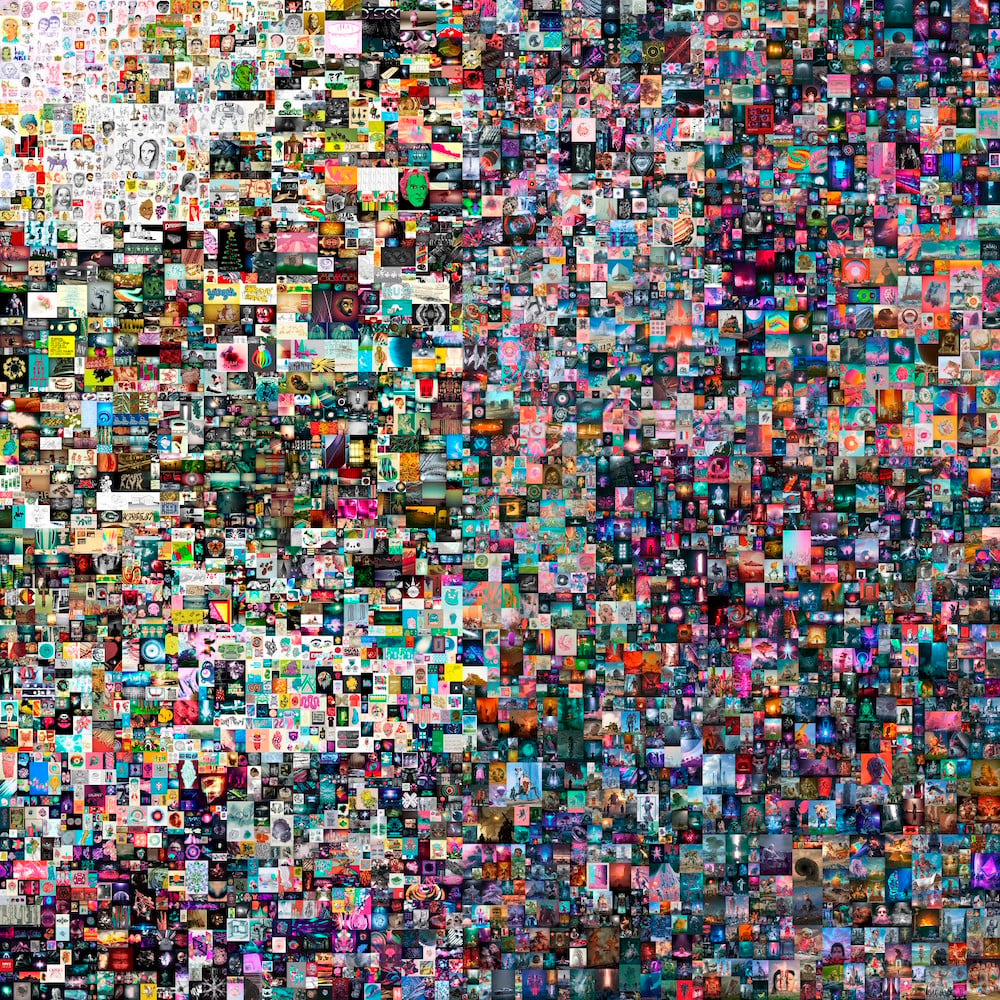

Beeple’s Everydays – The First 5,000 Days obliterated records and expectations when it sold at Christie’s for a hallucinatory $69.3 million on March 11.

But the piece, billed as the first “purely digital work with a unique NFT (non-fungible token)” to be sold by a major auction house, also cracked open a contentious debate about what, exactly, qualifies as an NFT, why those characteristics matter, and how much bearing they have on the pandemonium suddenly dominating the market for contemporary art and so much else.

The tension emerged shortly after a week of thunderous bidding for Everydays ended with a sonic boom last Thursday morning. Kelani Nichole, who first priced and sold artworks in bitcoin in 2013 as the owner of the new-media-centric Transfer Gallery, took to the private Discord server Friends With Benefits early that afternoon to call attention to what she saw as unusual behavior in the life cycle of Beeple’s headline-snatching token.

Based on what unfolded in the days after, both inside the chat and in the news cycle, she reached an unequivocal conclusion about Christie’s proclamation that it had made NFT history.

“It’s absurdity at every level of implementation,” she said. “They sold a JPEG. This was a $69 million marketing stunt.”

The chasm separating Nichole’s stance from Christie’s descends from two related issues. First, in technology as in art, specialists in the subject often define what something is based on how it is done. NFTs turn out to be a textbook example of this dynamic, as Nichole and other crypto-fluent observers judged that the way Christie’s conducted the sale of Everydays invalidated any claim to its being a non-fungible token.

This tension ratcheted up as the conversations on Friends With Benefits continued well into last Friday night, with multiple users expressing confusion over why, as one member put it, they saw “none of the usual stuff you’d expect to see” for an NFT sale through Etherscan, an established portal for viewing verified data on the Ethereum blockchain. (Blockchain is the broad technology that underlies NFT creation, tracking, and trading, with Ethereum being the specific blockchain that hosts the vast majority of the NFT market.)

But the second point of disagreement is even more existential. On one hand, Christie’s role in facilitating the sale of Beeple’s work was seen as a powerful validation of NFTs by (very) late adopters in the traditional art world. On the other hand, true believers in blockchain’s revolutionary potential aim to eliminate gatekeepers of all types. They saw Christie’s very presence in the sale as a betrayal of crypto’s core values, making any NFT transaction facilitated by the auction house illegitimate regardless of any procedural aspects.

At stake in this ideological clash are the answers to a set of questions equally relevant to the artistic avant-garde and techno-utopianists, particularly as demand for NFTs intensifies to nuclear levels. How many compromises can be made on an ideal before it implodes? Which dilutions (if any) are tolerable for the sake of attracting a larger audience to a potentially transformative cause? And will the answers be decided by any criteria other than who stands to make the most money from wide adoption?

Beeple, Everydays – Home Planet (Day 4,662) (2020). Courtesy of UCCA Beijing.

We Are What We Do

In one sense, selling an NFT is similar to selling a painting, sculpture, or any other traditional artwork on the primary market. But from a crypto purist’s perspective, the differences elevate NFTs to a higher plane of equity and transparency—assuming they are executed within specific guidelines. Deviate from those guidelines and the process drags the artwork back down into the same swamp that hides so many dubious dealings in the legacy art trade.

An NFT sale consists of three steps. First, the artist “mints” an NFT for their artwork on the blockchain, meaning they essentially register the piece, verify themselves as its maker, and confirm its status as either a unique or limited-edition digital asset.

Crucially, the NFT itself is merely a string of alphanumeric characters that identifies the artwork within the larger system of the blockchain, just as an inventory number identifies a particular painting in a gallery’s database. In the vast majority of cases, the token links to but does not actually include the piece, which is a discrete file hosted “off-chain” on another server.

For comparison’s sake, minting an NFT isn’t quite identical to an artist sending a digital photo of a new painting to a dealer to confirm authorship, integrate the piece into their inventory, and begin drawing interest from collectors… but it’s not terribly far off, either.

This leads to the second step: the artist makes the NFT available for direct sale through a particular intermediary. But whereas a traditional artist’s intermediary would normally be a dealer, the intermediary for an NFT is generally an online marketplace platform (such as MakersPlace, Christie’s partner in the Beeple sale). The NFT artist completes this step by authorizing their chosen platform to execute the blockchain-based “smart contract” governing the token’s terms and conditions.

Among those conditions are the terms of sale. Traditional artists and dealers reach this consensus manually through consignment agreements that specify asking prices, maximum allowable discounts, and the dealer’s share of sales proceeds on the new works.

One vital difference with NFTs, however, is that these terms are hard-coded into the smart contract. This means the final step in the sale—payment to the artist and transfer of ownership to the buyer—can happen automatically and nearly instantaneously. The process is much more laborious in the traditional market, where a dealer must manually send an invoice to a buyer, collect a check or wire transfers from that buyer, ship the artwork once payment has been made in full, and send the artist their cut.

Beyond the efficiency of automation, NFTs can also embed an artist resale royalty to be automatically paid out anytime the token is resold in perpetuity. Yet this advantage only manifests if the resale is executed via smart contract, i.e. through a marketplace platform. (While the standard NFT smart contract, known as ERC-721, does not include a built-in resale royalty, almost all platforms provide one in their own terms of service.)

Flip an NFT off-chain, however—say, through a dealer or auction house—and the artist risks losing any guaranteed resale proceeds they would have enjoyed in an on-chain transaction. This is especially unwelcome news for artists in the US, which has never awarded a resale royalty right, save for California in the lone year of 1978.

Most important of all, what separates an NFT sale from a painting sale is that each of the steps above is instantly documented, time-stamped, and reviewable by any interested party—not just the artist and buyer—as a discrete transaction on the blockchain.

In theory, this engenders confidence in the system even absent trust in its individual participants. The technology thus attempts to bridge the gap normally bridged by personal reputation and/or objective credentials in numerous fields.

Yet confidence in the Everydays sale was precisely what Nichole and several other Friends With Benefit members were lacking after repeated audits of the Ethereum blockchain. Still unaccounted for circa 10 p.m. EST last Friday, roughly 36 hours after Christie’s publicized the bombastic results, were verified transactions documenting two of the three steps needed to legitimize the sale of the NFT: the token being connected to the MakersPlace platform, and ownership being conveyed to the buyer.

Instead, the only component then visible on the blockchain was the same one that had existed for more than three weeks: Beeple’s minting of the Everydays token, including the accompanying link to a JPG of the artwork off-chain.

Jussi Pylkkanen. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

Ancestral Clash

Since its emergence as a concept in 2008, blockchain technology generated excitement for its theoretical power to establish “trustless” networks of economic, cultural, and societal exchange. If the concept proved out, hardware and software could equitably replace a wide range of centralized authorities (banks, courts of law, and governments) wielding tremendous power and, too often, questionable influence over modern life.

Art-market gatekeepers were soon added to the list. At Rhizome’s Seven on Seven summit in 2014, the artist Kevin McCoy (with collaborator Anil Dash) pioneered NFTs as a tool empowering artists to bypass dealers and directly monetize the distribution of their own digital artworks. McCoy later expanded the idea into an NFT platform called Monegraph as part of the New Museum’s New Inc. accelerator. (Monegraph ceased operating a few years later.)

This backstory clarifies why Christie’s role in the Beeple sale could rankle crypto purists regardless of whatever came next. It would be difficult to conjure a more potent symbol of the legacy art market and its reliance on influential intermediaries than one of the oldest and largest auction houses on the planet. Why pay a fee to insert a classic art-market middleman into an NFT sale, when NFTs were engineered in large part to eliminate dependence on middlemen?

The execution of the sale also crystallized the awkwardness of attempting to integrate the radical potential of NFTs with centuries-old market structures. Instead of playing out on MakersPlace, where all activity would be verified and archived on the blockchain to satisfy even the most discriminating crypto advocates, Christie’s announced that the bidding for Everydays would instead take place via the same online interface the house uses for its auctions of all other artworks and collectibles.

It was a galling decision to blockchain originalists. Where was the transparency and accountability if the competition for the token would all unfold off-chain? Even if you begrudgingly accepted Christie’s presence, how could their old-school process legitimize an actual NFT sale?

Christie’s publicized the (pseudonymous) identities of Everydays’s buyers, known as Metakovan and Twobadour, roughly one day after the weeklong auction concluded. The house also confirmed they paid in full using the cryptocurrency Ether. Had the sale taken place on-chain, the smart contract would have automatically conveyed ownership of the token to Metakovan moments after the full amount had been sent to Beeple.

But since Christie’s facilitated the auction and payment off-chain, the remaining steps in the NFT sale took place manually. This led to a lag in the transaction sequence, accounting for why Nichole and others could not find verification of anything but the nearly month-old minting of the Everydays token by 10 p.m. ET Friday.

The blockchain eventually memorialized Beeple transferring ownership of the token to a MakersPlace escrow account at 10:58 p.m. ET last Friday—the second step in the sale process that permits the platform to execute the smart contract—followed by a final transfer from MakersPlace to Metakovan at 12:16 a.m. ET Saturday.

Only at that point—roughly 38 hours after the virtual hammer came down at Christie’s—was the NFT sale for Everydays technically complete. Lightning-fast by traditional art-market standards, but lava-slow by hard-line crypto standards.

Beeple’s “Beeple Everydays: The 2020 Collection.” Courtesy of Metapurse.

Identity Crisis?

This chain of events begs the question: Should Everydays be considered the first NFT sold by a major auction house? It depends on whom you ask.

From Nichole’s perspective, the answer remains clear.

“Absolutely not,” she said. “The most celebrated characteristics of ERC-721 smart contracts in the context of ‘digital art’ are on-chain transparency, direct artist-to-buyer relationships, and the promise of artist resale rights in perpetuity—none of these technical affordances are at play in the way this sale was executed, precisely because these very qualities make Christie’s obsolete.”

Addie Wagenknecht, an artist and developer deeply engaged with blockchain, largely echoed Nichole’s thoughts: “My opinion is that it’s a PR event that Christie’s took on as an opportunity to leverage attention.”

Wagenknecht mentioned that a popular rumor in crypto-art circles last weekend was that the house had pre-sold the work before the auction began, rendering everything after as nothing more than the same kind of theater that in-person sales have so often become in the age of financial guarantees and irrevocable third-party bids. Likely contributing to this narrative was a tweet by crypto-entrepreneur Justin Sun, in which he alleged that his $70 million bid for the Everydays NFT was “somehow not accepted by Christie’s system” despite being submitted with 30 seconds to spare in the timed auction.

While a number of potentially legitimate rejoinders to Sun’s claim exist (such as the prospect that his bid simply did not reach Christie’s system before the lot closed), the narrative can take root easier thanks to the way the sale was conducted. The more components of an NFT transaction that happen off-chain, the more opportunities arise for self-interested parties to hammer out the same types of ethically murky backroom deals that have long defined the high-end art market—to the repulsion of the artistic and hacker avant-garde alike.

Christie’s, however, says Beeple’s work still qualifies as a non-fungible token.

“The elements that make it an NFT are the uniquely encrypted entity, incapable of duplication, that a digital asset becomes once minted, as well as its distinctive placement on the blockchain assigned thereafter. The manner of transaction should not impact its classification so long as the final transactions are recorded on the blockchain.”

McCoy, the artist who cofounded the Monegraph platform, similarly sees no problem. “This is certainly not a non-custodial transfer, which is typically how NFT marketplaces work,” he said. But “it’s still an NFT once it’s minted.”

In his view, it is just as legitimate to manually execute the remaining steps in an NFT sale as it is to automate them on-chain through the marketplace’s software. Since there is no dispute that Beeple minted a MakersPlace MKT2 token for Everydays in February, he feels the key condition has been satisfied.

McCoy approves of another aspect of Christie’s argument, too. The house’s spokesperson noted that “several marketplaces are moving an increased number of transactions off of the blockchain and onto their platform for sustainability purposes”—a reference to the well-documented ecological toll taken by proof-of-work blockchains including Ethereum.

McCoy attested to “an emergence of off-chain, near-chain, or delayed-chain transactions” that are often referred to as “lazy minting.” While he framed the primary advantages as lower costs and greater practicality, he confirmed that by deferring the remaining on-chain transactions until an NFT has actually been purchased, these alternatives do at least modestly reduce environmental impact.

Whether or not Everydays qualifies as a “true” NFT by the standards of blockchain originalists, however, it is undoubtedly now the shiniest token (figuratively speaking) of conspicuous consumption in what has become an all-consuming market frenzy. To many buyers with excess crypto wealth, that will be the only criterion that matters in judging Christie’s claims of making history. But long after this sale recedes from the headlines, the deep philosophical divisions it has exposed within the crypto-art community will persist—and should be remembered.