In contrast to the meek Sotheby’s sale that kicked off London’s auction season, Christie’s fielded what could have been its strongest-ever evening sale of Impressionist and Modern art in London this evening, with a massive pre-sale estimate of £179 million to £233 million ($238 million to $310 million), excluding premium and even after three lots were withdrawn. However, when the top lot, a Monet waterlily pond with a weeping willow estimated at £40 million, failed to sell, those ambitions were nipped in the bud. The sale eventually realized £165.7 million ($219.5 million) including premium, with 67 out of 82 lots sold. That still managed to be its second-highest total for an evening Impressionist sale in London, just short of the £176.9 million achieved in February 2014.

The very different picture drawn by this sale compared to Sotheby’s was due to Christie’s consignment of two single-owner collections—which, in turn, performed very differently.

The first, valued at over £100 million, was secured from America late last summer, when the New York sales were jam-packed with Rockefeller and other starry estate collections. Keith Gill of Christie’s said it made sense to sell it in London, “the most international center of the world,” rather than New York, where it would have created less of an impact. Designated as the property of an “Important Private Collection” that sourced its contents largely from such dealers as Wildenstein, Acquavella, and Lefevre in the ’80s and early ’90s, the works were consigned by a source undisclosed by Christie’s. But artnet News has learned that they came from Boston real estate developer Monte J. Wallace, whose family members are patrons of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Claude Monet’s Saule pleureur et bassin aux nympheas, 1916-1919, failed to sell. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

Sold without guarantees, the tranche was led by the Monet waterlily painting—a late work showing his pond at Giverny with a willow tree boldly occupying (some might say obscuring) the left side of the composition. A twist on the artist’s signature theme, it was purchased from Wildenstein in 1985 and had never been seen at auction, and the painting’s unpublished estimate of £40 million placed it in line with the purer waterlily painting Christie’s sold to Russian billionaire Andrey Melnichenko in 2008. But there were no bids on the picture. The Asian specialists on the telephone bank to whom the auctioneer, Jussi Pylkkanen, looked hopefully, were not even one their phones. Was it the inconvenient tree or the stamped signature? Probably both.

Another Monet, a fairly insipid painting of an Iris from the same collection (also with a stamped signature), was estimated at £4 million and also failed to sell. (Stamped signatures were applied to Monet’s paintings that remained in his studio, unsold, after his death).

Paul Cézanne’s Nature morte de pêches et poires, 1885-1887, sold for $28,094,969. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

The top-seller from the Wallace collection was a Cézanne still life of fruit on a table—not in the calibre of the $41.6 million example that sold at Sotheby’s in 2013, but good and rare enough to sell for £21 million ($28.1 million) to New York art advisor Nancy Whyte. It was last at auction in 1980, when it sold to Lefevre for $725,000.

More competition was seen for an early Impressionist landscape by Renoir, which exceeded estimates to sell for £12.7 million ($16.8 million) to an unidentified man in the salesroom taking bids on his cellphone. An unexceptional small Matisse portrait of a woman sold within estimate for £2.8 million ($3.73 million) to New York’s Acquavella Gallery, and a 1907 still life by Vlaminck—neither Fauve nor Cubist—sold to London advisory firm Beaumont Nathan within estimate for £2 million ($2.66 million).

Pablo Picasso’s Nature morte au crâne de taureau, 1942, sold for $6,288,781. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

Apart from the two Monets, the other big flop of the Wallace sale was a muddy Antwerp-period Van Gogh of a peasant woman, bought from Wildenstein in 1985 and overestimated at £8 million to £12 million. Pylkkanen was willing to sell at £5 million but got no response. A few lots later a Degas bronze of a dancer was allowed to sell for a half-estimate £112,500. The much-vaunted Wallace collection ended up realizing just half its pre-sale estimate to bring in £50.5 million ($67.2 million)—not a statistic Christie’s wanted to dwell on in its post-sale conference.

The second major collection on offer comprised works of better quality, and was mysteriously—if fulsomely—described as “An Adventurous Spirit: Masterpieces From an Important Private Collection Sold to Benefit a Charitable Foundation.” The owner, however, can be identified as the Canadian cable-TV billionaire David Graham, who owned properties from St. Barts to St. Tropez and from London to Toronto, and who died in 2017.

Edgar Degas’s Danseuses dans une salle d’exercice (Trois Danseuses), 1873, sold for $5,536,844. image courtesy of Christie’s.

Graham had a better eye for quality. Before he died, Graham sold a flower paining by Gustav Klimt for £48 million, and since his death Christie’s has been selling his furnishings and lower-value art.

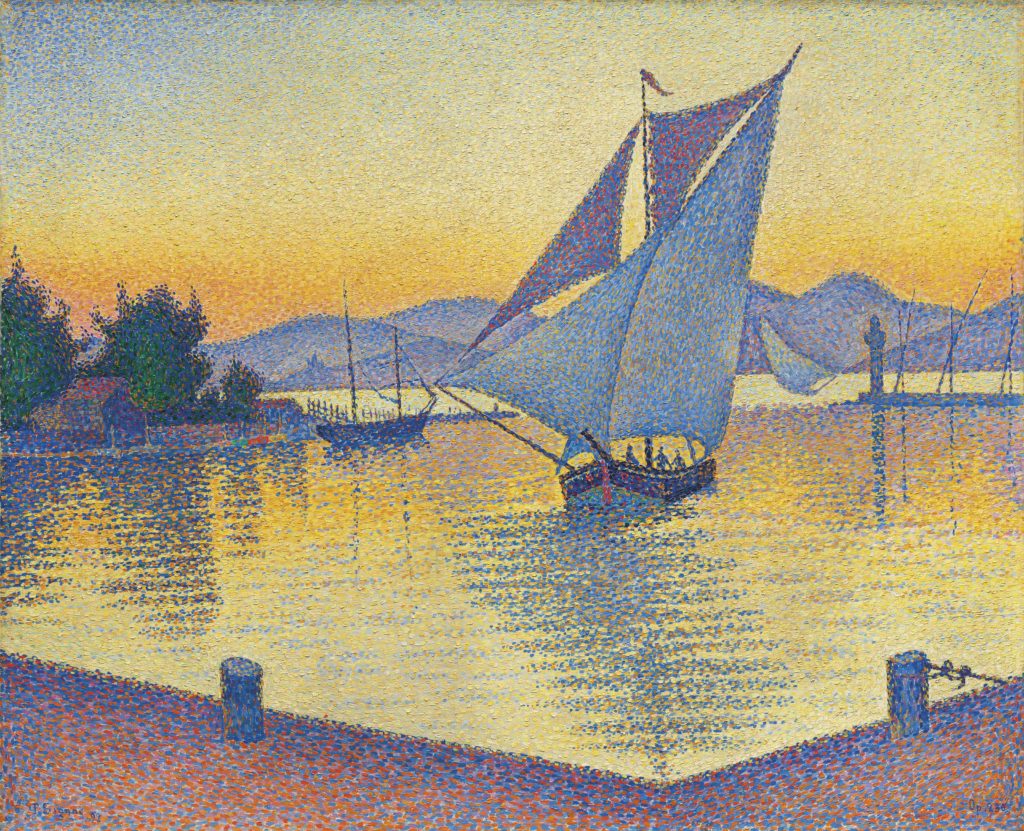

In this evening’s sale there were six paintings from his collection, with a collective £23 million low estimate, most of which were guaranteed. These were led by a luminous Pointillist seascape by Paul Signac, which last sold at auction in 1993 for $1.8 million to Acquavella, who then sold it on to Graham. Now estimated in record territory at £12 million, it achieved that and more, selling to the same unidentified buyer of the Renoir for £19.5 million ($25.8 million).

Gustave Caillebotte’s Chemin montant, 1881, sold for a world-record $22,079,469. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

Another top Graham lot was Caillebotte’s sun-dappled Chemin Montant (1881), which sold above estimate to an unidentified woman sitting with our unidentified Renoir buyer for a record £16.7 million ($22 million). Altogether, the Graham paintings fetched £44.5 million, which is more in line with how Christie’s wanted the evening to go.

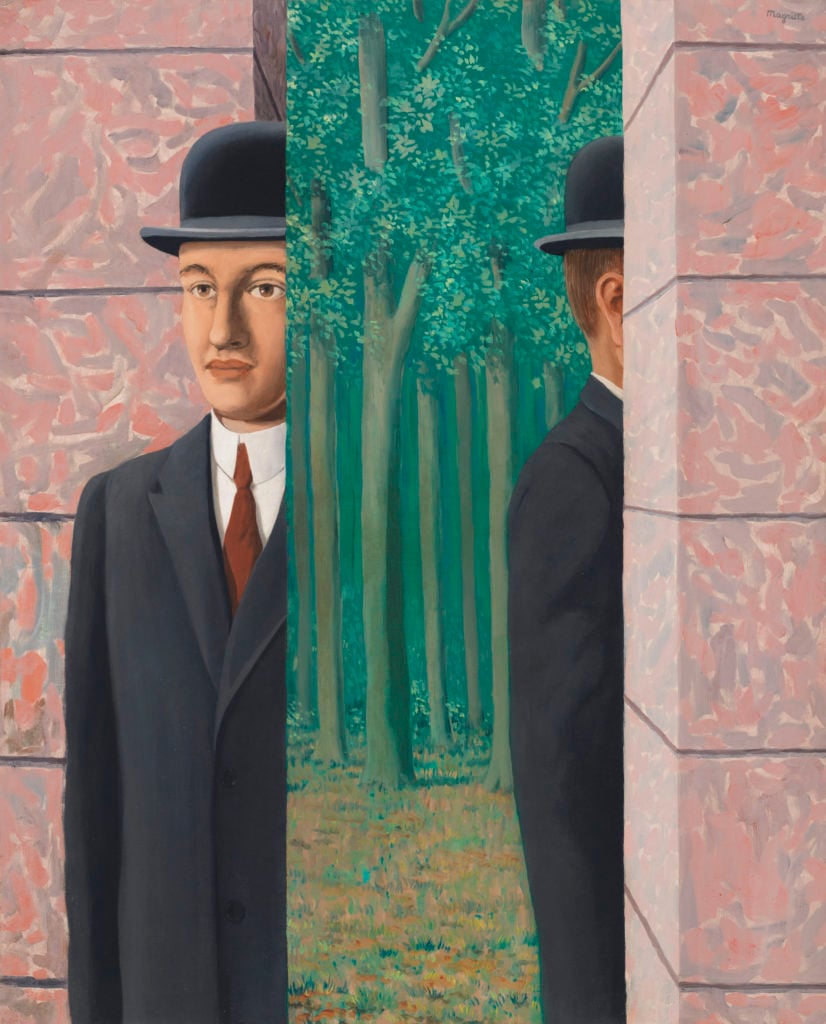

They are also sure to be pretty happy with the 34 Surrealist works in a separate catalogue, estimated at £32.3 million to £41.5 million, which realized £43.8 million ($58.3 million). This was arguably the strongest section, with only two lots not selling. The standout lot was Magritte’s mirrored bowler-hat painting, Le lieu commun (1964), which had an unofficial estimate of £15 million to £25 million, anticipating a new record for the artist. This was missed by a hair, selling to a phone bidder for £18.4 million ($24.3 million).

René Magritte, Le lieu common (1964) sold for $24,335,281. Courtesy of Christie’s.

In sum, apart from the overestimated Wallace collection, it was a solid performance for the market. Although Asian bidders were active, bidding on the top lots by Cézanne and Signac, and buying a mediocre Fauve river scene by Vlaminck on the low estimate for £4.7 million ($6.3 million), they did not make an outsize impression, and were visible bidding only on a few lots. Instead, Christie’s said, the evening’s bidders came from 25 different countries—enough of a spread to maintain London’s international trading status in spite of all its Brexit wobbles.