Thanks to multi-billion-dollar November art auctions in New York and the ever-growing behemoth that is Art Basel in Miami Beach each December (with an estimated $3 billion worth of art on view), the tail end of the calendar year has become one of the busiest for the global art trade.

This frenzy of buying and selling between dealers, auction houses, and collectors, translates into an equally dizzying routine with regard to art shipping—be it from auction houses to private homes, to freeports in Switzerland and Singapore, from residential collections loaning works to prestigious museum shows, and from art fair booths to the homes of eager buyers abroad.

So what could go wrong? Plenty.

“I would say that the majority of art losses occur while items are in transit,” says Laura Doyle, fine art specialist with Chubb Insurance.

artnet News spoke to Doyle and other experts on issues including insurance, shipping, and conservation to bring collectors the most crucial and up-to-the-moment tips about what they should do after they seal the deal on a major acquisition. There were cautionary tales galore of inexperienced art handlers, unwitting maintenance workers, or unsuccessful do-it-yourself-ers and their ensuing mishaps, which include permanently damaged paintings and one instance of a decapitated sculpture.

Here, then, are seven shipping nightmares and advice on how best to avoid them:

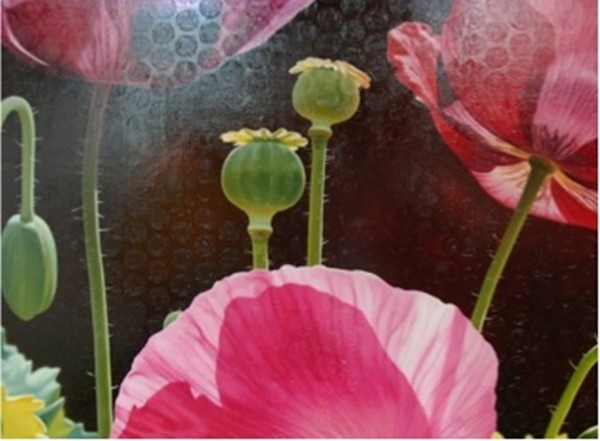

Detail of bubble-wrap marks on an improperly packed Old Master painting.

1. Don’t try this at home (AKA don’t do it yourself).

“We always encourage clients to work with professionals but sometimes they take things into their own hands,” said Doyle. “We’ve had a number of clients who have had damage when they try to rent a U-haul to transport things themselves or try to hang things themselves.” Doyle noted one client who rented a U-haul to transport marble sculptures and “didn’t have them properly packed. He had them standing up in the back of the U-haul and he had ropes holding them together. He wound up swerving on the highway and decapitating one of the sculptures.”

A bowl that was damaged in transit.

Image: Courtesy of AXA Art Insurance.

2. Vet the shipper

Make sure the shipper has expertise in handling art, said Doyle. “When we’re advising clients on how to ship an item we always suggest that the truck has GPS, climate control, a security system, proper suspension, as well as two drivers. And then if possible, the truck should always take a direct non-stop route.”

And even after you’ve vetted your shipper it’s important to be as specific as possible with the dimensions and weight of the work, advised Colin Quinn, vice president and director of claims management at AXA Art Americas. A case in point: A gallery that is an insured AXA client “enlisted the services of a fine art shipper to transport an installation from a lender’s home to the institution a considerable distance away. The dimensions of the installation were approximately 5 by 8 feet and weighing over 300 pounds, but for some inexplicable reason, the shipper only assigned two art handlers who attempted to load the work Laurel and Hardy style onto the waiting truck. Predictably, the work was dropped, causing significant damage, to the chagrin of the lender and institution.”

Lesson learned? “Be sure that the dimensions and weight are clearly relayed to the shipper and adequate art handlers are assigned to the task.”

3. Always get a condition report before the work ships and immediately after it arrives.

Another client mishap for one of Doyle’s insured art owners occurred when they hired general movers (i.e. non art specialist movers) to handle a 9th-century Indian sculpture of a Hindu god. “It was an elephant and they ended up picking it up by the trunk—which would have been the weakest point of the piece,” said Doyle. “The trunk broke off the face and they actually threw it away. So we couldn’t even try to to have the piece restored.” Doyle said, “We always tell clients to do a condition report before they have anything transported and then again to commission a report once the items are received. Just so they can see any changes.” Though we would politely point out we think that broken/missing elephant trunk would be pretty tough to miss!

4. Find out whether third party shippers or other subcontractors will be involved.

“It’s not unusual for art transporters to subcontract out jobs to third parties,” said Doyle. “So it’s important to understand if that’s going to happen and to make sure that that third party has the same standards and has background checks on all its employees. The company you’re hiring may not be doing the actual transit. That’s especially true if you’re going long distance or internationally when shippers specifically work with a network. You want to make sure that that sub-contractor party knows exactly how many crates they’re shipping because there have been instances where things have gone missing.”

5. Don’t assume that all parties will follow best practices just because you do.

“One of our insureds consigned a sculpture to a gallery and took great pains to oversee the packing and crating of the work prior to shipment,” recounted Quinn. “The sculpture was carefully fastened into the crate which was marked ‘fragile,’ with the top end clearly indicated. When the work was returned to the owner it was in a larger crate with the sculpture covered in bubble wrap and surrounded by Styrofoam packing peanuts. When the owner removed the bubble wrap it revealed the sculpture had broken into three pieces. When the owner complained to the gallery they explained that the original crate had been inadvertently discarded and they had to make do with the materials at hand. ” Quinn added, “It is important to convey shipping and return instructions to all parties entrusted with the artwork.”

6. Be careful with ephemeral materials

In our recent story about the “Five Riskiest Art Buys” we told you about artists such as Damien Hirst or Marc Quinn whose use of unorthodox or ephemeral materials can prove problematic from a conservation viewpoint. That also holds true for when such unusual works—think of Marc Quinn’s self portrait cast in the artist’s own blood, or Hirst’s shark immersed in formaldehyde—have to travel.

“The most common time for a work of art to be damaged is when it is being moved. Art is safest installed or stored in a safe place and left untouched,” says Miami-based Emily McDonald Korth, a conservator and founder and CEO of Art Preservation Index (APIx), a stability rating system for fine art. The term for it is “benign neglect,” she adds.

McDonald-Korth said that as much as she loves German artist Anselm Kiefer’s work, “his material choice is consistently problematic.” She recounted attending the opening of a recent show. “It was a massive installation of his which I was really looking forward to seeing. When I walked into the gallery, it was so impressive and gorgeous. As A got closer to the work, in some of these pieces there was measurable handfuls of materials sitting underneath the work, It wasn’t only a conservator that could see…it was obvious where the pieces were falling off…I assume that this happened during shipping and installation, and it happens a lot.”

McDonald-Korth’s advice? “Make sure you have a full-time person taking care of those things,” like maintenance, conservation and shipping for such fragile work. “It really is worth it. If you’re spending $75 million on a painting, you can afford that.”

In the same vein, Doyle says it’s crucial for handlers to understand the materials they are working with. Even something as innocuous-seeming as bubble wrap, when improperly used, can leave bubble imprints on a work (above). Not only do these permanently mark and damage a work, the bubble imprints can then trap moisture and lead to mold, notes Doyle.

7. There is no substitute for common sense when packing and shipping artwork.

Final words of wisdom from Colin Quinn, and a case study to go with it. An insured client agreed to ship a large installation from his location to a gallery a short distance away. The work was too large to fit through the elevator doors of the owner’s residence, so the art handlers enlisted the help of the building owners who instructed the art handlers to place the work on top of the freight elevator and the building super would manually lower the work to street level. “For reasons best known to the super he pushed the up button for the elevator and the work was crushed as it went to the top floor of the building.”