As a most unorthodox auction season continues apace, Christie’s raked in £90.3 million ($118 million) Thursday evening over the course of four sales in two different continents, all connected by video chat. The quadruple feature, “20th Century: London to Paris,” saw collectors and dealers watching from around the world as socially distanced specialists took phone bids on rostrums protected by virus-stopping dividers.

The novel arrangement did not electrify buyers, however. The hammer price across all the sales was £77.9 million ($101.9 million), barely over the low estimate of £76 million ($99.4 million). (Final prices include the buyer’s premium; presale estimates and hammer prices do not.)

More than half a year into lockdown, we are far from seeing light at the end of the tunnel. Salesrooms thrumming with the buzz of a bid-for-bid dogfight in the packed rows of seats—that’s a thing of the past. Instead, the houses try to drum up excitement through globe-spanning extravaganzas that might remind bidders of that bygone jet-set lifestyle they enjoyed just a year ago. Cécile Verdier, the auctioneer and Christie’s France president who was leading the proceedings in the City of Light, would often kick the bidding over to Jussi Pylkkänen in London, the gallic and anglo accents bounding off each other. (Another nice touch: the music drops that preceded bidding on a major lot, which sounded to my ears like a mix between the Daily Double siren and a trombone sample on a RZA cut.)

The salesroom at Christie’s London. Photo © Christie’s Images Ltd 2020.

But there was little spark in the sales themselves. The first, “Paris Avant-Garde,” slogged on as willing buyers failed to materialize, eventually grossing a hammer price of £15.52 million ($20.3 million), almost exactly at the £15.54 million low estimate, or £17.1 million ($22.4 million) with fees.

A work by Pierre Soulages—the 101-year-old living legend who may have even been watching the proceedings from his home in the south of France—sold to its guarantor for £4.5 million ($5.9 million) hammer, well below the low estimate. Several lots found no buyers, such as Daniel Buren’s Peinture acrylique blanche sur tissu rayé blanc et rouge, which had never come to auction—no voice on the other end of a phone was willing to breach the reserve.

Pierre Soulages’s Peinture 162 x 130 cm, 9 juillet 1961. Photo © Christie’s Images Ltd 2020.

The postwar sale came next, netting a sleepy if respectable £41.3 million ($54 million) hammer, just over the £40.9 million ($53.5 million) low estimate. With fees, the total was £49.2 million ($64.3 million).

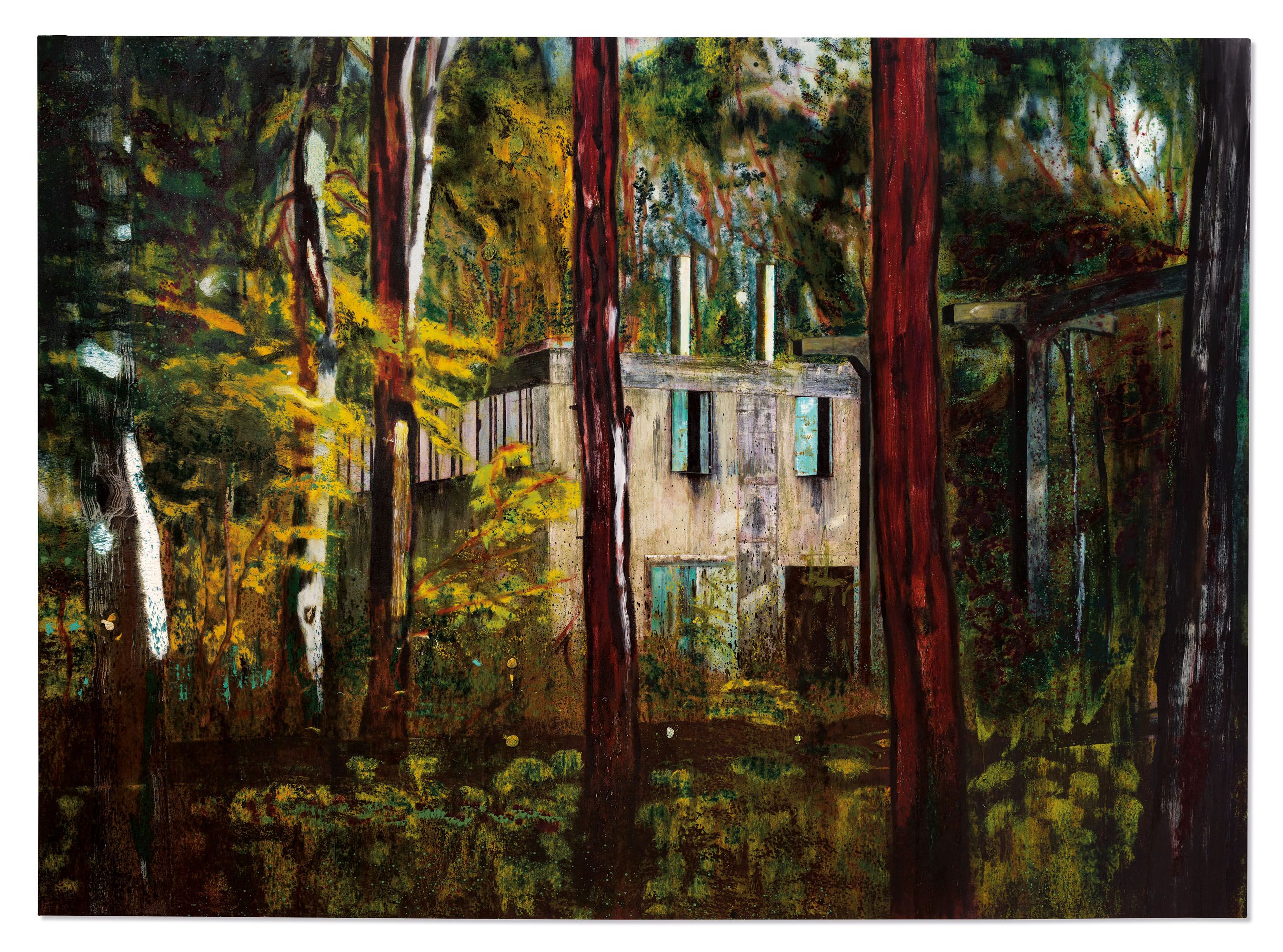

The top lot was Peter Doig’s Boiler Room, which sold to specialist Katherine Arnold for a £11.9 million ($15.6 million) hammer, short of the £13 million estimate. (With fees, it reached £13.9 million.) David Hockney’s Portrait of Sir David Webster, sold by the Royal Opera House to benefit future programming amid the prolonged lockdown, was expected to bring as much as £18 million ($23.6 million), but went to the guarantor for £11 million ($14.4 million), also on the phone with Arnold. (With fees, the price was £12.9 million.)

After those lots, Pylkkanen announced glumly that he would be skipping lot 112—Francis Bacon’s Head of Man, expected to sell for between £4 million and £6 million, had been withdrawn. An Albert Oehlen a few lots later, set to sell for between £2.5 million and £3.5 million, was also withdrawn—a sign of sparse interest in the run-up to the sale.

David Hockney’s Portrait Of Sir David Webster sold to raise vital funds for London’s Royal Opera House, which achieved £12.9 million. Photo: Christie’s Images Ltd 2000.

The event did contain some highlights—or, at the very least, solidify some of the trends bubbling up these past few weird months. There were strong results for artists including Titus Kaphar, Eddie Martinez, and Steven Shearer. The former two saw their stars rise as they got taken up by bigger galleries this year (Gagosian for Kaphar, Blum & Poe for Martinez), while the latter performed spectacularly in an experimental setting (Shearer’s Synthist sold for $437,000 as the first work on Christie’s alumnus Loïc Gouzer’s Fair Warning auction app). There was also a somewhat unexpected amount of bidding on a Per Kirkeby, which hammered at more than £100,000 over the high estimate.

While there wasn’t a T-Rex like at the Christie’s sale in New York, the house at least attempted to stage a record-setting gimmick of its own by making Marina Abramovic’s The Life the first mixed-reality work to ever be sold at auction. The editioned mixed-reality work, which comes in an edition of three and an artist’s proof, is 19 minutes long and allows the user to share space with a digital avatar of the artist as she paces around them. While it did secure the new auction record for Abramovic (whose performances and related ephemera don’t normally lend themselves to the auction format), buyers didn’t take to the work like they did to the Dino named Stan. The Life hammered at £230,000 ($300,856), short of the £400,000 low estimate, selling to the Brooklyn-based Faurschou Foundation.

The sale ended with a sputter as works by Günther Förg, Damien Hirst, and Franz West all sold for their low estimate or worse, and a Rudolf Stingel failed to find a buyer (the latest development in his dwindling market). The final lot of the evening, Anish Kapoor’s untitled wall sculpture, was estimated to sell for as much as £550,000—it was another pass.

Image courtesy of Marina Abramović and Tin Drum.

But that’s not all: the postwar auction was followed by “Thinking Italian Art & Design,” which brought in £5.9 million with fees ($7.7 million) over the course of the 18 lots that managed to sell—a severe disappointment, given that the low estimate (which does not include fees) came in at £9.7 million ($12.7 million). The sale’s sell through rate—54 percent—was equally dismal.

Also tallied as part of the evening (cannily designed to build out a hefty overall total) was a more successful special sale dedicated to the dealer Paul Haim’s collection of monumental sculptures. That mini-sale exceeded the £15.2 million ($19.9 million) estimate even without fees, fetching £16.8 million hammer ($22 million) and £18.6 million with premium ($24.3 million).

After the commercial marathon was complete, the house held a press conference simultaneously in London and Paris and tried to project a rosy tone, noting that the sales ably combined genre and era to reel in online bidders from around the globe. More than anything else, the ability to upend long-held ideas of the rigid auction-world calendar could work in their favor.

“It has relieved Christie’s of the tyranny of the calendar,” Christie’s CEO Guillaume Cerutti said. “We can choose the date that we want to sell based on our clients’ desires.”

Pylkkänen added that more than 200,000 people were watching the proceedings on various platforms—indicating that, even if “the vocabulary of the art market is changing dramatically,” there are upsides to a digitization of a previously very in-person world.

But the evening concluded with a reminder that the world outside the auction house remains very much in disarray. By the time the conference was over, at least one viewer was sympathizing with the staffers in Paris—many risked punishment as they left headquarters well past the 9:00 p.m. curfew set by French authorities.