Auctions

Activists Gather for a Gloomy Vigil Outside of Sotheby’s to Protest First Sale of Berkshire Museum Works

"It's divided the community, and this whole thing could have been avoided," said group representative Hope Davis.

"It's divided the community, and this whole thing could have been avoided," said group representative Hope Davis.

Caroline Goldstein

For a group of Pittsfield residents, by the time Sotheby’s star lot, a $157 nude by Amedeo Modigliani, hit the block at its Impressionist and Modern sale last night, the evening’s excitement was long over.

The group was a contingent from Save the Art–Save the Museum, a grassroots organization based in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, which has led the charge in opposing the Berkshire Museum’s controversial plan to sell off 40 artworks to shore up its finances and fund a new direction for the institution. After a protracted legal battle, a judge finally cleared the way for the sale last month.

Monday night’s protest marked the first two artworks to be deaccessioned from the trove: a charcoal drawing by Henry Moore that fetched $300,000 (well below its pre-sale estimate of $400,000–600,000) and a 1914 painting by Francis Picabia that sold for $1.1 million, just below its high estimate of $800,000 to $1.2 million. The remaining lots will be sold over the next week, culminating with Sotheby’s American art sale on May 23.

About 20 members from the advocacy group Save the Art–Save the Museum gathered an hour before the auction for a somber demonstration. (They had alerted Sotheby’s in advance and received permission to protest.) This is not the first time the group has picketed outside of the Upper East Side auction house, though at this point there is no question that the sales will proceed.

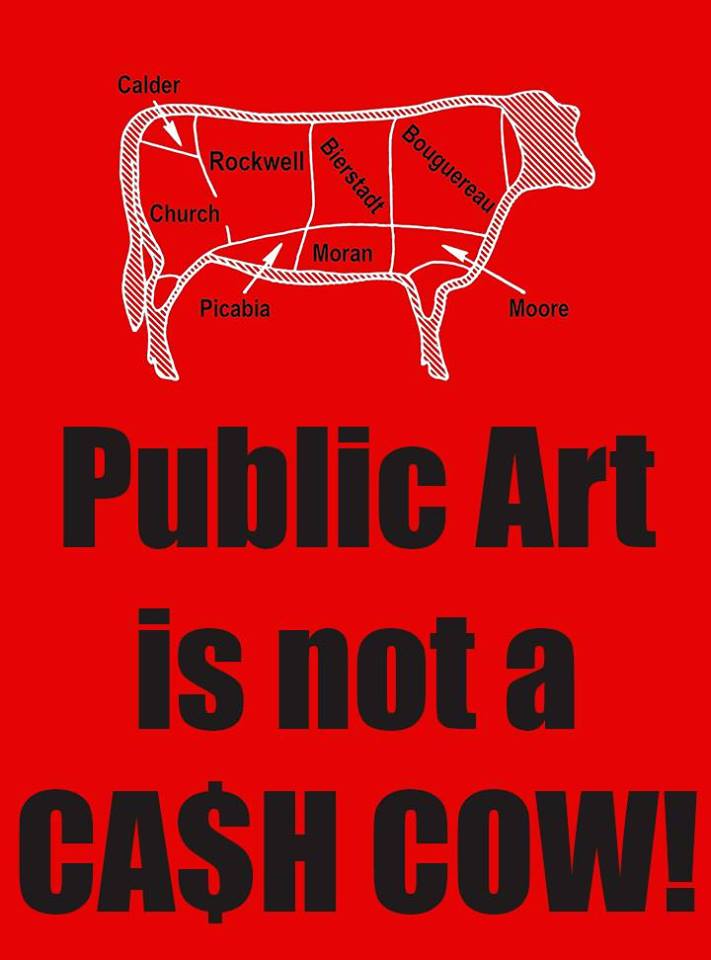

The demonstrators—one of whom brought her son and grandson to represent three generations of Berkshire denizens—stood quietly outside holding red signs with black lettering that read, “Public art is not a cash cow” and “Is your museum next?”

The group’s spokesperson, art advisor Hope Davis, told artnet News that the sale itself “is not the focus of our interests and it’s not why we’re here. We’re here to make a statement, nationally, that unethical deaccessioning is wrong. We are here to make the public aware of this precedent-setting initiative; we want the public to know that this is what could happen when a museum decides to monetize its collection.”

Left: Henry Moore’s Three Seated Women (1942). Right: Francis Picabia’s Force comique (1914). ©2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS). New York/ ADAGP, Paris.

There is some debate about whether the public protest could cast a negative light on the works, adversely affecting their price. In April, Christie’s New York held a sale of works from the La Salle University Art Museum in the wake of a brief but similarly contentious public fight over the decision to monetize the collection. Of the 22 works on offer, seven failed to sell; the remaining works netted a sum just below the house’s low estimate (including buyer’s premium).

Davis is aware that a similar situation could arise with the Berkshire Museum works—which, in this case, could pose an even bigger problem. Under the terms of the Massachusetts court’s ruling, the museum’s original batch of 40 works have been divided into groups. If the proceeds generated from the first tranche reaches the $55 million cap, the leftover artworks will not be sold and will remain in the museum’s collection. (Ironically, then, Save the Art is in an odd position; they oppose the sale but, now that it is in process, must invariably hope the works perform well.)

The deaccession that drew the most ire from community activists was Norman Rockwell’s 1959 painting Shuffleton’s Barbershop. But in the eleventh hour, as part of the final deal, the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art announced that it would pony up to acquire the work privately. The final purchase price was estimated at around $25 million. Davis, who specializes in American art, said the forthcoming Lucas Museum was the best place for the painting to remain in the public domain.

Image courtesy of Save the Art-Save the Museum.

A spokesman for Sotheby’s did not immediately respond to a request for comment about the demonstration. But the group may reunite for a final public appeal when Norman Rockwell’s Blacksmith’s Boy-Heel and Toe (1940), estimated at $7 to $10 million, and Frederic Edwin Church’s Valley of Santa Isabel, New Granada (1875), estimated at $5 to $7 million, are sold at Sotheby’s on May 23.