Market

Art Demystified: How to Authenticate a Contemporary Artwork

Everything you need to know about authentication.

Everything you need to know about authentication.

Henri Neuendorf

Authenticity is one of the most important properties of an artwork. After all nobody—in most cases—wants to buy a fake. However when the stakes are high, the process of authentication can be complicated, and fraught with difficulties—especially when the artist is dead.

And in the contemporary art market authentication of high-priced works has become contentious.

“You take a chance,” Richard Polsky, of Richard Polsky Art Authentication told artnet News. “The risk is that when a collector or dealer submits something and they’re wrong, not only are they going to lose money on the deal they’re working on involving that piece, they risk their reputation too.”

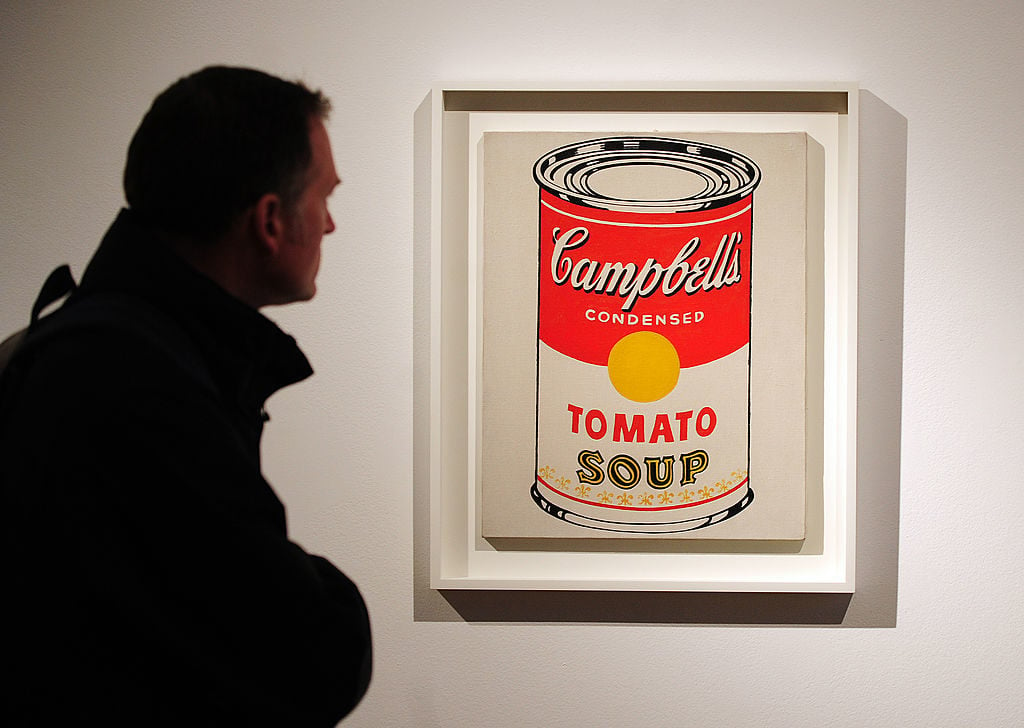

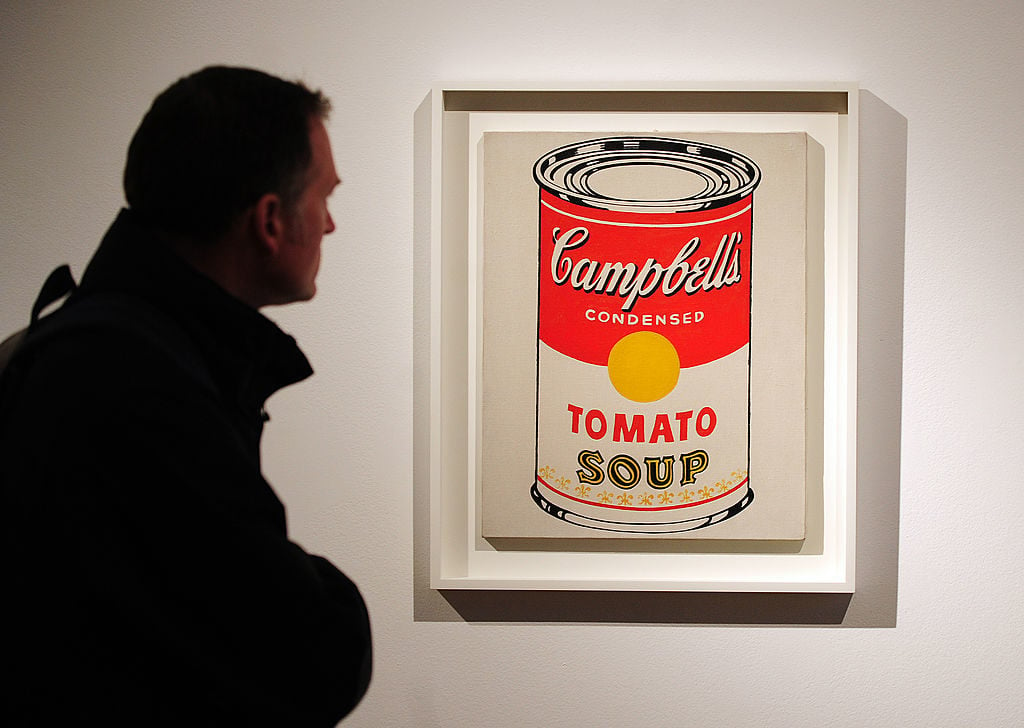

For example, “If you gave your painting to the Warhol people,” he explains, “if it was rejected, they would take a rubber stamp, and stamp the word ‘denied’ on the back of it. Then you were really out of luck, because you signed a piece of paper agreeing that they had permission to do that.”

The problem is that some wealthy collectors aren’t prepared to take no for an answer. Over time, they started taking artists’ foundations to court over their decisions, prompting many foundations, such as the Warhol Foundation, the Basquiat estate, and the Haring Foundation to cease offering the service.

“They’ve all been very frustrated over the years by lawsuits,” Polsky said. “The Warhol Foundation probably put it best when they said, ‘we want to spend money on art and artists, rather than on lawyers.’”

The authenticator explained that respecting the artist’s intent is key. “The problem is once an artist dies, of course there’s no way of going back and asking ‘did you make this? There’s nowhere to go with it. So an authenticator like myself then has to make the decision. Is this what the artist wanted to represent him? Or did he do it for other reasons?”

To illustrate his point, Polsky recalls an anecdote featuring Willem de Kooning, “the great painter lived out in the Hamptons,” he says. “There was a wooden outhouse with a wooden toilet seat on the property, and one day he went out there, and he painted it. And years later some art dealer somehow got a hold of this and tried to sell it as a de Kooning, when you and I both know de Kooning didn’t intend for that to be one of his paintings, he was just having fun.”

Polsky concludes, with resignation, “This is what happens in the art market—crazy things.”