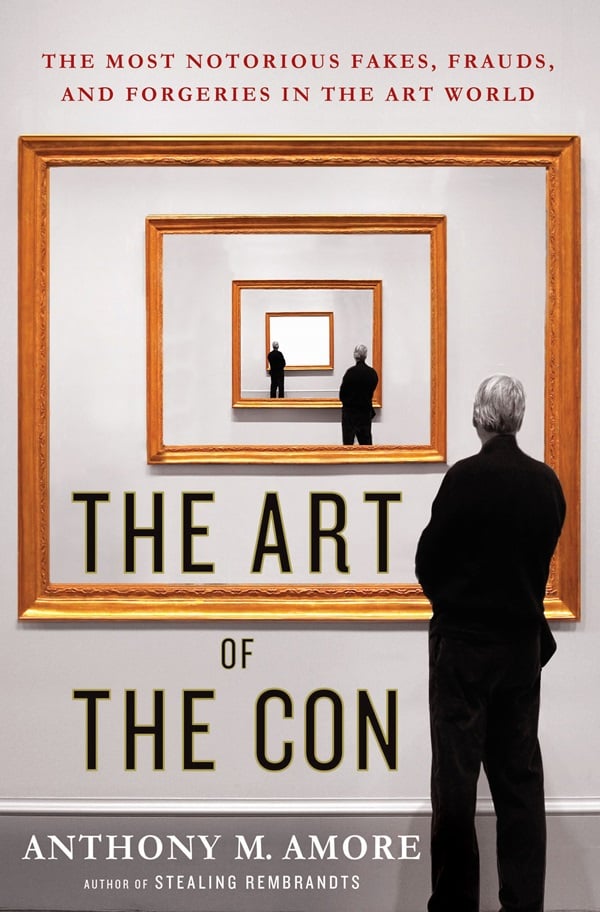

In his new book, The Art of The Con, Anthony Amore gives a fascinating account of some of the biggest scams that have taken place in the art world over the last century.

Amore, a security expert who is the chief investigator at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, gives the who, what, where, why—and perhaps most importantly—the how, behind some of the most incredible tales of fakes, forgeries, thefts and art-related ponzi schemes.

For anyone who has ever shook their head in utter disbelief about the ability of a con artist to dupe an intelligent person into believing—and buying—a fake work on a tall tale, Amore gives insight into how easily and frequently it can happen.

By focusing each chapter on a particular individual or element of an art crime—The Forger, The Broker, The Trusting Artist, The Double Dealer, The Telescam—the author explores the different ways that art fraud is perpetrated. Tales range from expert forgers to charming salesmen, unethical behavior by artist assistants, and the often thorny issues related to art recovery services.

He also lays out the elaborate art Ponzi scheme perpetrated by the now-imprisoned dealer Larry Salander, who frequently sold the same painting or shares of a work to multiple people, in a passage about con artists (below). The fallout from that case is still being felt in the art world.

Con men…are successful because of their ability to find marks—specifically, those in whom they can sense a strong desire to believe, against all indications to the contrary, that they have actually stumbled upon the rare deal that is both too good and true. And a key component of the scammer’s ruse is the development of a strong backstory to explain how he came into possession of such valuable art. When it comes to phony art, the con man will typically develop a story that involves a collection that had been hidden away for years, perhaps by a relative who has just died.

This was precisely the case with the Knoedler scandal, where a wild backstory of a secretive “Mr. X” and his son “Mr. X Jr.” and their multimillion dollar collection of Abstract Expressionist masterpieces was further validated by the once prestigious gallery’s willingness to accept the “story” and broker deals for such works.

Following extensive forensic testing—which in most cases showed serious problems with the materials used to create the works—investigators finally found the smoking gun, a skilled Chinese artist working in Queens, New York, who was paid nominal sums to custom paint works that were then sold for tens of millions of dollars. The painter has since fled the country and there are numerous civil lawsuits pending against the now shuttered gallery and its former president Ann Freedman, who brokered many of the sales.

Amore also includes some lesser known cases that indicate art fraud is nothing new. The book opens with the tale of Captain John E. Swords, a 19th century Philadelphia-based merchant who convinced renowned portraitist Gilbert Stuart, to paint a portrait of George Washington, with the promise that he would not duplicate it. Having convinced Stuart he intended to gift the portrait to a gentleman in Virginia, Swords promptly sailed to Guangzhou, China, where he had skilled copyists produce one hundred more versions.

Upon his return to the US, Swords found dozens of eager buyers. At the time, the market for Chinese-made goods was robust. In the book, When America First Met China, Eric Jay Dolin writes that “by one estimate as much as one-tenth to one-fifth of all the items in many 19th century homes” in several East Coast cities had items from China.

When word of this inevitably got back to Stuart, he sued Swords, winning a court order forcing the captain to halt sales and hand over the remaining copies.

In a subsequent chapter called “The Bait and Switch,” Amore details a situation in which a dealer commissioned an exact copy of a work by Pablo Picasso that she then passed off and sold as authentic. The author explains how the devil is truly in the details when it comes to many of these cases. A Picasso expert realized something was amiss when he saw, among other inconsistencies, identical signatures on the works in a side-by-side comparison. They were created at a time when the artist’s signatures “varied considerably,” as Amore writes.

As Picasso once said, “It is not enough to know an artist’s works. One must also know when he did them, why, how, in what circumstances…I attempt to leave as complete a documentation as possible for posterity.”

Related Stories

Knoedler Forger Misspelled Pollock

Will Larry Salander’s Fraud Victims Get Their Money Back?

Rare Stolen Duccio Painting Finally Coming to Auction