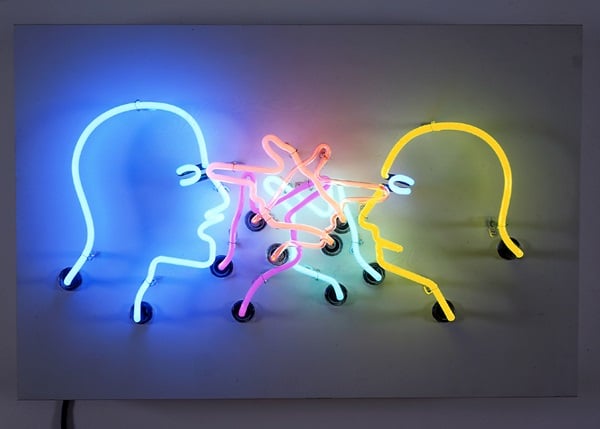

Bruce Nauman, Violins Violence Silence (1981/82).

This work sold for $4 million at Sotheby’s New York in 2009, the second highest auction price for Nauman.

Image: Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Bruce Nauman is considered a towering and influential figure in postwar American art. His reputation as a master of minimalist and conceptual art was cemented more than four decades ago when he was first showing with Leo Castelli in New York and in important European shows like “When Attitudes Become Form,” at the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland.

Currently, Nauman’s neons—paired with Adel Abdessemed’s machete sculptures—make an ominous opening to the main exhibition of the 56th Venice Biennale, “All the World’s Futures,” curated by Okwui Enwezor. The Museum of Modern Art in New York recently announced it will stage a full retrospective of Nauman’s work in conjunction with the Schaulager in Basel, Switzerland. The show, which will be the first comprehensive retrospective of the artist’s work across all mediums in over 20 years, will travel to MoMA in September 2018.

This past April, we were somewhat surprised to see Nauman’s name on artnet News’s list of the 10 Most Expensive Living American Artists, alongside some of the more obvious suspects like Jeff Koons, Jasper Johns, and Christopher Wool (Nauman didn’t make this year’s list). For all the respect and attention given to Nauman and his work, he is not exactly the type of eight-figure fixture at auction that his contemporaries are.

Auction values for Bruce Nauman (1986–2015).

Image: Courtesy of artnet Analytics

“Bruce Nauman’s work is not what trophy hunters go after in the way they might go after work by Christopher Wool, Takashi Murakami, or Richard Prince,” explains Nauman’s longtime dealer Angela Westwater, co-founder of Sperone Westwater, in a phone interview with artnet News. “No label fits him. The disparate body of work can include performance, photography, neon, drawing, sculpture in plaster, sculpture in wood, sculpture in bronze, sculpture in wax, video, and sound.”

Add to that the fact that many of his large-scale mixed media works are too ambitious for all but the most cavernous and deep-pocketed of institutions and collectors to buy and house.

The work that once placed Nauman among the most expensive artists is a playful 1967 plaster and wax sculpture, titled Henry Moore bound to fail (Back view) (1967), created from a photograph of Nauman’s back with his arms tied behind him. The work sold at Christie’s in May 2001 for $9.9 million, almost five times its low estimate of $2 million, and more than twice his next highest price achieved at auction—$4 million for the 2009 sale of one of his seminal neon works, Violins violence silence (1987).

Bruce Nauman, Henry Moore bound to fail (Back view) (1967).

This work holds the auction record for the artist. It sold for $9.9 million at Christie’s New York in 2001.

Image: Courtesy of Christie’s.

The artnet Price Database lists a total of 980 Nauman works that have come up at auction over the years. Fourteen have sold above $1 million each. About 240 pieces, or 24 percent, went unsold. The lowest price on record was $130 set for a 1975 editioned lithograph, Ah ha black and white, that sold in 1997 at Bukowskis in Stockholm, Sweden, far below the estimate of about $780-$1,000.

However, demand for major works has never been a problem, asserts Westwater. “Of the first shows we did, dating back in this gallery to about 1976, works were sold early on to museums, collectors, and institutions who still have them” including steel and plaster sculptures among them. Westwater easily rattles off some of the early buyers in the 1970s and 80s.

“I’m talking about the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, Anton Herbert in Belgium, the Emmanuel Hoffmann Foundation in Basel, Thomas Ammann bought sculpture early on, now in the Daros Collection,” she said. “In some ways, Nauman was better known in Europe than he was in the United States.”

Others, she said, went to US institutions including the Carnegie Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago as well as to collector Gerald Elliot who left many to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.

“The pieces that have come up for sale at auction have not been the largest nor necessarily the most important,” says Westwater. “Neons are pieces that people can accommodate more easily at home.”

Bruce Nauman, Double Poke In The Eye II (1985).

Image: Courtesy of Sperone Westwater Gallery.

“His recent large-scale videos are really more appropriate for museums since they often require whole rooms and very large walls in institutional spaces,” she says. “One indication of the rise in Bruce’s market has been the dramatic increase in the prices of three editioned works: one in neon from 1985 and two videos—one from 1985 and the other from 1999.”

These three works, each in an edition of 40, include: Double Poke in The Eye, a 1985 neon (one sold for $461,000 at Christie’s in November 2014); Good Boy Bad Boy (1985) a two-part video (one sold for $386,000 at Christie’s in 2011); and another video entitled Setting a Good Corner (1999), one of which sold for $146,500 at Christie’s New York in May 2009.

Prices have really jumped at auction and have been even higher when sold privately, Westwater said, adding that they have been acquired “by major private collections such as Glenstone, the Flick Collection, The Daskalopoulos Collection and the Froehlich Collection, and museums such as Tate, Kunstmuseum Basel, SFMoMA, the Whitney, Centre Georges Pompidou, and La Caixa.”

Nauman’s installation for the US pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 2009.

Image: Courtesy of Sperone Westwater.

Despite some of the quirks and limitations of this market, Westwater agrees that Nauman’s much-lauded representation of the US in the 2009 Venice Biennale, organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and even more recent shows such as the one at the Cartier Foundation in Paris this past winter, have really boosted his profile and made his work more accessible to broader audiences.

Writing in artnet Magazine in 2009, Ben Davis said of the Venice Biennale: “The U.S. presentation of Nauman—tightly focused but spread out over three locations throughout the city—blew everyone…away.” Nauman won the Golden Lion that year (he’s won it twice overall).

Nauman’s U.S. Pavilion at the 2009 Biennale, according to Westwater, “attracted and educated a large international audience.” Carlos Basualdo and Michael Taylor, who curated the exhibition for the Philadelphia Art Museum, organized the show around three provisional categories: Heads and Hands, Sound and Space, and Fountains and Neons. Works were grouped under these categories in three distinct exhibition sites—the Giardini and two universities. “I think the mix and kind of crossover was elucidating to many people.”

Installation view of Bruce Nauman’s recent major exhibition at the Cartier Foundation in Paris.

Image: Courtesy of Sperone Westwater Gallery.

Nauman had previously won the Golden Lion in 1999 for Lifetime Achievement, but this was not in conjunction with a large exhibition such as that 10 years later. The 2009 exhibition, Bruce Nauman: Topological Gardens, was awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation.

Another apparent milestone and revelation for even some longtime fans, was a show at the Jean Nouvel-designed Fondation Cartier this past March.

“For those who, like me, tend to find much of Nauman either too horrible or too tedious to bear—the video Clown Torture screaming “no”; the banal repetitions across a 60-minute film of Tony Sinking into the Floor, Face Up, and Face Down,” Financial Times critic Jackie Wullschlager wrote, “this exhibition is lifted to revelation by its setting. ”

Wullschlager went on to praise Nauman as a figure of towering impact on body art, conceptualism, minimalism, performance.

“Those Naumans in that building was totally like a breakthrough,” said Westwater summing up the show. “A Eureka moment.”

Related stories:

artnet News’s Top 10 Most Expensive Living American Artists

artnet News’s Top 10 Most Expensive Living American Artists 2015

MoMA Organizes Bruce Nauman Retrospective

Bruce Nauman Receives Friedrich Kriesler Prize