Auctions

A $28 Million T-Rex Skeleton Was the Undisputed King of Christie’s Otherwise Muted $341 Million Contemporary Art Auction

Christie's added a fair amount of theater to the hybrid event, including live commentary by two of its specialists.

Christie's added a fair amount of theater to the hybrid event, including live commentary by two of its specialists.

Eileen Kinsella

Christie’s 20th-century evening art auction, which included one major and notable non-art item (more on that below), was conducted via livestream from Rockefeller Center on Tuesday night, and realized $340.8 million, squarely in the middle of presale expectations of $277.3 million to $401.4 million. (Final prices include premiums; pre-sale estimates do not.)

Expectations were revised downward after four lots—including a heavily marketed Brice Marden painting titled The Golden Pelvic (1993–95) that was estimated to sell for $12 million to $18 million—were withdrawn just before the start of the sale.

Forty-six of the lots offered (86 percent of them) sold by lot; 96 percent sold by value, according to the auction house.

Auctioneer Adrien Meyer, chairman of global private sales, conducted the sale in a room full of specialists on phone banks. He also fielded phone bids from salesrooms in London and Hong Kong, and online via Christie’s website.

There was a fair amount of added theater, as specialists vied to convey some of the “in real life” tension that takes place in the auction room. Christie’s added an extra layer of atmosphere with the inclusion of elaborate set designs and background music that seemed aimed at filling in some of the pauses in bidding. Some specialists were even decked out in jewels to be featured in forthcoming auctions.

Stan, the T-Rex. Image courtesy Christie’s.

There was also the novelty of live commentary by two veteran specialists. Informative but low key, it seemed to work just fine, though there was an element of “golf” chatter to the proceedings.

Of the 55 lots on offer, 14 were guaranteed, including two that found backing immediately before the sale opened. In a sign of how third-party guarantors are often wheeling and dealing right up to the start of a sale, the number of third-party guarantees rose from eight to 10 earlier in the day.

Bidding was solid if rarely heated throughout most of the night, suggesting that buyers were clear on what they wanted and at what price. The cautious tone further underscored the need for securing guarantees on the selling side. Some experts suggested that the early-season date of the sale, well ahead of the usual November auctions, was what led to quieter bidding on presumed trophy lots.

Alex Rotter, head of the 20th- and 21st- century art teams at Christie’s, conceded that the timing of the sale was quite deliberate, considering the forthcoming US election and further potential health concerns this fall.

“Are we thinking about these things? Absolutely,” he said in a press conference following the sale, adding: “Obviously it works: 280,000 viewers and $340 million worth of sales. I’m good with that.”

The grand finale of the evening—the unprecedented auction of a T-Rex skeleton named “Stan” that carried an estimate of $6 million to $8 million—is likely to linger in everyone’s memory. Christie’s even brought out a separate auctioneer, Tash Perrin, to auction the lot, one of the largest and most complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeletons ever discovered. It was offered without a reserve or minimum.

After Perrin opened bidding at around $3 million, it was chased mostly by two Christie’s specialists up to the mid $20 million range. But their pursuit was interrupted periodically, and rather bizarrely at times, by Rotter, whose client sent the price several million dollars higher at several points, instead of sticking to the $500,000 increments the two other competitors were adhering to.

Paul Cézanne, Nature morte avec pot au lait, melon et sucrier (circa, 1900–06). Image courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd.

In the end, it was won by Christie’s specialist James Hislop, head of its science and natural history division. “Stan” hammered down for $27.5 million, and Hislop declined to say whether it sold to a private or institutional buyer.

Back in the fine-art realm, two of the highest-performing lots of the night were blue-chip trophies reportedly consigned by billionaire businessman Ronald Perelman, whose recent offloading of art and other major assets have the world wondering if he faces some dire financial situation.

Mark Rothko’s 1967 Untitled, a deep crimson painting with a $30 million to $50 million estimate, sold for $31.3 million with premium, just clearing its low estimate. It went to Christie’s deputy chairman for Asia, Xin Li. Given that the lot was also the subject of an 11th-hour third-party guarantee announced at the sale, there’s a good chance it went to the guarantor. The Rothko last sold at auction for $1.2 million in 1998, according to the Artnet Price Database. Perelman reportedly bought it privately in 2002.

Another top lot reportedly consigned by Perelman was Willem de Kooning’s Woman (Green) (1953–55), which was estimated between $20 million to $30 million, and sold for $23.3 million with premium. It hammered down to Rotter at the $20 million low estimate and did not have a guarantee.

All in all, it was not a bad day for Perelmen, whose major Gerhard Richter abstract painting garnered close to $28 million at a Sotheby’s Hong Kong sale of contemporary art earlier in the day.

Other top lots at Christie’s included Paul Cézanne’s watercolor, Nature morte avec pot au lait, melon et sucrier (1900–06), which sold for $28.6 million, a record for a work on paper by the artist, against an estimate “in the region of $25 million,” according to the auction house. The painting came from the collection of the late Edsel and Eleanor Ford and had the added allure of being featured in the first-ever show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1929. Edsel Ford acquired it in 1933.

It’s no secret that museum deaccessioning has been a hot-button issue in recent months, with some institutions opting to take advantage of relaxed Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) rules allowing sales of collection works to sustain museums in difficult times.

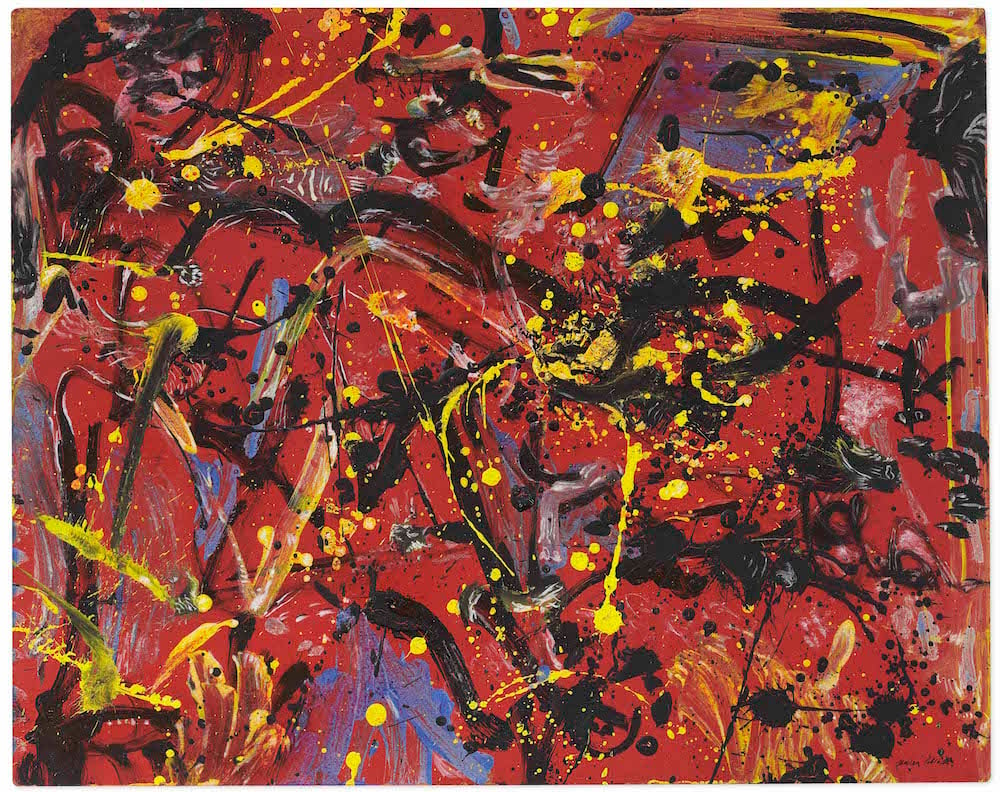

Jackson Pollock, Red Composition (1946). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Other museums are selling artworks for different purposes: the Everson Museum in Syracuse, New York, for example, sold off a major Jackson Pollock to fund its efforts to diversify its collection. Proceeds from the sale of the Pollock painting, Red Composition (1946), which was estimated at $12 million to $18 million, will fund acquisitions of artworks by artists of color, women, and others under-represented in the museum’s holdings.

After Meyer opened bidding at $9 million, it hammered down to a Christie’s specialist for $12 million, or $13 million with premium.

Another institutional seller was the Springfield Museum, which tellingly emphasized in the Christie’s catalogue that it was selling Pablo Picasso’s La Poule (1950), which went for $4.3 million, to support the care of its collection and to fund further acquisitions.