During the crisp evening of the Cosmoscow collectors’ preview on September 16, a long line of people queued outside the Manege’s Roman columns. A stone’s throw from the Kremlin, the Manege became the surprise new location for the fair a week before it was due to open, when the government announced it would extend its use of the originally planned, more spacious Gostiny Dvor venue as a vaccine center. After an eight-day postponement of the fair, only three galleries pulled out, and Cosmoscow still boasted its largest number of participants yet at 77, including a number of first-timers, notably Hong Kong’s Pearl Lam Galleries.

Inside, a modular rearrangement was apparent, with blue shipping crates for walls and several gallery booths divided across two floors. Techno music blared downstairs, where the performance artist Dagnini, dressed as a schoolboy, spun around a carousel while peeing on a sandbox. The sculptures around her referenced ZHEK-art, or assemblages made of scrap material, tires, and beer bottles, a cultural phenomenon in post-Soviet courtyards. Nearby, artist and filmmaker Evgeny Granilshchikov, presented by LH Art Consultancy, performed selections from his Untitled (Maps) series, blindly drawing the borders of the Russian Federation in a sleeping mask. Art is never far from political commentary here. “Understanding the complexity of art practice in Russia is like uncovering layers of a matroyshka doll,” quipped Aleksei Afanasiev, an independent cultural advisor from Moscow.

Szena gallery’s booth at Cosmoscow.

The specificity of the local market is one reason Cosmoscow—now in its ninth edition—has at times struggled to gain its footing, with the region’s famously deep-pocketed collectors preferring to buy abroad and a historically thin collecting base at home. Founder Margarita Pushkina recalls how the fair debuted in 2010 with just 28 galleries—then promptly lost its venue to a developer. The organizers took some time to regroup and relaunched in 2014. “Local audiences were quite skeptical,” she said. “However, all the international professionals told us not to pay attention to negative opinions, and instead start building our own market, patiently and confidently. Nothing emerges by itself if we sit and wait.” To this end, last year Cosmoscow added a satellite fair for emerging art, Blazar, which proceeded at the Museum of Moscow during the fair’s original dates.

Despite a lack of Western collectors due to Covid-related travel concerns and restrictions this year, Pushkina’s patience in growing the local market may be paying off. “There is an expat community and they are buying actively,” she said. “We can see there’s a trend towards creating more thoughtful collections. Collectors’ appetite for more “complex” art is growing.” Young entrepreneurs and IT professionals are bypassing traditional media for installations and objects, “making more daring choices,” she added.

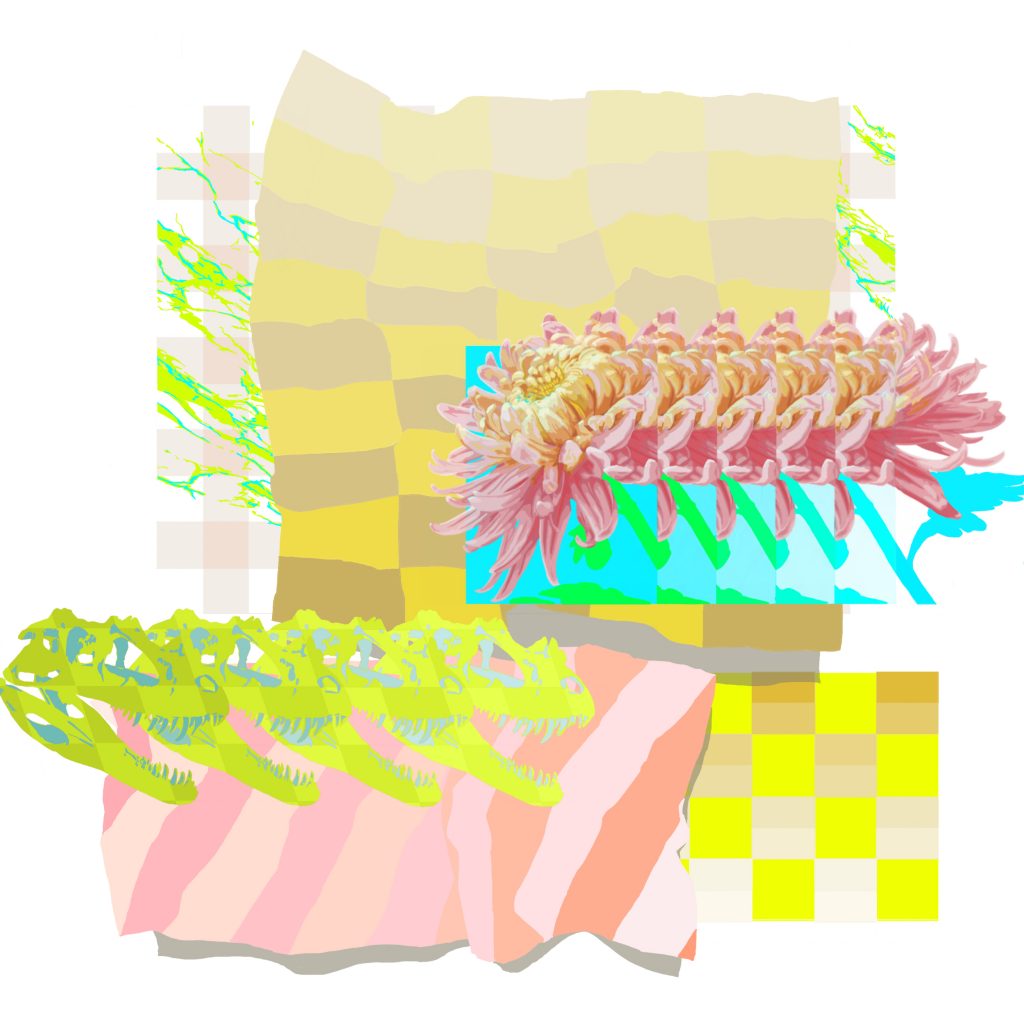

Alexander Zabolotny, Still Life with Chrysanthemum. Shown at Cosmoscow by Art & Brut gallery, Moscow.

At the Manege, dealers hoped to capitalize on the youthful energy generated by Blazar the week prior. Antwerp-based Nadya Kotova, who was showing mid-career artists such as Taisia Korotkova and Kirill Chelushkin at prices between €6,500 and €17,000, said that although her existing clients in Moscow fit the stereotype of male business owners, she is seeing a shift. “I’ve come across a few buyers who have just started collecting,” she said. Nikolay Palazchenko, who heads Art Basel’s VIP relations for the region, affirmed that different collectors are coming into the fold, citing Ksenia Chilingarova, Denis Khimilyane, and Aleksei and Vera Priyma, whose Social Realism and avant-garde works were featured in the fair’s Collector’s Eye section this year.

Russian nonconformism in art history was matched with post-internet art throughout the fair. Yekaterinburg-based Ural Vision—which will soon open a new branch in Vienna—was showing the 34-year-old Vladimir Abikh, whose lenticular prints of Instagram pages play with the instantaneity of the image (€2,500 each). Art & Brut, an eight-year-old collective of artists, designers, and architects, saw success with playful, glitchy paintings by Alexander Zabolotny, cracked ceramic works by Irina Razumovskaya, and abstract ruptured canvases by Kirill Basalaev, all between €1,800 and €4,700. It’s telling that the most expensive sale reported at the fair—€45,000—was by digital-art pioneer Olga Tobreluts, at Moscow’s Pogodina Gallery.

Artwin gallery’s booth at Cosmoscow, featuring Siberian artifacts and Soviet toys by Evgeny Antufyev and Lyubov Nalogina.

Vienna gallery Zeller Van Almsick’s stunning presentation of minimalist Jonny Niesche’s vibrating, chromatic works sold seven works for €10,000 each, to both Russian and international collectors. Art Agency Sofia’s dramatic booth was also well received: Austrian activist Iv Toshain’s aluminum Iron Curtain had a number of buyers vying for it at €30,000, and two of Tim Parchikov’s Burning News photographs—people clutching blazing newspapers in snowy landscapes, a reference to the Bolshevik Revolution—sold for €15,000 each to a Russian foundation.

Moscow- and NYC-based Fragment—one of two galleries at the fair continuing on to Art Basel this week—offered a tantalizing display with red velvet curtains and dark sexual fantasy paintings by Lisa Ivory, most of which found local buyers. Affordable limited editions were also popular, with the best example being Shaltai Editions, a gallery created by collector Valeria Rodnyanskaya, whose graphic language combines leading figures of Moscow Conceptualism, such as Viktor Pivovarov and Andrey Monastyrsky, with artists of the younger generations.

Art Agency Sofia’s booth at Cosmoscow, featuring works by Tim Parchikov and Iv Toshain.

Following the Chinese Conceptual artist Zhang Huan’s first solo exhibition at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg in late 2020, Alyona Ivanova, director of Pearl Lam Galleries in Russia, sold works by Zhang and Mr. Doodle to Asian collectors before the fair’s opening, thanks to TEO, the online marketplace for contemporary art in Russia (TEO will continue to host fair sales until September 26). “I’m curious to see if Russian collectors are ready for this kind of art,” she commented.

All told, Cosmoscow welcomed a sizable crowd of 15,000. Collectors’ tastes may be changing, but it’s also a new era, observed Teresa Iarocci Mavica, the director and cofounder, with Novatek billionaire Leonid Mikhelson, of the V-A-C Foundation in Venice. In Moscow, they are about to open the Renzo Piano-designed GES-2 House of Culture in a disused power station. Outside the structure, Urs Fischer’s amorphous Big Clay #4 has been installed alongside Vodootvodny Canal, looming distantly opposite the eyesore monument to Peter the Great. “Twelve years ago, when we were developing the foundation, we were in a different situation,” she said. “If you want to build a language for the future, you have to look at the artists who are working now.”