Art Fairs

5 Outstanding Works at Frieze London, From a Gripping Painting by Thornton Dial to Some Unsettling Photos by Cindy Sherman

Our handy guide will help you find the cream of the crop at this year's event.

Our handy guide will help you find the cream of the crop at this year's event.

Andrew Goldstein

Protests are raging in Hong Kong, fake blood is being sprayed around London by Extinction Rebellion, and Donald Trump keeps asking foreign governments to investigate his political rivals, even as Congress impeachment dangles above him.

In other words, all is normal on planet Earth in the year 2019—or at least as normal as we have come to expect it to be, with chaos being the only constant.

That paradoxical sense of unperturbed calm pervaded Frieze London, where, despite some freaked-out signage around the VIP entryway that nodded at the havoc raging outside the tent, the fair was absolutely business as usual.

Why not enjoy it while it lasts? Here are a few of the most intriguing art experiences to be found in the aisles.

Lia Rumma’s booth at Frieze London, curated by Joseph Kosuth. Courtesy of Lia Rumma.

The Frieze Art Fair’s brand rests upon its presentation of art commerce in a thoughtfully curated framework, and that not-always-easy-to-pull-off combination may have reached a pinnacle this year at the booth of Naples’s Lia Rumma Gallery, which assigned the job of assembling its wares to one of its artists, Joseph Kosuth.

Putting one’s business in the hands of an artist dedicated to interrogating the very nature and meaning of art may seem like a risky move, but the revered 74-year-old, Ohio-born Conceptualist evidently jumped in with both feet, producing an elegant, meditative display that nonetheless managed to make the artworks look very buyable.

Photos by Ugo Mulas and a neon by Joseph Kosuth.

Centered on a potted Japanese maple surrounded by white marble plaques—a piece by David Lamelas (€60,000)—the booth featured best-of hits by the gallery’s intellectual roster: a white wall piece by Haim Steinbach; a light gray painting by Ettore Spalletti; a suite of sensitive photographs of great postwar artists by Ugo Mulas (€7,500–18,000); a Pistoletto mirror with an ominously dangling noose (€600,000); an arrangement of medical scissors by Marzia Migliora responding to a pregnant-looking Gio Ponti pitcher; and art books by the Kabakovs and Giovanni Anselmo on individual shelves. Buzzing neons by Kosuth himself—one with a quote from Samuel Beckett, and the other from Gioachino Rossini (€80,000–90,000)—were perched atop the display to help set the mood.

The collaboration with Kosuth was so successful that the gallery plans to continue the approach in coming art fairs, handing booth-curating duties off to Alfredo Jaar for Artissima, Steinbach for Art Basel Miami Beach, and Spolletti for a fair next year. An even better idea? Some fair should create a whole section for artist-arranged booths.

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Kusum (1996).

An artist whose revelatory, just-closed show at the Met Breuer in New York drew rave reviews from critics—and wonderment that such a powerful artistic force could have remained under-known for so long—Mrinalini Mukherjee could be a case study in how marginalization can thwart a magnificent career.

Born in 1949 in Mumbai, Mukherjee grew up under the tutelage of artist parents and went on to study painting and mural design, but found herself drawn to working with woven fibers, creating imposingly sensual sculptures from dyed, knotted ropes that somehow manage to fuse Vedic deities with female genitalia. (Sometimes they look more like deities, sometimes genitalia; oftentimes, improbably, the works resemble both.)

Her peers in the predominantly male Mumbai art scene, unfortunately, had no idea what to do with her art. They saw it as gendered craft work, and dismissed her as a bit of an eccentric. As a result, she was never picked up into the slipstream of artistic discourse, which so frequently revolves around groups of artists, and which is critical for gaining the attention of curators and collectors.

Despite making some 200 of her woven sculptures—which she almost magically created without preparatory studies or drawings, relying instead on her intuitive understanding of knotted rope—she only received a museum retrospective in 2015, when her devoted longtime dealer Peter Nagy brought a hospital bed into the galleries of New Delhi’s National Gallery of Modern Art so she could oversee the installation in the weeks before she died.

Yet while that show and the Met Breuer survey have no doubt awaked curators to her work, the marketplace—where artists’ posthumous careers can get their wings, with historical value signaled through high prices at auction—doesn’t quite know what to do with her either. All of her fiber works are spoken for, and the only two that have ventured to auction fared unimpressively, one selling for $158,309 at Sotheby’s in 2014 and the other failing to elicit a bid in 2007. (Her less significant bronze and ceramic works, meanwhile, have sold at auction, but always in the $10,000 range.) The value of the woven sculpture that Nature Morte brought to Frieze can only be guesstimated, in the mid-to-high six figures—and even so, it is on loan from a private collection and is not for sale. In other words, it’s up to you, curators.

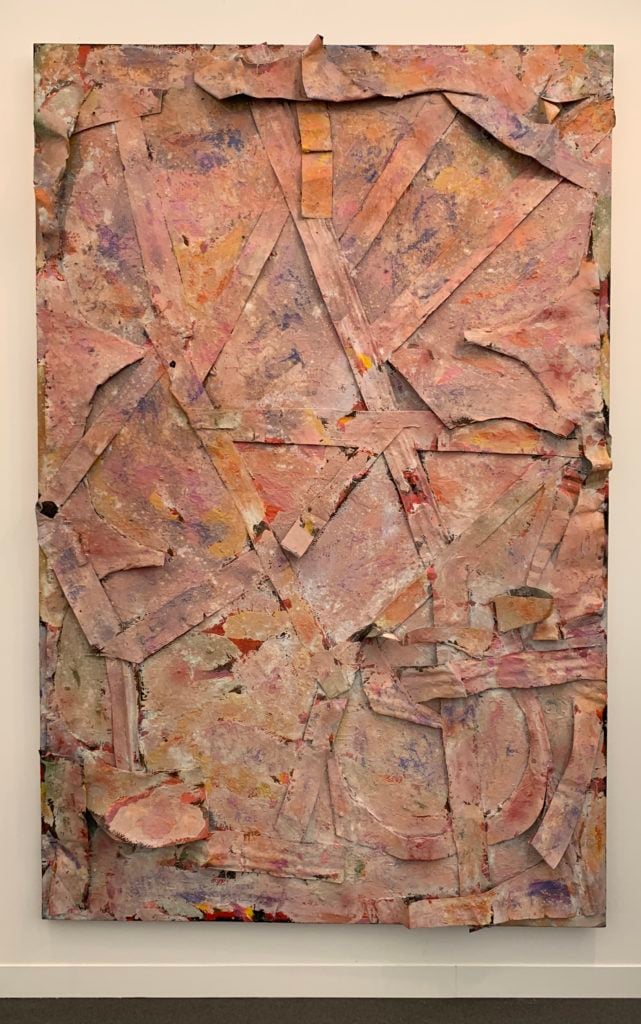

Thornton Dial, A Piece of Art (2004).

In the art world, context is key, and moving an artist from one context to another can be as effortful a process as breaking down and then reconstructing a home.

Such is the process underway with the late African American artist Thornton Dial. A towering self-taught talent who grew up illiterate in Alabama, and whose jobs included picking cotton and doing metalwork, he found a voice in his later years as an “outsider artist,” and was championed and grouped alongside artists such as Henry Darger and Adolf Wölfli, who worked in their own worlds, divorced from society, often making their art in mental institutions. (His New York Times obituary, when he died at 87 in 2016, labeled him an “Outsider Artist Whose Work Told of Black Life.”)

But Dial was hardly an outsider artist, says David Lewis, the young Lower East Side art dealer who has been working with the artist’s family for about two years. Instead, he was keenly aware of art history, making work that was consciously in dialogue with other art—something that is reflected in such paintings as the surpassingly delicate-looking painting of sculpted tin, gypsum powder, and enamel Lewis brought to Frieze, which he said was inspired by a Joan Mitchell painting.

Lucy Dodd’s Sun Dial (2019) next to the Thornton Dial painting.

Recently this view of Dial as an artist actively involved in the art of his time has been embraced by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which, since receiving the gift of dozens of his paintings from Will Arnett’s Souls Grown Deep Foundation in 2014, has been displaying his work side-by-side with Rauschenbergs and Jasper Johnses.

Now, however, Lewis wants to shift Dial’s context even further, framing him as a lively contemporary artist. In the fair, Dial’s painting is displayed together with brand-new Lucy Dodd canvas, Sun Dial (2019), that was made deliberately in response to the late artist’s work, and also incorporates elements of Mitchell’s style. The dealer also notes, with approval, that a recent buyer of a Dial work took down an Elizabeth Peyton painting to make room for the canvas, which now hangs opposite a John Currin.

These context changes are happening amid broader transformations in the art landscape as large, which have led to a restructuring of art history to make its past and future more inclusive. “The first step was to get his work into the canon,” Lewis says of Dial. “Now a new generation is saying that, not only is Dial in the canon, but he’s the bedrock of what the canon will become.”

Works from Cindy Sherman’s “Broken Dolls” series.

No, these are not unrated outtakes from the latest Toy Story movie, but rather photographs from Cindy Sherman’s “Broken Dolls” series, an important chapter of the artist’s ever-evolving career.

Where do these fit into her overall oeuvre? A quick recap: Sherman came to prominence in the 1970s with her black-and-white “Film Still” self-portraits, then transitioned to her market-dominating full-color “Centerfolds” series, and then, in the late 1980s, she entered her uncanny period—a decade-long chapter when she took herself out of the frame and instead made series after series of raw, disturbing photographs of dolls, masks, and prosthetics that seemed plucked from Dr. Freud’s nightmares.

This period, which fascinates her most devoted admirers and repels those who prize her earlier cinematic portraits, culminates in the “Broken Dolls” works, in which naked girls’ toys have been tortured, mutilated, and otherwise abused and photographed in black and white, evoking the Surrealist work of Hans Bellmer while also possibly signifying Sherman’s anger at the conservative, repressive climate of America at the time. With this series, Sherman got something out of her system, because in 2000 she returned to featuring herself in her photographs and has been doing so ever since.

Twenty years later, the doll images still shock. Will they ever be treated as masterpieces by the art market (which even goes gaga for Sherman’s terrifying clown self-portraits)? Or will they linger on as a restive provocation, haunting the more collectible, more pleasurable facets of her career?

Martine Syms, Capricorn (2019).

Martine Syms, the 31-year-old, self-described “conceptual entrepreneur,” whose complex and often biting video installations about identity and race have graced the Whitney Biennial and other major shows, may have made her most commercial work yet with her new video at Frieze. And that’s “commercial” in both senses of the word.

The artwork, a loop of 100-second-long (i.e., TV-commercial-long) videos, plays like an Impressionist, amalgamated remix of Nike ads featuring black athletes. The protagonist—or avatar—is played by a young black dancer who approaches the artificial green of a driving range on which she proceeds to jerkily dance, using it like a prop in a music video. She occasionally stops dancing and hacks at the golf ball, and sometimes hits extraordinarily good shots.

Every so often, the camera zooms in for a closeup of her sweaty, intense, pensive face—an image that looks readymade for a billboard if you just add a little swoosh in the corner. According to the gallery, the video is an homage (of sorts) to Venus Williams, Florence Griffith Joyner, and other black female athletes, and how they are represented in popular culture.

Martine Syms, Capricorn (2019).

As for that other sense of commercial, the work is just beautifully packaged.

Syms had a custom TV created specifically for the video, and it’s a perfectly sleek black box that is almost as absorbing to look at as the video itself. In fact, it might be the nicest-looking video-art-playing device I’ve ever seen—it makes you just kind of want it.

Considering that Syms’s career is continuing to rise, with the artist having now received the second Future Fields Commission in Time-Based Media from the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the combination of her timely art and her stylish presentation might actually make video art pay off financially, as well as reputationally.