Art & Exhibitions

artnet Asks: James Nares

The non-objective painter and filmmaker explains how the art world works.

The non-objective painter and filmmaker explains how the art world works.

Lorraine Rubio

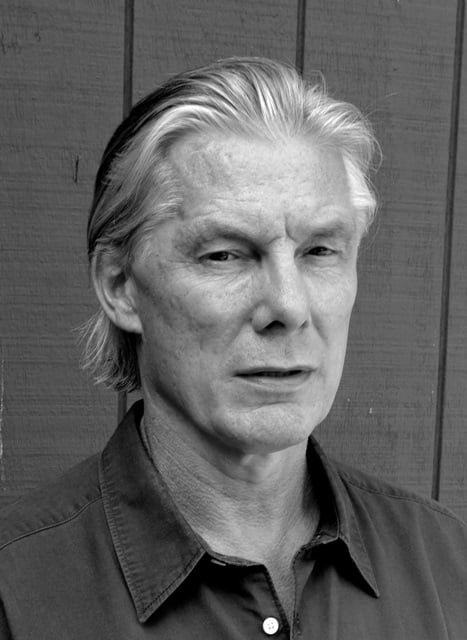

Working with brushes of his own design, British painter James Nares is most known for his paintings attempting to capture the moment of their own creation. These finished paintings usually consist of a single brushstroke, though the process of making is varied, with many drafts until he finds a satisfying balance between spontaneity and purpose. Born in London, UK, Nares attended the Chelsea Art School in London from 1972 to 1973, before studying at the School of Visual Arts in New York from 1974 to 1976. In his early years in New York, Nares was a punk- influenced No Wave musician, filmmaker, and performer. His films and paintings are held in many collections, including at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Anthology Film Archives, and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. artnet News caught up with the painter days before his upcoming show of “high-speed drawings,” opening on September 10 at Paul Kasmin Gallery to talk about the booming art scene in New York, and his start as an artist in New York in the mid-1970s.

When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

Well, I kind of always wanted to be an artist. Or at least I never wanted to be anything else. The only other thing I was aware of wanting to be was a soldier standing guard above the Suez Canal, but I don’t know how long that lasted, probably about a week. I do remember [wanting to be an artist] though, a whole lot, and I always did things that were heading in that direction. I remember painting the neighbor’s roadbed entrance with bright red enamel paint, like household enamel. And I remember being given a whole bunch of old 78 RPM records and throwing them up in the air so they came down in the lawn like a knife blade or something, and the whole [yard] was filled with embedded 78s, it was beautiful. I was always doing different things, and I got great support from my family, which was lucky. Now that I’m older, I hear about friends of mine who didn’t have that kind of support. My parents were always happy that I knew what I wanted to do, and helped me in any way they could.

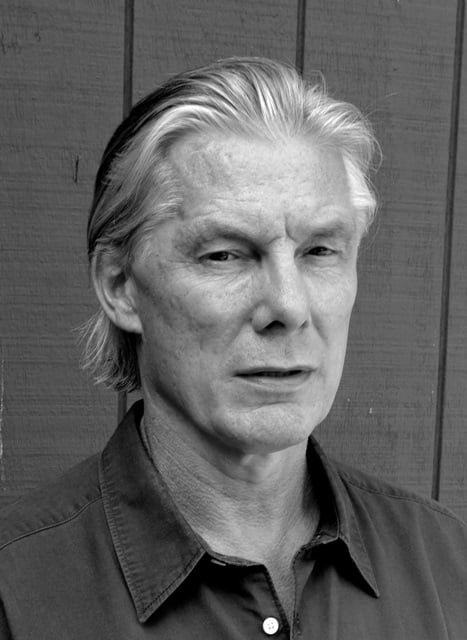

James Nares, Others Call it Day (2011)

Oil on linen, 75 x 63 in.

Photo courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

What inspires you?

So many things, so many people. I have a natural interest in things that move and things that sore and things that fly. I guess there’s a kind of internal equivalent to all of those things, an emotional scale or something. Movement is the thing that catches the eye. That’s why having a video monitor in a gallery full of drawings to me is a no contest, because the eye always goes to the thing that’s moving. There’s a reason for that, maybe because we’re hunters.

I have been thinking about people that inspire me the most, because my daughter right now is embarking on a career doing much the same thing I did. The people I got the most from, at least in the beginning, were my friends and peers and the circle I came of age with. I think the kind of ideas we gave each other were really stimulating. I never had any great teachers. With friends I can remember things that kept me up all night thinking, like something that somebody said.

Every single art magazine and art book that I ever looked at before I was able to actually go see the art; I got a lot of my inspiration from magazines like Avalanche with Lize Béar in the early 1970s, and really all of those magazines in the early 1970s, like Studio International in England. I was slipping away from Artforum at that point into something slightly different, more toward Walter Robinson’s Magazine ART/WRITE —I knew him by Mike Robinson, I still call him Uncle Mikey sometimes. I think Artforum got a lot from ART/WRITE. It was a new kind of tenor in the field of art writing, it had reverberations. A lot of the writing was done by artists, and I think Walter did a lot of the writing. They did an issue with Robert Ryman I remember I loved. They never quite followed one party line, they had a voice all their own.

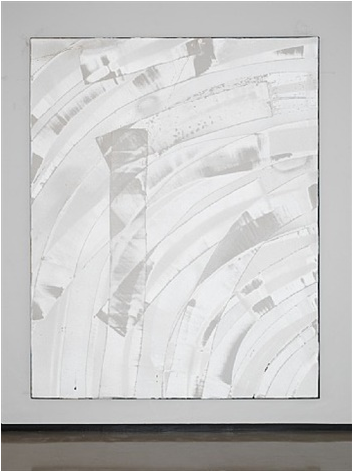

James Nares, Hit the Road (2013)

Thermoplastic on linen, 120 x 96 in.

Photo courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

If you could own any work of modern or contemporary art, what would it be?

That’s funny, it’s like stepping over to the other side. I usually think of some enormous or monumental piece, but there are so many. I wouldn’t mind a Richard Serra curved steel presence in my own home or in my garden or in my life. I’m very partial to him. There are a number of pieces by friends of mine. There are one or two of Christopher Wool’s paintings that I would love to have. It’s all black and white.

There are so many great artists, I’m just astonished. When I came to New York, it seemed like the art world, you kind of knew everybody in a way. Everybody knew everybody, it was small. But now there are so many artists it’s kind of breathtaking, there might be a lot of crap being made, too. But still, it’s good that there are so many people doing it. I like the young energy. My daughter Sasha had a popup show last night.

How was it?

It was great! The work and the atmosphere were good. They did it in the L Lounge on First Avenue and Houston. It was a one-night event. They hung the show for the opening party, and they put little cue codes next to everybody’s name, so you could take your phone and swipe the cue code and learn about each artist. It was really clever. The work was good, and the kids were all excited. It reminds me of myself a long time ago.

James Nares, That Mississippi River Painting (2001)

Oil on linen, 81 x 68 in.

Photo courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m currently working on my “high speed drawings,” which I’m going to show at Paul Kasmin Gallery, opening on September 10. They are large drawings made on large sheets of paper that I wrap around a large steel drum, which is connected to a motor that spins very fast. I go into it with a brush that I made with a connected ink bottle to the top, so I don’t have to dip it in ink. Its fed from the inside the whole time, and I do these drawings—I call them drawings because it’s all line, they’re like ink drawings—they make these linear objects on paper, I don’t know what to call them. I’m really looking forward to seeing them all installed in the gallery all together because I’m hoping it will be a head-spinner, literally.

I’m always working on movies, too, small ones. But I probably shouldn’t talk about those because I always end up doing something different than what I say. I can’t go back on the high speed drawings, but I might change my mind about a film I put out in the world. I’ll wait till I’ve made it.

James Nares, Speed of Heat (2012)

Oil on linen, 81 x 63 inches

Photo courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

When not making art, what do you like to do?

I like to put my feet up. I don’t watch TV. I like to play three cushion billiards, where you don’t have any pockets, and it’s like a game of geometry, really.

So what’s winning the game?

There are only three balls, two white and one red. One of each of the white balls belongs to each player, and you have to hit with your ball one of the other two balls and three cushions in any combination. I’ll sum it up like this: you have to hit at least one ball and three cushions before you hit the second ball. So you could hit cushion, cushion, ball, cushion, ball; or you could hit cushion, ball, cushion, cushion, ball; or you could hit ball, cushion, cushion, cushion, ball; and the list goes on—I’m beginning to sound like a record player. It’s sometimes called carom billiards, I like it. Otherwise, I’m slightly one of those people who’s always working, and if I’m not, I’m usually just taking it easy. I have a lot of things I want to do.