Art & Exhibitions

artnet Asks: Chalk and Marker Pens Artist Dong Dawei

The most mundane tools can yield the most extraordinary results.

The most mundane tools can yield the most extraordinary results.

Zoe Li

Dong Dawei knows his tools like the back of his hand. He knows exactly how many seconds he must hold a marker pen to paper in order to form an ink mark the size of a thumbnail. He meticulously records dozens of ways that ink marks can fan out and merge with other marks, when they are dry, semi-dry or still wet, depending on the climate and the manufacturer.

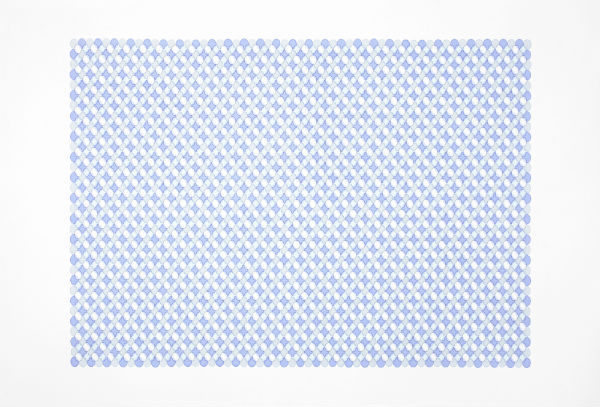

With these in mind, the Beijing-based artist painstakingly creates vibrant patterns of ink. The resulting images have literal references—cobalt blue motifs make a rectangle directly evoking the Ancient Egyptian’s Pool S1 (2013) of its title—but the works pulse with an energy that can only come from absorbing the incredibly focused attention of a solitary artist who repeats a minute action ad-infinitum.

When we met with Dong in Hong Kong’s Galerie Perrotin, he had finished setting up his marker pen works for his first solo show in the territory and was putting the last touches to a site-specific chalk drawing. The six-meter wide wall is covered in thick layers of chalk marks the colors of a sunset. But it is the chalk powder that has fallen on the floor in front of the wall that unexpectedly outshines the drawing itself.

Dong celebrates the beauty in so-called by-products of creation—ink marks, chalk powder leftovers—in an ode to his tools. artnet News caught up with the artist on the eve of his show’s opening.

Dong Dawei creating his chalk installation at Galerie Perrotin Hong Kong.

Photo by Zoe Li

How do your chalk pieces depart from your ink series?

The chalk pieces are more direct and subjective. They are about the material, the chalk, but also function as works that exceed their own boundaries. Drawing is a two dimensional thing, but in the chalk works it becomes almost three dimensional as the fallen powder comes out of the conventional frame.

It also seems to play with a fourth dimension, time, as it is characterized by impermanence, chance, and instability.

These pieces really are time-based and procedural. They also have a sense of immediacy. The chalk work in the show has an intimate relationship with the immediate environment. Wielding the tension between space, work, and its own sense of impermanence is what gives it significance. Drawing normally gives a tidy result that exists within its conventional frame, here there is an element of time passing in the end result of the work that alludes to its creation process.

What is more important: the journey or the destination, the creation process or the end result?

If you only gave me two choices and forced me to pick one, then I’d say the end result is more important, but this is always determined by its process. Getting between one point and the next involves many things. Just like the protagonist of the Dream of the Red Chamber [Editor’s note: this 18th-century novel by Chinese author Cao Xueqin is of China’s Four Great Classical Novels, according to Wikipedia]: he was a heavenly being who came to down to Earth to experience the suffering and futility of human life, but that was the colorful part of the story.

Dong Dawei Egyptian Swimming Pool (2014) marker pen on paper, 80 x 120cm.

Image courtesy of Galerie Perrotin.

What attracted you to the tools you use?

I didn’t invent these methods or techniques of drawing, I merely rediscovered them. These are everyday materials that can be found easily, but it is up to you to reveal their full potential.

On the market we can see many different tools (markers and chalk), each of them have different characteristics. You have to bring many different kinds home and try each of them to see their individual characteristics and then design your work according to your material. This turns the creative process on its head — we are creating a work because of the characteristics of the tools, we are making works because of the tools.

I can imagine that the reality of the creative process is arduous and lonely. Is the hermetic nature of drawing important to you?

Hermetic nature of the work is a by-product and not a goal. When you create these works you are forced to learn patience and to physically train your body for it. But this is not something that needs to be deliberately communicated to the public, it is for the artist himself. Yet when the audience sees the form of the work they will automatically sense what the artist has been through.

Dong Dawei “A Singular Point” is on view at Galerie Perrotin from January 16 to March 4.