Art & Exhibitions

artnet Asks: Jim Shaw, Creator of Apocalyptic Visions

Welcome to the wonderful world of Jim Shaw.

Photo: Lee Ann-Nicke

Welcome to the wonderful world of Jim Shaw.

Amah-Rose Abrams

The complex, layered works of Jim Shaw combine found theatrical backdrops and photorealistic painting. In their subject matter they address the complicities of American society, tackling food production, religion, myths of Hollywood, his invented religion “Oism,” and issues of the self. His depictions are mixed with visual references to advertising and Hollywood, while sometimes adopting B-Movie aesthetics. In 2000, Shaw staged a large exhibition at the ICA in London that consisted of paintings he had bought in thrift stores—a show that caused uproar among critics.

As a student at Ann Arbor University, Shaw met fellow artist Mike Kelley with whom he formed the band Destroy All Monsters in 1973. Both went on to become successful artists, though Kelley was certainly the better-known of the two. But 2015 has been a great year for Shaw. He has two museum shows currently running in the United States, “Jim Shaw: Entertaining Doubts” at MASS MoCA, “Jim Shaw: The End is Here” at the New Museum, and a concurrent solo exhibition simply titled “Jim Shaw” at Simon Lee Gallery, in London.

On view at Simon Lee are works addressing topics such as slavery, explored by tale of Rumpelstiltskin and a diptych involving George and the Dragon and John Wayne. We sat down with Shaw to find out more about his work and the way his mind works. But first he tells artnet News he thinks the iPhone is the antichrist. And so, we get down business.

Jim Shaw The Third Angel (2015)

Photo: courtesy Simon Lee

Can you tell us a bit about the series of works on view here at Simon Lee? There seem to be ecological issues raised in some of them.

I honestly think that along with the introduction of the iPhone and of genetically modified foods, you can’t predict what’s going to happen over time, genetically modified corn being the biggest element of that. I try not to be too heavy handed with these metaphors; that’s why a lot of the time I flip things back to the gilded age instead of working with the present.

Jim Shaw St. George and the Dragon (2015)

Photo: courtesy Simon Lee

I was really captured by St. George and The Dragon (2015), could you discuss the imagery in this painting?

It’s another version of man’s subjugation of nature. It’s based on a couple of myths. One is the myth of St. George and the Dragon and that’s obviously the Christian subjugating the pagan. The dragon becomes [the fantasy fiction series] The Worm of Ouroboros, so I crossed that with this other myth, making this kind of diptych.

There was a movie made in the mid 1950s called The Conqueror (1956) starring John Wayne as Genghis Khan and Susan Hayward as an Asian bride who he steals for himself. It was directed by Dick Powell, produced by Howard Hughes, and shot around St. George, Utah, which is a Mormon area and was very close to an atomic testing site.

A lot of people in the area were getting cancers, and John Wayne and Dick Powell both also died of cancer. There’s a belief that there’s a direct causal relationship, plus it was an absurd film.

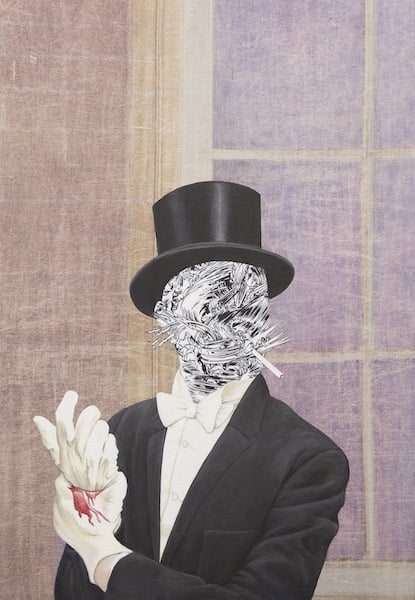

Jim Shaw Man With Top Hat(2015)

Photo: courtesy Simon Lee

Would you say that there’s an overarching theme to all the works in the exhibition?

It’s just stuff I think about, all this apocalyptic stuff. The truth is that we’ll probably all be here tomorrow, but ever since the era, in the 1970s, when the disaster film was prominent, I’ve been interested in that, and drawn to all that kind of stuff.

Around the time that the film Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) came out, that was when I did my first “religion,” and the title of the show and magazine it inspired was “The End is Here.” I thought people really were bored with late capitalism. It was at the point where you are no longer in survival mode really but life is still a daily struggle and it’s kind of boring.

I think that I have a schizoid nature—if you start off as schizoid then you could become schizophrenic or manic-depressive. I am manic, but not severely, and I am alienated, but not severely. I have some emotions that are damped down.

Do you think that’s why you express yourself through art to the extent that you do, writing down your dreams for instance?

I was watching Love and Mercy (2014), about Brian Wilson and how he was overcome by insanity, by sound, by these echoing sounds. I have a visual version of that. It’s not as overcoming and I am not as crazy as he was; I’m also not as good a composer as he was. As someone who is alien from the world, his music is very emotional.

Jim Shaw, Prometheus Liver is the Cock’s Comb (2015)

Photo: courtesy Simon Lee

You have had an amazing year so far, with shows at MoCA and the New Museum. Do you enjoy putting on these large-scale exhibitions?

It’s the manic thing that takes over. When someone tells you, “Well we’ve got this giant space, and here’s a little bit of production money,” your manic side can probably take over. It’s sort of enjoyable.

The best part of the manic phase is having ideas; my working is bifurcated into the having of ideas and making of objects. The making of the objects is almost like a depression, not a depressed depression but you’re in this state when you are to render something and it takes X amount of time.

There was such a strong reaction to your exhibition “Thrift Store Paintings” at the ICA in 2000. Do you feel as though the art world is now more open to an alternative aesthetic?

It’s more open to it but still, [that work] is not commercial, it’s not good taste, and it’s not predictable. You can’t look at work that’s got all this stuff happening in it and just have it sit quietly in the background. Yet what the mass of collectors want is something that is recognizably worth money and sits quietly in the background.

Jim Shaw King Cotton (2015)

Photo: courtesy Simon Lee

Do you feel like taking a surreal approach and using very accessible imagery makes it easier to tackle the big issues like religion, politics, and slavery?

It’s not like anybody in the art world doesn’t already believe that stuff anyway. You’re kind of preaching to the converted, so to do it directly is kind of a little dopey.

I’ve been researching and doing more work around the impact of slavery but actually I think that the impact of everything that has happened since then has been worse.

How did your invented religion, Oism, evolve from the initial project into the narrative that runs through your work today?

Well it should have come and gone very quickly but because it was based on research and inspiration… I was doing these multiple bodies of work while I was developing Oism, and I’m still trying to develop Oism. I’ve been wanting to develop the Oist rock opera but I always have these deadlines.

Right now I’m between deadlines so I’m trying to start recording and hopefully I’ve got a lot of concepts, for a few melodies, and maybe a couple of lyrics.

Are you looking forward to getting back into music?

Yeah. And also, the older I get the harder it is for me to sing in tune. I can’t really delay it any longer. I listen to myself sing and I’m reminded of Mark McCarthy whose voice kind of warbles now and I’m much younger than he is.

“Jim Shaw” in on view at Simon Lee Gallery, London from November 18, 2015 – January 9, 2016.