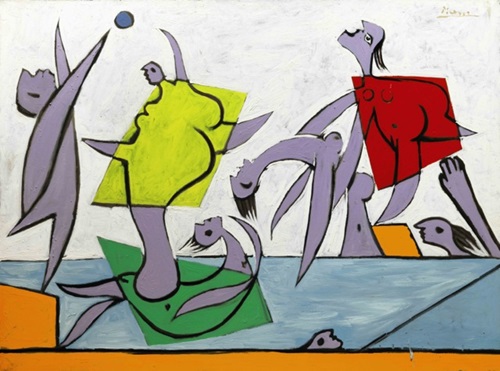

Pablo Picasso, Le Sauvetage, painted in November 1932, estimated to sell for $14 to $18 million

Photo: courtesy Sotheby’s.

A Letter to Dan Loeb Regarding Sotheby’s

Dearest Dan,

It is a truth universally acknowledged that anyone in the art world in possession of a good fortune and some business smarts thinks they can run an auction house. Or more accurately, thinks they can do it better than whomever is doing so at the time. They believe they can negotiate better contracts, cut more costs, appraise more accurately, marshal more nation’s treasures to the block.

Reality is a little more complicated.

Which brings us, of course, to you, dear Dan, with billions under management, an impressive art collection, a love of publicity and an unrequited longing it would seem to me for getting into the auction house management business. If not, then why else launch the proxy fight to bring your own slate of directors to the Sotheby’s board? It could be a prelude to greenmail, a type of lucrative fiscal blackmail in which a raider takes over a company, bashes it into better shape, and then sells his shares back to the firm at a profit. But no, perhaps you really want to own an auction house.

Wall Street folks frequently think their financial success can migrate to the art world, be it in an auction house, gallery or museum board. My experience, in years of reporting on first the Goldman Sachs’s & the Morgans, and then the auction houses, tells me the only person to do so successfully was Robert Mnuchin. On the other side of the ledger I have only two words: Alfred Taubman, a mall man who was also successful. Until he was jailed.

Having spent years in both cultures, they couldn’t be more dissimilar in rhythms, skill sets, corporate cultures. Wall Streeters are proud to do deals over lunch at laminate-wood tables. Strangely, mayonnaise is virtually always involved, as are bad manners and worse jokes. The art world is all good suits, French service, surface opulence hiding a frantic backstage. Vicious sibling rivalry rarely comes into play in IPOs, for example, but to auctioneers seeking estates, it’s a Tuesday.

Sotheby’s travel and expenses were $33 million in the most recent year. To outsiders, this may seem frivolous. It is not. It’s necessary to create the atmosphere of carelessness, in the old-fashioned, good sense of that word, that is, to induce people to buy the most luxurious of luxury goods.

So, why would you want to own a global luxury goods concern with paper-thin profit margins? And how will you improve those? No more shrimp the size of fists? Will that do the trick? You promise cost-cutting. You promise less sharing of commissions or upside with consigners—although the strategy landed Sotheby’s the Jackie O sale—but think it won’t impact market share. You also say you will “cultivate numerous points of contact within Sotheby’s so that art buyers become clients of the Company, not just the individual salesperson.”

And well, gee, no one’s ever thought of that before, right? Actually, madames have been trying that tack for centuries—but customers will always have their favorite trollops. And, yes, Sotheby’s board rubber-stamps decisions and that isn’t good, but are your guys really going to stand up to you? It’s poor form, as a reporter, to roll your eyes when someone speaks, but a decade or two in, you begin to feel sorry for the legion of would-be auction house kings and queens who for some reason think everyone that came before them had no idea what they were doing.

Sotheby’s is attempting to do all it can to dissuade you. The annual report is almost tabloid reading, given the menu of destruction it details. The risks section, usually routine and relatively small at public companies, is four pages. So, what, exactly, can go wrong at an auction house? Simply put: the economy, government laws, demand for art is unpredictable, intense competition, loss of key personnel, possible failure of existing business plans, reliance on a “small number of clients” for a significant contribution to revenues, borrower bankruptcy, changing value of assets, insurance costs, damage to items, people don’t pay, inability to control or predict sales volume, foreign currency movements. A lot can go wrong, in short.

The elephant-in-the-room of the “risks” disclosure is halfway down: “A small number of shareholders may ultimately impact Sotheby’s business.” That, at about a 16 percent stake, is you, dear Dan. Sotheby’s warns these shareholders “may be able to exert significant influence.”

That said, Sotheby’s needs something. Comfortably ahead of Christie’s in market share for centuries, then neck and neck for the last decade, it is now circling 47 percent. Being private has been a strategic advance for Christie’s: more maneuverability and less oversight of its deals. It’s also been far better at online sales and more cutthroat in general, scheduling, as just one example, an upcoming sale directly against Phillips. Sotheby’s biggest seismic shift lately has been to hire a design firm to re-brand itself; the new look and logo typeface was debuted earlier this month. (Serif! Sans serif! Who can keep track?).

There’s also been a spate of insider stock sales disclosed to the SEC. Not a troubling amount, but a noticeable one.

The company appears to be placing most of its 21st century chips on a joint auction venture with the government of China, a nation Sotheby’s features in its marketing material more often than Kim Kardashian makes People. But even the auctioneer admits how big that hurdle is.

So, think this looks easy? Mr. Loeb, here’s my artnet office number: 212-497-9700, extension 212. I’m available any time.

A.P.