Galleries

artnet Asks: Laylah Ali

Ali's current solo show at Paul Kasmin has been in development since 2011.

Ali's current solo show at Paul Kasmin has been in development since 2011.

Cait Munro

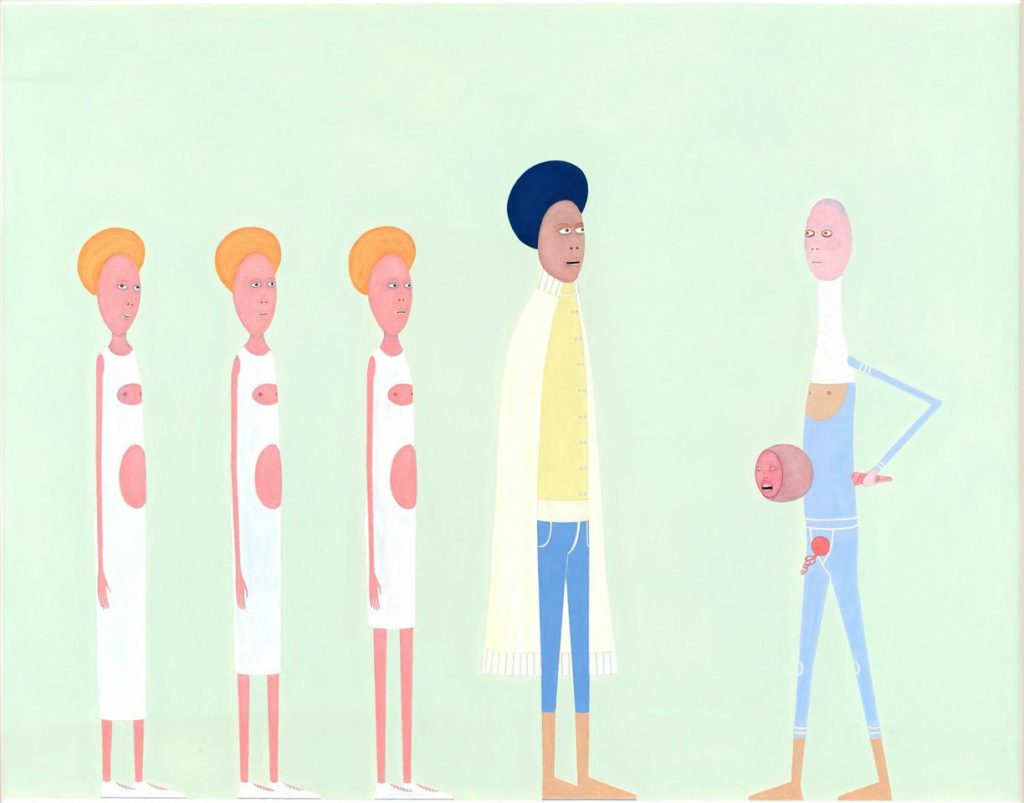

Laylah Ali, Untitled (Acephalous series) (2015).

Photo: Courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery.

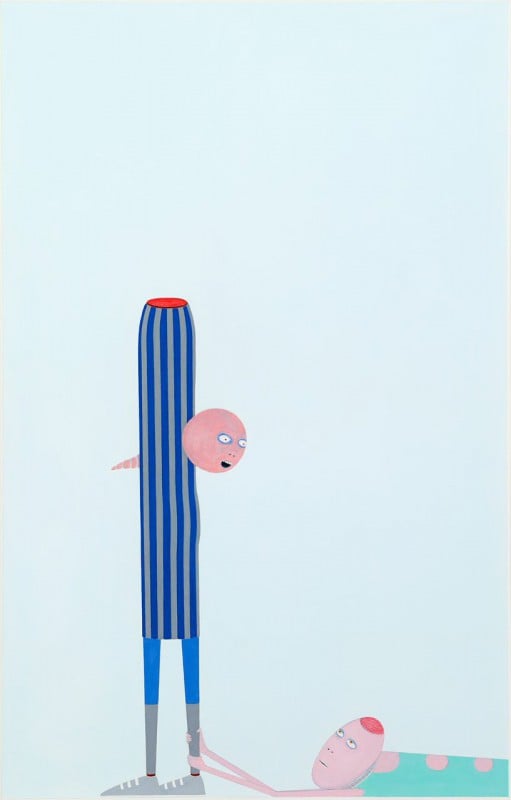

Laylah Ali is a Massachusetts-based painter and a professor at Williams College. Ali is best known for gouache paintings that depict a fictional race known as the Greenheads—ageless, genderless, racially ambiguous characters who act out a variety of social situations, often in a cartoon-strip format. These detailed figurative paintings often take months to complete. Ali’s work has been exhibited at the 2003 Venice Biennale, and the 2004 Whitney Biennial. Her current solo show at Paul Kasmin Gallery has been in development since 2011.

How did the idea for the Greenheads figures, for which you are widely known, come about?

I started the Greenheads in 1996. I had been drawing loose heads that were not attached to any bodies. I did that for a couple of years after art graduate school—green, pink, and brown heads with their tongues often sticking out like they were sick or vomiting. But the fusion of a pseudo-superhero body with a masked green head happened that summer at an art residency where I was alone with new tubes of gouache and little human interaction. I wanted to make a figure that acted like a question mark. I actually have revisited some of those pink heads in this newest show.

Your new series at Paul Kasmin debuts a new series of characters. What can you tell us about them? How are they different from the Greenheads?

It is no longer a mono-racial group, as the Greenheads mostly were. These figures are also more gendered. There is modest genitalia of some sort, and they are larger when compared to my previous work.

In your paintings, the figures are often engaged in very charged social situations. How do you conceptualize what these situations should be and then translate them into visual images?

I do months of pencil sketches and then pare them down to as barebones as I can make them while still keeping them reactive. It is important that each painting carries not just one story, but several, and that it has multiple access points. That is true of the individual characters as well. I am influenced by what is happening around me—in the USA, these are the Obama years, and I am paying attention to that. The ubiquitous narratives of “terrorism” and the attending storylines are also of interest, though there are some deeply personal threads that wind their way through the paintings. Those are a few examples.

Laylah Ali, Untitled (Acephalous series) (2015).

Photo: Courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Your work deals with complex issues like race relations in a relatively lighthearted way, visually speaking. How do you strike that balance?

I don’t think of them as cheerful or carefree, but they do have an open and not-unfriendly presentation. The initial access to the paintings is one that does not necessarily announce my full intentions if you end up spending more time with them. So I think in some ways I use formal methods, including color, to allow more complicated or unpleasant things to occur if you want to stay with them and go to those other places.

What does a typical day in your studio look like?

A cup of tea in an unwashed cup to transition to my studio once I arrive and then finding the right thing to listen to while working on hours of detail work. Losing and finding my metric ruler. Cutting white erasers with an X-Acto knife over and over to get the sharpest edges. Late night BBC news reports and wondering why they have to be so repetitive for such a well funded operation. And then: almonds, crackers, and water to keep me functioning. Chocolate. Bouts of depression that are pushed aside by the need to keep working.

What inspires you?

Music, walking briskly in the freezing cold, reading about US history. Sometimes, other people.

Laylah Ali, Untitled (Acephalous series) (2015).

Photo: Courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery.

When did you know that you wanted to be an artist?

Late, like when I was 30, though I was doing all the things you might do to become an artist in my 20’s.

Who are your favorite artists?

That changes for me over time, of course, but I like to see what Deborah Grant is up to, and I am a Charles Burchfield fan.

If you could buy any piece of modern or contemporary art, what would you buy and why?

The last work of art I truly coveted was one of Charles Gaine’s graphite music score drawings from his Paula Cooper show in 2013, where he translated important historical manifesto-type texts into hand drawn musical scores. It was moving and meticulous and somewhat mysterious in how he made the words into musical notation. I was really taken by them.

Laylah Ali, “The Acephalous Series” is on display at Paul Kasmin Gallery from March 25—April 25.