Market

In the Post-Warren Kanders Era, Artists and Dealers Wonder: Should Collectors Be Vetted?

Some artists refuse to sell their work to certain collectors—but plenty of others don’t care to discuss it.

Some artists refuse to sell their work to certain collectors—but plenty of others don’t care to discuss it.

Brian Boucher

The bruising battle this spring that led to the resignation of Warren Kanders from the board of the Whitney Museum of American Art has the art world wondering: What’s next?

This week, answers began to emerge as protesters hit the Museum of Modern Art to demonstrate against board member and art collector Steven Tananbaum, whom activists say has profited from the debt crisis in Puerto Rico. The demonstration came on the heels of another protest, against MoMA board member Laurence D. Fink, the CEO of the investment firm BlackRock, which has large investments in private prisons.

Now, some are wondering how this heightened level of scrutiny could affect the art market. As Miami collector Martin Margulies put it to artnet News: “Do artists inspect the background of every collector who buys their artwork?”

Michael Rakowitz in front of “The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist” in Trafalgar Square. Photo by Caroline Teo.

New York dealer Anton Kern, who represents Nicole Eisenman, one of nine artists who threatened to withdraw from the Whitney Biennial in protest against Kanders before his resignation, told artnet News that he closely hews to the wishes of the artist, a 2015 MacArthur “genius” grantee.

“Nicole has always cared about where her work is placed, and the gallery has always vetted collectors of her work, and all of our artists’ work,” he wrote in an email.

Another Whitney Biennial participant, Nicholas Galanin, an Alaskan artist of Tlingit/Aleut background, is even more direct.

“Using capital to create a project can be as valuable as denying it,” he said in an email. “In 1997, my uncle carved the first totem to be raised in our community in the last 100 years. Holland America, a tourism cruise agency, wanted to sponsor and oversee the event. In order for this event not to be consumed by tourism sponsorship, we denied the funding. The pole still stands.”

Michael Rakowitz, the first artist to withdraw from the Whitney exhibition, was already vetting his buyers before the Kanders scandal explored. His dealers—Rhona Hoffman, Jane Lombard, and Barbara Wien—frequently facilitate conversations between artist and potential collectors.

“I’m very interested in where some of the artifacts in the art and antiquities market are coming from, so I’m also interested in where they go,” Rakowitz said by phone.

Whitney Biennial artists are not the only ones who try to control where their work goes. MacArthur “genius” grantee Cameron Rowland negotiates contracts with potential collectors; some are restricted to renting his work. And William Powhida, whose works often plot connections between institutions and their supporters, included a sentence in the announcement of his recent show, “Complicities,” specifying that some collectors were forbidden from buying his work.

Powhida, the notice says, “will not be selling any of this work to any of the subjects depicted (sorry, Glenn Fuhrman!).”

Philosophical and political divergences between artists and patrons are hardly new.

“This is a very old issue, dating back at least to the Renaissance,” says New York attorney Thomas C. Danziger, of Danziger, Danziger & Muro. “Do you think Leonardo enjoyed working with the Borgias, with whom he was politically mismatched?”

Collectors, of course, profit when artworks grow in value, raising the emotional stakes when artists and dealers are considering to whom they are willing to sell. Kanders, for example, was featured in two separate Architectural Digest stories revealing that among the works in his collection are examples by numerous blue-chip artists, from Gerhard Richter to Richard Prince. (Emails requesting comment sent to more than a dozen of those artists’ galleries went unanswered.)

Still, few dealers can afford to pick and choose. “It’s easy to be on your high horse when your profit margins are good,” said one New York art dealer, who requested anonymity. “But people hop off the horse and walk next to it when money gets tight.”

The ad hoc nature of the art industry, in which galleries write their own rules, militates against shared best practices, but there are codes. Dealers protect artists’ markets by trying to ensure that buyers don’t flip works, and that they are willing to lend to museum exhibitions, for example.

But “know-your-buyer” customs don’t extend to whether collectors have investments in unsavory companies. “That’s an insane amount of diligence,” said a gallery director, who spoke anonymously. “I’m not going to check the investment portfolio of every person who wants to buy a drawing.”

Yet just as there have been calls for greater regulation of the art market, some say there should be ground rules.

“I do think there should be ethical guidelines when it comes to museum board members, or the public and private collections in which the work ends up,” Rakowitz says. “This is not about purity, despite people wanting to frame it in that way.” All the same, he admits: “I don’t have a list of biographical data on everyone who buys my work.”

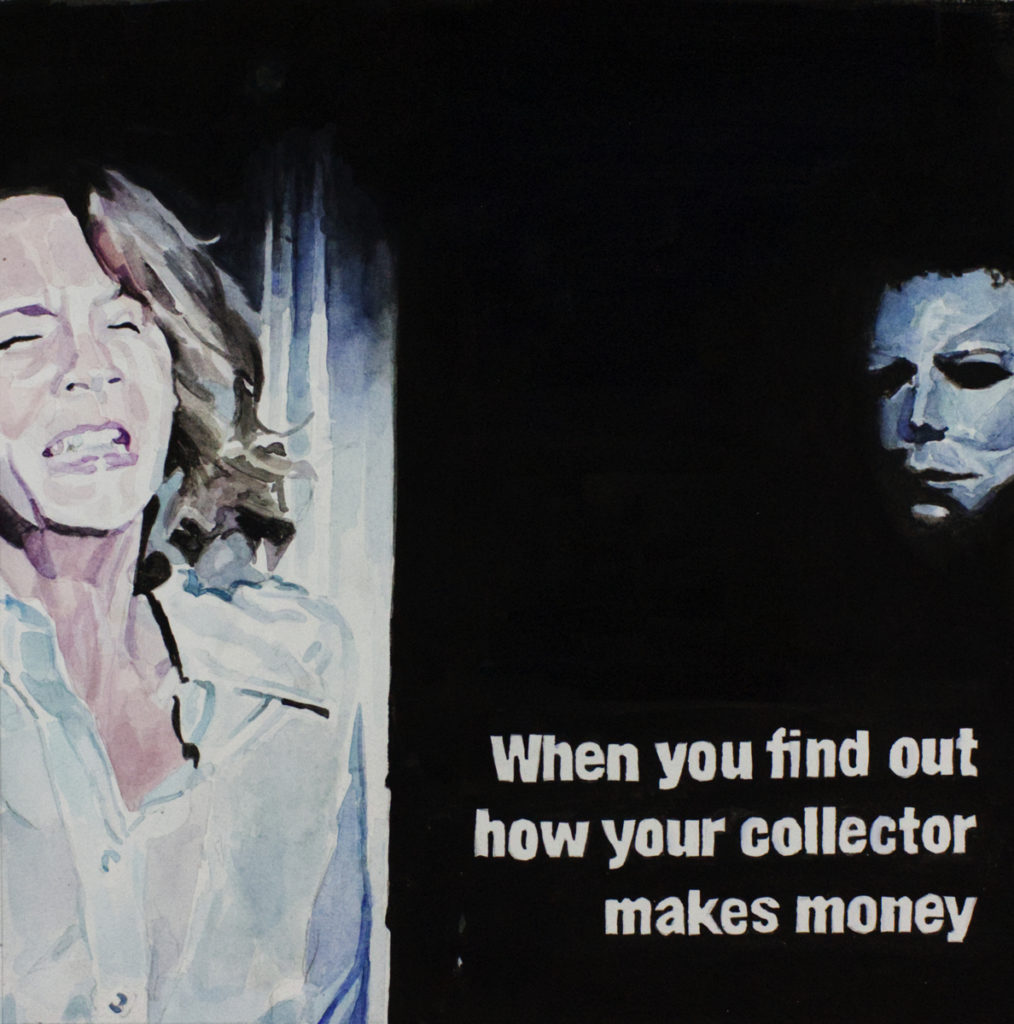

William Powhida, Collectors (Halloween) (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters.

By many accounts, wider conversations about blacklists aren’t happening. Speaking anonymously, two former gallery directors said that in their many years, hardly any artists inquired about who bought their work.

As for those doing the buying, a question remains about whether increased scrutiny on collectors won’t drive them away from art overall. Margulies remains convinced that such concerns are overblown. “Collectors are collectors,” he says. “If they’re real collectors they look at the art, and that’s it.” He did add, however, that he wouldn’t buy a work by an artist who was “the antithesis of everything this country is.”

Ultimately, greater vetting would hinge on frank conversations that may not benefit dealers and artists when their livelihoods could be affected.

“Dealers go to the mat for their artists and are their advocates and advisers,” Maureen Bray, executive director of the Art Dealers Association of America, tells arnet News. “Any decision that can affect the artist’s career and legacy is a serious one that artists and their dealers often make together.”

Bray also points out that the relationships among artists, dealers, and collectors can already be complex. “Some of these relationships are decades long and are more akin to those with friends or family,” she says. “There is an emotional commitment between them that goes far beyond transactions, and centers around support for the artist and their work.”

Still, some ask, what if artists banded together?

“Museums and the market are structurally different: museums claims to uphold public ideals, and can be pressured on those terms,” said one museum activist, speaking anonymously so as not to involve the organizations they work with. “But, acting collectively, could artists use their power to channel the resources of the art market as well?”