Art Fairs

What Can an Art Fair Offer Amid Political Instability? For Dealers at This Year’s ARTBO, the Answer Is Complicated

The Venezuelan crisis is having a marked effect on Bogotá's art market.

The Venezuelan crisis is having a marked effect on Bogotá's art market.

Rachel Corbett

The 14th edition of ARTBO, Colombia’s premier art fair and one of the leading market events on the Latin American calendar, opened this week amid a period of dramatic change in the country. Last year, a historic peace deal in Colombia ended a half-century of civil war. But now the nation is entering yet another fragile phase with the election this past summer of conservative president Iván Duque, who has vowed to roll back the peace agreement.

It remains to be seen how Duque’s policies will affect the country’s burgeoning art scene, but he personally boosted ARTBO on Thursday with an appearance at the fair, which is funded by the city’s Chamber of Commerce. “ARTBO has become the most important South American fair for modern art,” he said at a press conference at the Corferias convention center. Culture has the power to “unite Colombians” and to become “the great antidote to violence,” he added.

Each year, dealers and artists contend that the fair is increasingly breaking out of its regional status to rival Latin American heavyweights such as Mexico City’s Zona Maco. But although its profile is undoubtedly rising, the opening VIP preview felt a bit sparse, with some dealers predicting that most sales would happen on the final days.

Some exceptions included a text work by Beto Shwafaty about colonialism and the sugar trade at Galeria Luisa Strina’s booth, which the Museum of Modern Art Medellín had placed on hold with a pricetag of $25,000. Several sales had also been made at the Venezuelan gallery Abra, which reported selling two works by the indigenous Yanomami artist Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë (priced between $2,500 and $7,000), as well as works by the late artist Pedro Terán, one of Venezuela’s leading conceptualists, which were going for upwards of $12,000.

Beto Shwafaty, Sugar in the Veins Sugar Blues) (2017-18) at Galeria Luisa Strina, ARTBO, Bogotá, Colombia.

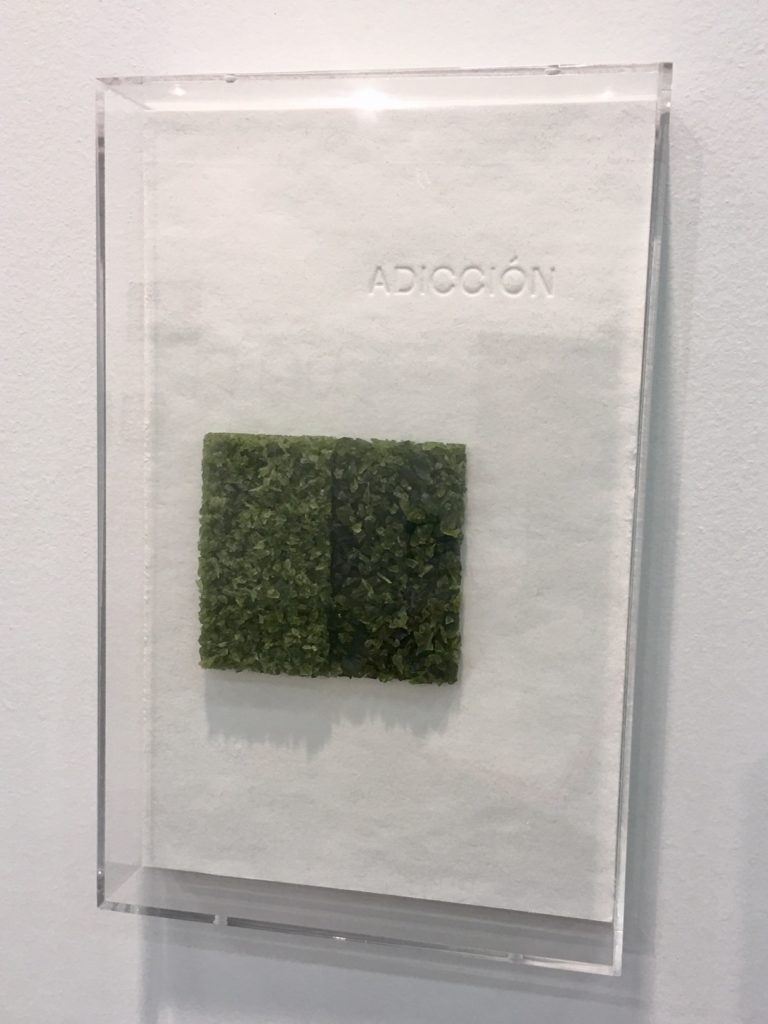

“In the beginning the fair was very closed, with very vernacular works,” said the São Paulo gallerist Eduardo Fernandes, who has been participating for eight years. “The market in this country is still quite closed, but the fair opens it up,” he noted, to collectors from places as far-reaching as Berlin and Singapore. This year, he brought a selection of mixed-media works by Brazilian artist Edgar Racy, priced at $1,500 each, that address longstanding regional concerns of hunger, addiction, and deforestation.

Edgar Racy work made from broken beer bottles at Galeria Eduardo Fernandes, ARTBO, Bogotá, Colombia.

For some Colombian dealers living outside of the capital city, ARTBO offers an extremely rare lifeline to the global market. Juan Sebastián Ramírez runs the gallery (bis) oficina de proyectos in Cali, a city he describes as being “like Berlin 10 years ago: cheap and cool and absolutely no money.” He sells art almost exclusively to clients abroad, in Bogotá, or in the second-largest Colombian city, Medellín. It’s a challenge, he said, particularly because of the continuously poor exchange rates with US currency. “The dollars have gotten more expensive and the debt has grown in the past four years,” he said.

Ramírez was showing paintings and sculptures by the Colombian artist Alberto Lezaca, who was on hand at the booth. The artist said he felt that the creative conditions in the region had improved vastly in the past 10 years. Many of the artists in the generation before him, in their 60s and 70s, stopped making work altogether, he said, “because they didn’t have money.” Now, however, he’s seeing a conscious correction to that reality. “There’s a small movement of collectors buying Colombian art,” he said. “It’s not very strong, but it feels like this generation is supporting us.”

Alberto Lezaca paintings at the booth of (Bis) Oficina de Proyectos, ARTBO, Bogotá, Colombia.

Lezaca’s work consists of reversing artistic mediums: he paints sculptures and builds installations that depict paintings (priced between $1,500 and $11,000 at the fair). “It’s about how we build reality,” he said, “paintings of sculpture, and paintings that propose fake installation art must lie every time.”

Art as a fiction was a recurring theme throughout the fair. The Colombian artist Nicolás Bonilla created a fake geological service for the booth of Salón Comunal, where hundreds of his ceramic “rocks” appear on shelves organized by imagined taxonomies. “I wanted to make ‘real’ what is not real,” Bonilla said, to look at the “relationship between science and art, and how museums have the power of making truths.”

Ceramic sculptures by Nicolás Bonilla at Salón Comunal, ARTBO, Bogotá, Colombia.

Lezaca’s work in particular points to another trend visible at the fair: the hard geometric lines of concrete art, which has a long tradition in South America. “I feel a relationship with my past from Colombia,” he said—some of whom are artists that mainstream art history left behind.

Other dealers, meanwhile, brought work that intentionally pushes against that artistic lineage. “People here are accustomed to cleanness, the line,” said Jorge Sanguino of the Dusseldorf-based gallery Wildpalms and a Colombian native who relocated to Germany as a child. To stand out, Sanguino’s gallery brought the soft, curving abstract forms of American painter Jason Duval, on sale for between $4,200 to $7,200. “This is a very European and American tradition, the repetition of motifs.”

One stark difference at this year’s fair compared to those of years’ past is the visible fallout from Venezuela’s economic crisis, which has caused severe food and medicine shortages and the exodus of millions of people, many of whom are crossing the border into Colombia. For the first time in generations, Colombia is the recipient of immigrants rather than their producer.

“It’s very difficult to sell there and the government has a way to shush artists,” said Caracas-based dealer Luis Romero, who notes his gallery, Abra, almost exclusively makes sales when it travels to fairs like ARTBO. It’s important to him, however, to keep his doors open in Venezuela and to continue supporting the local artists who do remain in the country. “I try to participate in art fairs to get money to do exhibitions” back home, he said.

The fair also allows him to show work that would be censored in Venezuela, such as art that takes a critical view of the Maduro government, or that looks at financial and environmental crises.

In some ways, Venezuela’s loss has been a boon to Bogotá, which is becoming the adopted home to many of Caracas’s wealthiest collectors and most successful dealers and artists.

“Bogotá’s art scene has become the center of the region,” said the artist Nicolás Bonilla. But he is wary of giving in to these stirrings of hope. “What I think is, until when?”