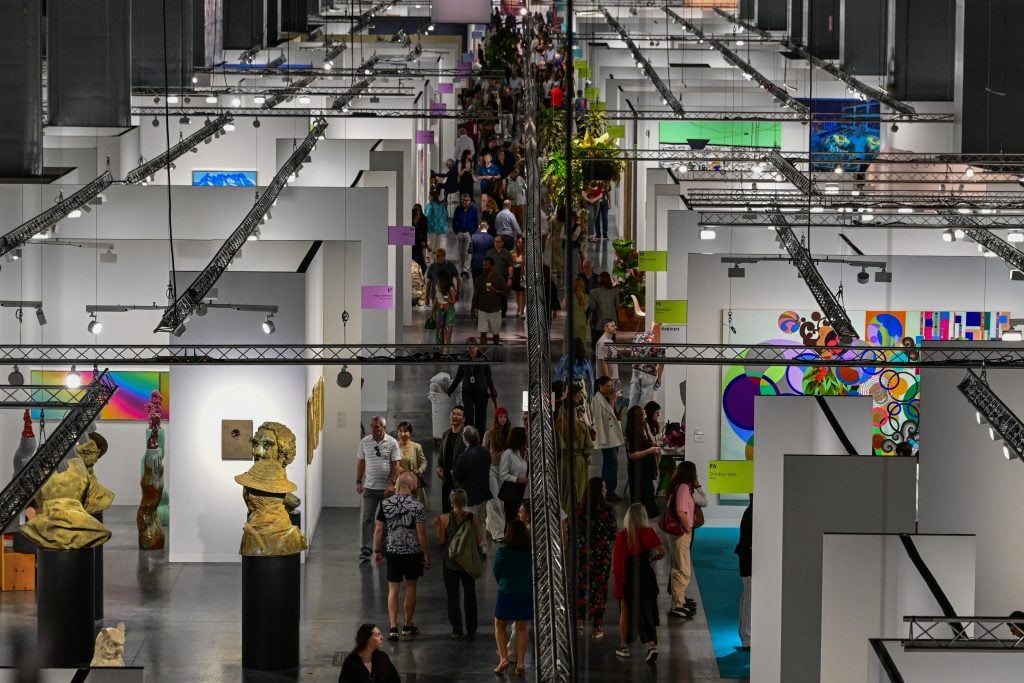

Not Desperate, Not Euphoric: At Art Basel Miami Beach, Dealers Adjust Their Expectations—and Expenditures

One sign of the times: The consignor of a $27 million Gerhard Richter may be prepared to take a loss.

One sign of the times: The consignor of a $27 million Gerhard Richter may be prepared to take a loss.

Katya Kazakina

Palm trees, ocean breezes, interminable traffic across Biscayne Bay, big-dollar deals, and parties are all staples of Art Basel Miami Beach. This year, the traffic seemed a lot more intense; the parties and deals, not so much.

Suffice it to say that the international, highly respected gallery Sprüth Magers didn’t sell a thing on the fair’s second day, after reporting nine sales on day one. Senior director Andreas Gegner shared that with me Thursday evening on the 14th-floor terrace of the still-fashionable Soho Beach House in Mid-Beach, which overlooks the tent where White Cube used to throw its famous annual party. It seemed quiet down there, like nothing was going on.

I was happy to make it to Soho House after an hour-long, bumper-to-bumper taxi ride. It was just past 7 p.m. when I got there, and I braced for a long wait to enter, but—gasp!—there were no lines. I breezed through. Cecconi’s restaurant and pool were eerily empty. Where was everyone?

Artist Tracey Emin, in red, at the British Council party in Miami. Photo Katya Kazakina

Puzzled, I proceeded upstairs, where London collectors Paul Ettlinger and Raimund Berthold hosted a lively gathering to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the British Council, an international organization for cultural relations. Prosecco was poured into crystal goblets. Tracey Emin looked resplendent in a red dress. The chatter among dealers, who included Sadie Coles, was that the fair has not been a roaring success, despite a stream of reported sales.

“It was good enough not to be desperate, but not good enough to be euphoric,” Gegner said. The gallery pre-sold more expensive works, including John Baldessari’s Vertical Series: Fun (2003), a photographic print on foam PVC board, for $325,000 and Richard Artschwager’s charming 2001 sculpture in the shape of a bristly yellow exclamation point for $425,000. Several lower-value works sold at the booth.

Collectors Paul Ettlinger, right, and Raimund Berthold at their party for the British Council during Art Basel Miami Beach. Photo: Katya Kazakina

The fair’s results will take some time to shake out.

“Way too often collectors cancel sales flippantly,” said Marc Spiegler, Art Basel’s former global director, who was recently elected president of Superblue’s board. “They pay way too slow.” Meanwhile, galleries have to pay steep upfront costs, like rent, payroll, and exhibition buildouts. “It’s the perfect storm,” Spiegler said.

PARTIES

Perhaps these kind of calculations dampened the party scene this year. White Cube canceled its annual rager on the beach (instead hosting a dinner for Marguerite Humeau to celebrate her solo show at the ICA Miami). David Zwirner and Hauser and Wirth held a joint event at Casa Tua (“That’s… friendly,” a prominent art adviser said.) Pace said it wasn’t doing a party this time.

It’s been a year of belt-tightening in the art market, and extravagant parties, of course, are an easy expense to cut.

“White Cube 100 percent is re-assessing what’s the best use of their money,” said collector and investor Max Dolgicer, who told me about a banker friend who religiously came to Art Basel Miami Beach for more than two decades. This year, he skipped it.

“I asked him, ‘Why are you not going?’ He said, ‘Last year I entertained 60 people. It cost me a fortune. I started to do smaller dinners. For half of the cost, I can have three dinners in New York.”

To be fair, Perrotin threw a bash at the Edition hotel with a pop-up by the Paris club Silencio. It was a mob scene, with $40 cocktails and strobe lights. Gagosian took over Mr. Chow for its traditional mega-dinner. One guest, adviser and collector Ralph DeLuca, described it as “mix of heavy hitters in the art world and would-be posers.”

“We went from a market where outside people were begging for access to art to now begging for access to dinners and parties,” DeLuca said.

A dancer at the Tolga party during Art Basel Miami Beach in 2023. Photo: Katya Kazakina

Another staple of art fair circuit, pop-up banger organized around the corner from the Bass museum by party promoter Tolga Albayrak got shut down soon after midnight, with rumored causes ranging from underage drinking to a bomb threat.

“I don’t know the real reason,” Albayrak said in a text message. “It’s probably due to the permits, because they opened just the night before, but nothing major like that.”

DEALS

What’s the deal with the $10 million Warhol at Gagosian? Yet unsold, the large-scale 1963 painting Ethel Scull—seven feet tall and 11 feet wide—depicts several different portraits of art collector Ethel Scull on a silver background. The silkscreen is among the most expensive artworks at the fair. And yet, the asking price strikes me as low.

Warhols from that year have sold for considerably more. Take the much larger Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster), which fetched $105.4 million in 2013. Or White Disaster [White Car Crash 19 Times] bought by Peter Brant for $85.3 million in 2022. Or the triple, double, and single Elvis Presley paintings that have gone for between $37 million to $81.9 million. Even Silver Liz (Diptych) fetched $28 million in 2015.

Andy Warhol’s Ethel Scull (1963) at Gagosian’s booth at Art Basel Miami Beach 2024. Photo: Katya Kazakina

Ethel Scull is known to have been owned by the Mugrabi family, who very publicly bought Brant’s Basquiat work on paper for $23 million at Christie’s last month. Are these two transactions related? (I reached out to Alberto Mugrabi for comment, but he didn’t respond).

“It’s priced to sell,” a prominent international art adviser said of the painting. “Ethel Scull is not famous. She is a socialite more than a celebrity.”

For older generations, Ethel and Robert Scull were household names, foundational to the development of today’s market for contemporary art. The 1973 auction of works from their collection at Sotheby Parke Bernet was a watershed moment. But do younger buyers know who Ethel Scull was? Does her name matter to them? It’s not Elizabeth Taylor or Marilyn Monroe.

Warhol’s celebrity subjects don’t resonate as much with younger buyers, a private dealer told me. “Flowers do, and maybe dollar signs,” he said.

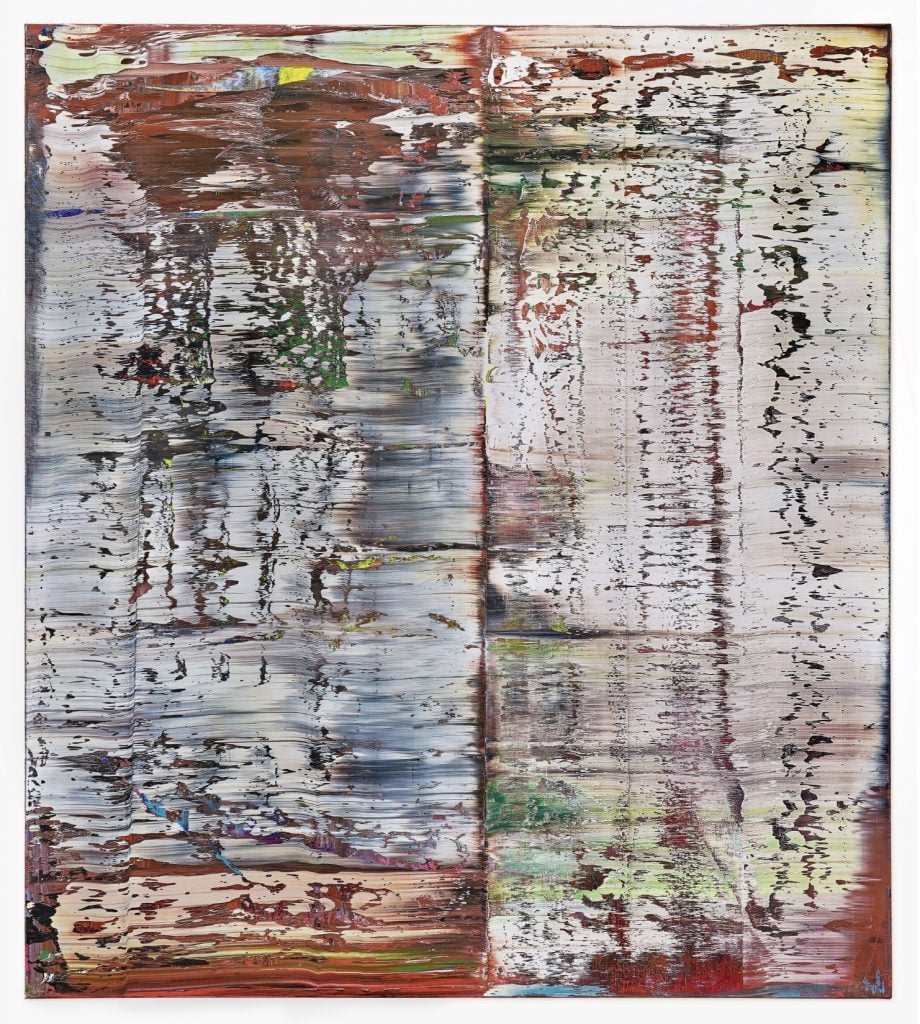

Gerhard Richter, Abstraktes Bild (1990). Courtesy: Helly Nahmad Gallery

Another painting intrigued me: Gerhard Richter’s Abstraktes Bild (1990), priced at $27 million by the Helly Nahmad Gallery. Again, this is one of the top prices at the fair—and yet it’s little changed from just two years ago when it fetched $25.5 million at Sothebys Hong Kong.

The exhibition history published by the auction house suggested that it was being sold by Taiwanese billionaire Pierre Chen. (It was part of “Guess What? Hardcore Contemporary Art’s Truly a World Treasure: Selected Works from the Yageo Foundation Collection” at the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, Japan, in 2014.) Chen had acquired the work for $11.6 million at auction in 2011, according to the Artnet Price Database.

The identity of the Richter buyer in Hong Kong is a mystery. The work was guaranteed and backed by an irrevocable bid. Did the guarantor get stuck with it? The painting returned to the market after the 2022 auction, according to a private dealer who had been told that the owner wanted “to get out.” It seems that the person was prepared to take a loss.

Will the gallery manage to offload the painting? Art Basel Miami Beach runs through Sunday.

Art Basel Miami Beach is on view at the Miami Beach Convention Center, 1901 Convention Center Drive, Miami Beach, Florida, December 4–8, 2024.