Market

The Bankerization of the Art Market: How Wall Street’s Masters of the Universe Infiltrated the Art World

What happens when a market that used to be helmed by patrician connoisseurs is overrun with bankers from Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan?

What happens when a market that used to be helmed by patrician connoisseurs is overrun with bankers from Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan?

Nate Freeman

A version of this story first appeared in the spring 2020 Artnet Intelligence Report.

Art dealers were on vacation when Patrick Drahi pulled off the biggest deal many of them had ever seen.

It was June 2019, right after Art Basel, a fallow period when gallery honchos and auction chairmen rent homes in Italy or go island hopping in Greece. Drahi, a telecom billionaire in charge of the multinational corporation Altice, plunked down $3.7 billion in cash and debt to acquire Sotheby’s, which had been traded publicly for more than three decades. Less than two years after the art world had watched, aghast, as a buyer believed to be Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman spent $450.3 million on Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, a man had stepped up and paid more than eight times that—not on an artwork but on a chunk of the art world itself.

Patrick Drahi, Sotheby’s new owner, in 2016. (Photo by Christophe Morin/IP3/Getty Images)

This, presumably, was good news for Tad Smith, the CEO of Sotheby’s for the past four years, who had led a slew of acquisitions that transformed the company into a microcosm of the entire art market, a one-stop shop for collectors who wanted all their needs taken care of under one roof. Better yet, Smith and Drahi had a history: when Drahi was in talks to buy Cablevision from James Dolan, Smith was CEO of Madison Square Garden, which Dolan has owned since the 1990s.

“This acquisition will provide Sotheby’s with the opportunity to accelerate the successful program of growth initiatives of the past several years in a more flexible private environment,” Smith said in a statement after Drahi’s purchase.

Former Sotheby’s CEO Tad Smith overseeing a sale in Hong Kong. (Photo by Jayne Russell/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

But less than six months after the deal was announced, Smith and Drahi parted ways, and the CEO walked away with a golden parachute check for a whopping $28 million. To replace him, Drahi hired Altice CFO Charles Stewart.

Drahi wanted one of the world’s largest art businesses to be run by a banker.

When it comes to financial types infiltrating the art world, it appears the barbarians are at the gate. Bankers were once content to be on the relative fringe of the picture-buying business, using their bonuses to bundle Warhols or clawing their way onto museum boards through conspicuous gift giving. Now, they’re running auction houses, opening galleries, building private museums, and whispering in the ears of billionaires as art advisors.

Sure, the machers of the banking industry have deep roots in the art market—the Medicis fueled the Renaissance, the bankers of the East India Company let Rembrandt put up his paintings as loan collateral, and the robber barons used their money to build the Frick and the Morgan. But today, bankers don’t just want to be patrons—they want to be players, occupying roles once filled by art experts. It’s Wall Street meets Chelsea—a mash-up of the Tom Wolfe classics The Bonfire of the Vanities and The Painted Word.

Part of the reason for this sea change is simply that financial types see the market for art as one they can streamline. “When I was at Sotheby’s, the business was run entirely by art brains, not by business brains,” said art advisor Wendy Cromwell, who worked as a vice president in the postwar and contemporary art department at Sotheby’s in the ‘90s. “That led to a lot of dysfunction and a lack of profitability. It was a business that was ripe for professionalizing.”

Robert Mnuchin (left) with Steve Cohen. ©Patrick McMullan. Photo: Sylvain Gaboury.

One of the first bona fide Wall Street-to-art world crossovers was Robert Mnuchin, who retired from Goldman Sachs, where he pioneered the firm’s first block-trading operations, to open a gallery on the Upper East Side in 1990. At first, sources say, Mnuchin was seen as the epitome of a gentleman banker who was fulfilling a lifelong dream of curating gallery shows. But then he became “a more aggressive version of that,” one market player said. Just last spring, Mnuchin placed the winning, $91.1 million bid for Jeff Koons’s Rabbit—on behalf of another financier, hedge-fund manager Steve Cohen.

Thirty years after Mnuchin set up shop, a new guard of bankers is encroaching on the art world. The auction house Bonhams, a perennial fourth-place finisher behind the Big Three, was acquired by a private equity firm, Epiris, in 2018.

Meanwhile, Adam Chinn left his corner office at the boutique investment firm Centerview Partners to join the advisory firm Art Agency, Partners, which was bought by Sotheby’s in 2016, and later served as the auction house’s COO. At times, it was jarring to see the former banker taking bids on the phone among the lifers with art-history degrees. After Chinn was pushed out in 2018, he took an even more inside-baseball position in the art world: art advisor to the all-powerful Mugrabi family.

Wall Street Bull Sculpture.

But the individual who could have the most impact bankerizing the mechanisms of the art industry is Stewart, who spent nearly two decades buying size at Morgan Stanley, where he became the deputy head of investment banking for Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. He arrives at a critical moment for Sotheby’s, which took a haircut on sizable guarantees in recent years and, in 2019, reported $108.6 million in net income from $6.4 billion in sales, a slim 1.7 percent margin.

Perhaps the way forward, in Drahi’s and Stewart’s minds, is to think like bankers.

It was clear as soon as Stewart arrived that he was approaching things differently. Six weeks after he started, in mid-December 2019, he announced a fundamental restructuring of the auction house, creating two divisions: “fine arts” and “luxury, art, and objects.” The former encompasses private sales, Old Masters, 19th century art, European art, prints, and photographs (in other words, the art side of the business). The latter includes jewelry, watches, wine, design, and books.

Stewart described the two divisions in an email to staff as “equally important.” The luxury categories, he wrote, present a “major opportunity to further develop new sales channels, including marketplace, e-commerce, and even retail—putting us on a path for future growth.”

The reshuffle suggests that Sotheby’s may move away from relying on big-ticket art auctions—which often require aggressive and expensive business-getting strategies (not to mention highly specialized talent)—and instead place more emphasis on the lower-priced but still-pricey luxury goods game. Luxury goods companies posted an income margin of around 20 percent in 2018, according to a report from Bain & Company—exponentially higher than Sotheby’s.

“The Apollo Blue” and “The Artemis Pink” diamonds, mounted as earrings, at Sotheby’s. Photo: FABRICE COFFRINI/AFP via Getty Images.

In fact, the market for personal luxury goods reached a record high of €260 billion in 2018, up 6 percent from the year before, Bain reports. Compare that with global fine-art auction sales, which grew 4 percent in 2018 and dipped 11 percent in 2019, to $13.1 billion, according to Artnet data. Plus, with the luxury goods market, you don’t have to bank on a well-timed death or divorce. The material is more accessible to buy and more easily available to sell.

It doesn’t take an expert in financial derivatives to see the writing on the wall. Other auction houses are moving in this direction, too. In recent years, Christie’s, Bonhams, and Phillips have all expanded or are planning to expand their sales of designer handbags, watches, and jewelry.

Still, it remains to be seen whether this is a winning strategy. Can auctioneers really compete with established luxury conglomerates? And will specialists who have decades of experience be willing to compete for resources with handbag and watch experts, let alone take direction from moneymen who can’t tell their Monet from their Manet?

“Charlie Stewart has excellent operational experience, and Sotheby’s as a company needs excellent operational experience,” Cromwell said. “But someone with a banking background is—I don’t know how to put this, but it’s never worked in the past. There’s always pushback from the rainmakers, the specialists that bring in the collections that sell the most and make the money. There’s always a lack of understanding between the two sides. So I really don’t know if they’ll be able to make this work.”

Collection from Sotheby’s collaboration with High Snobiety. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Unless, perhaps, they marginalize the individual rainmakers. Looking ahead, Sotheby’s could become a consumer-facing financial-trading operation, buying and selling assets with its clients in mind, swapping around tranches of value. Something that resembles a bank.

“Sotheby’s can interact with customers in almost every facet of what they touch in fine art or luxury goods—we can sell Picassos to buy Old Masters and sell Old Masters to buy a Rolex and sell a Rolex to buy a mid-century French chair,” said David Schrader, the head of private sales at Sotheby’s, who used to be—you guessed it!—an institutional salesman at J.P. Morgan.

“We can touch so many parts of people’s lives, which is for me super exciting, and super exciting for Charlie as well. And it’s something that’s not that different from the way we looked at our biggest, most invested customers on Wall Street. For these customers, if they’re a hedge fund or company transacting in so many different buckets—we’re thinking, how do we serve them synergistically?”

Charles Stewart studied at Exeter and went on to Yale. While at university, he played squash and pursued a liberal arts degree, intent on teaching or doing service work after graduation. “I really had no idea what i-banking was other than the notion that it involved a massive sellout,” Stewart told the Yale Daily News in 2007, when he swung by New Haven for a Calhoun College Master’s Tea.

(Like many of the ex-bankers cited in this story, Stewart declined to be interviewed. A spokesperson for Sotheby’s said that the CEO has not spoken to the press since starting in his new role and was “right in the middle of working out when he wants to start, and on what topic.”)

Charles F. Stewart, chief executive of Sotheby’s. ©Sotheby’s.

Despite his previous aversion to the profession, Stewart found himself in a job at Morgan Stanley in 1994, two years after graduating. He went on to initiate a Brazilian presence for the company in the late 1990s and eventually became the deputy head of investment banking for Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, before defecting to Itaú BBA, the largest investment bank in Latin America, where he became CEO. He didn’t last three years—he was poached by Drahi to become copresident and CFO of Altice USA at the end of 2015. His compensation package was worth $3.8 million, the second highest at the company.

The timing corresponded with a monster deal that Drahi had put together. He spent $17.7 billion to buy Cablevision, going deep into debt to form the fourth-biggest cable operator in the US. Stewart was promptly given his brief: cut $900 million in costs in 2016 alone. He had to do so without implementing layoffs—there was a rider that prevented any job elimination for five years. But the Wi-Fi service Freewheel was shut down, and perks were thrown out the window: top-level executives had to give up their suites and helicopter rides and eat at the company cafeteria.

“That’s our whole philosophy,” Stewart told the Wall Street Journal about the cost-cutting. “It triggers a discussion at a very nitty-gritty level, which is where the difference is made.”

After serving as an effective foot soldier during the Cablevision transition, he got the call to head up Sotheby’s, his boss’s shiny new plaything. The press release quoted Drahi praising Stewart’s “appetite for innovation” and insisted he would “create value for Sotheby’s clients”—but nowhere did it say he had any experience in the art world.

Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Evening sale in November 2019. Courtesy Sotheby’s.

When Stewart arrived in the New York salesroom for the Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern evening auction on November 13, he was standing in the same spot once occupied by Smith, between two phone banks stuffed with specialists probably worried about losing their jobs. As auctioneer Oliver Barker implored the room to bid on a Picasso that would hammer well below its $12 million estimate, he betrayed no emotion.

In the next few weeks, Stewart began to implement layoffs of 20 to 30 senior employees at the auction house and set in motion a plan that longtime Sotheby’s employees with multiple art degrees found destabilizing. In a memo sent out before Thanksgiving, Stewart referred to what he called “our most undervalued and underutilized asset.” But that asset wasn’t the ability to secure consignments or a knack for pricing abstract paintings. The underutilized asset was “data.”

Schrader, the private-sales head, can relate to Stewart more than many members of Sotheby’s brass. For decades, he had been a canny collector while working on Wall Street, using his bonuses from Bear Stearns, Credit Suisse, and then J.P. Morgan to snap up works from Chelsea galleries. Often, he made what turned out to be brilliant purchases—for example, he secured a Richard Prince “Nurse” painting from Gladstone Gallery in 2003 for $60,000 and five years later put it up for sale at Christie’s, where Larry Gagosian bought it for $4.2 million.

He put the proceeds back into art, and all that trading got him close to art-world figures like Amy Cappellazzo, who at the time of the “Nurse” sale was deputy chairman of Christie’s Americas. Fast-forward eight years, and Cappellazzo is leading the fine art department at Sotheby’s, trying to find someone to pump up private sales.

“It was sort of a vision,” Cappellazzo said. “I was at a client’s house for dinner, and I remember being very ill with a cold, and I had taken some cold medicine, which I don’t do very often, and I got this kind of hallucination that I should hire David Schrader to run private sales.”

He said yes. The appointment was a bit of a surprise, as it marked the first time the house had looked to leverage a Wall Street banker’s client list since 1996, when it brought on Jamie Niven, a corporate raider at Lehman Brothers who went on to spend two decades at Sotheby’s as a chairman of the Americas.

Schrader took on a department that had been struggling in recent years. In the third quarter of 2015, total private sales plunged 45 percent, to $85 million, its lowest level for a quarter since 2011.

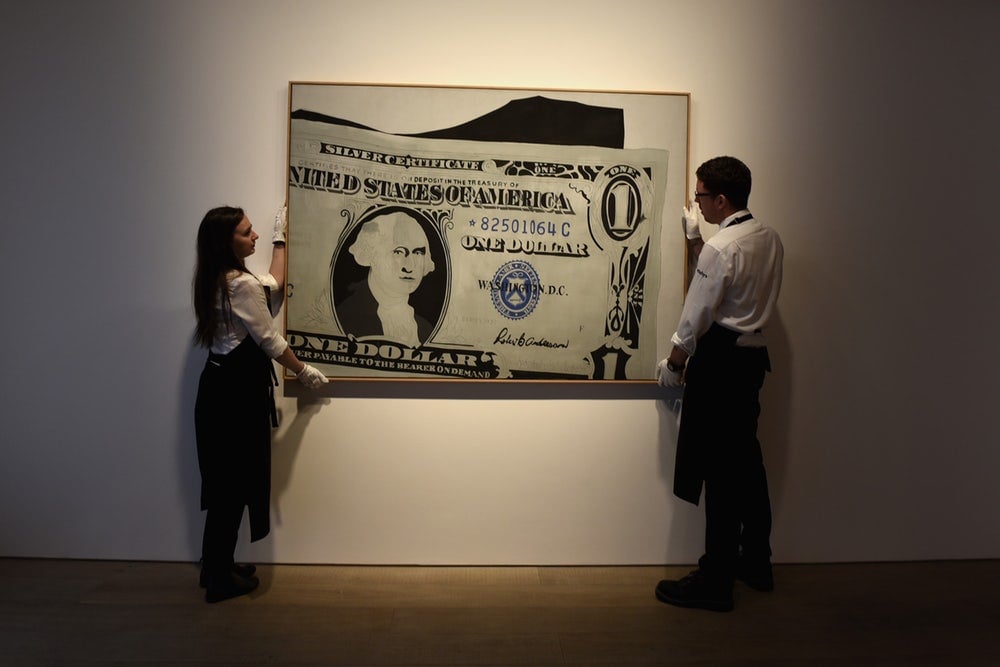

Andy Warhol’s signed dollar bill ahead of auction at Sotheby’s. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Before long, however, Schrader found that there were more similarities between finance and the auction business than he initially thought. “I was taking the view that the client is first, which is something I always had on Wall Street,” he said. “Not trying to make onetime sales, making long-term relationships. Coming to a place like Sotheby’s, and coming from institutions like J.P. Morgan, there’s a sort of corporate culture that I was used to—and it was just entrepreneurial.”

Less than a year in, Schrader had created an operation in which nearly 150 works consigned for private sale could be ready to view on York Avenue, without the hassle of shipping or publicity or printing catalogues. In 2017, private sales rose 28 percent, to a total of $745 million, a four-year high. The numbers for 2018 were even better—Schrader’s fiefdom hit a whopping $1 billion in sales, up 37 percent. By contrast, Christie’s booked just $653.3 million in private sales that year. In mid-February, a rep for Sotheby’s informed me that private sales dipped, but ever so slightly, in 2019—the division’s gross was “approaching” $1 billion. (Now that auction-house storefronts are shuttered, private sales are reportedly up again.)

David Schrader. Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

“David is singular, and he has a financial acumen in excess of the average art-history major who comes to work at an auction house,” Cappellazzo said. “Obviously he’s very adept at business and negotiations.”

For his part, Schrader shares the top brass’s vision that the key to success, now and in the future, is the age-old financial tactic of diversifying assets. “We’re going from a pure auction house to being a purveyor of luxury objects,” he said. “A lot of different objects across lots of different categories and a lot of different geographies.”

But what is lost if the barbarians walk through the gate, and the bankers turn the auction houses into general emporiums of fancy stuff instead of places that invest in growing markets for undervalued artists, securing quality consignments, and making headlines with bellwether evening sales?

Paul Leong, an investment banker at Brookfield Financial, says that some financial types should consider entering the art world without trying to completely rewire it from inside. Leong himself is a collector of revered “artist’s artists” who show at beloved galleries such as Reena Spaulings Fine Art, Galerie Buchholz, and Freedman Fitzpatrick.

His Tribeca apartment is full of difficult works that would be surprising to see in any home but especially that of a Wall Street guy: an early video by Ian Cheng above the bed, a magnificent hanging sculpture by Kayode Ojo, and photographs by divisive artist Heji Shin. (He bought the Ojo from Lucas Casso, a former Goldman Sachs trader who founded the Berlin gallery Sweetwater in 2018.)

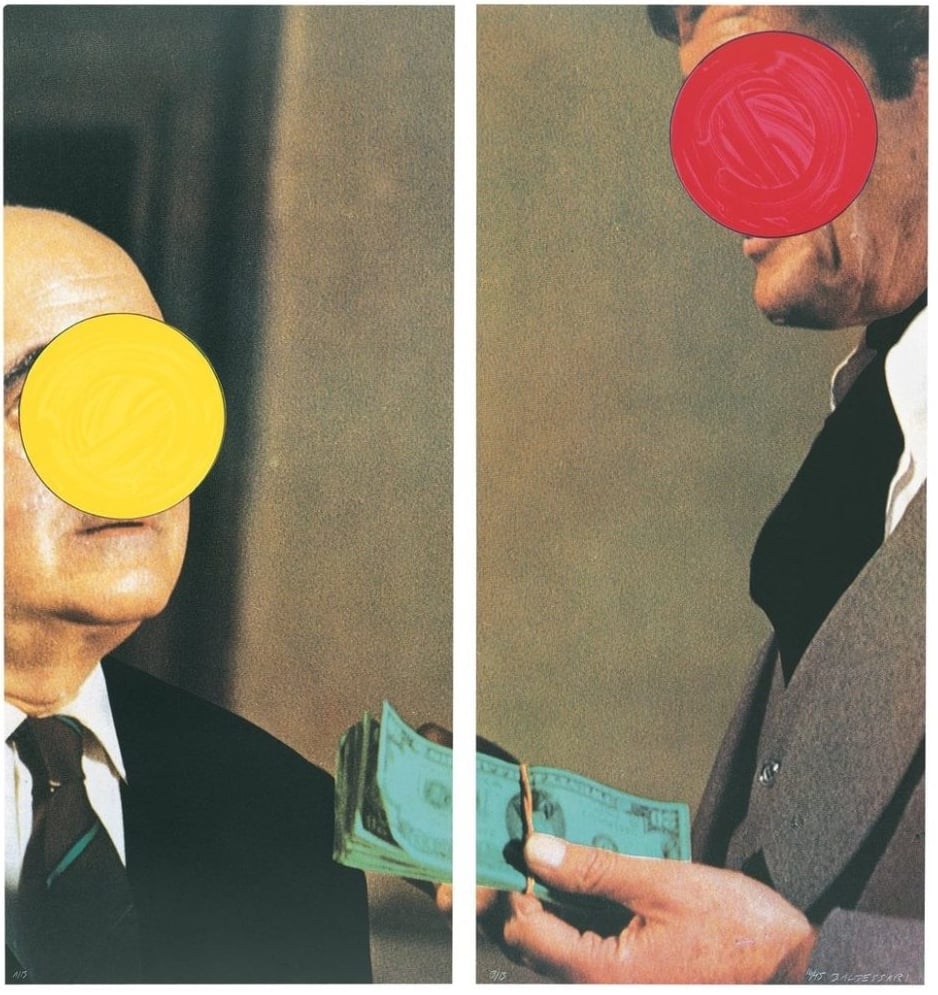

John Baldessari, Money (with Space Between), (1991) courtesy Gemini G.E.L.© John Baldessari.

When Leong started collecting, he approached the two ventures—financial trading and art buying—in a similar way. “A lot of people are surprised at how much research goes into collecting, and that definitely comes from being in finance,” Leong said.

He understands that, once his colleagues begin looking to collect in earnest, many will reach out to someone they feel comfortable with—like David Schrader.

“David worked in private banking and has a Rolodex,” Leong said. “I realize that he has different ways of thinking about what he’s doing in trying to grow the business, but it’s old school in the sense that it’s relationships and making sales.”

For her part, Cappellazzo—who, although she’s now an ace dealmaker, holds a master’s degree in urban design from the School of Architecture at Pratt Institute—told me, “I predict that you’ll see more people coming from banking looking at the art market.”

Even if Leong is one of the more curatorially minded bankers I’ve ever met, he thinks the financial world can benefit the art world by propping up the museums that can’t afford serious contemporary masterpieces, tightening up the auction model, and safeguarding against blips in the strength of the market.

“I’m very intrigued about the possibilities of business and art,” Leong said. “I think that every year they get closer and closer. There’s going to be a convergence.”

A version of this story first appeared in the spring 2020 Artnet Intelligence Report. To download the full report, which has juicy details on how A.I. could transform the art industry, what art top collectors are buying (and why), and how a wunderkind art dealer swindled high-flying collectors, click here.