Nothing gold can stay, and every art-industry veteran understands that the good times don’t last forever.

Beneath the big-money rumblings of last November’s New York auctions—a bellwether slate of sales unfolding just a few weeks after the 10-year anniversary of the Great Recession dredged up memories of titanic losses—it wasn’t hard to hear a consistent, if sotto voce, stream of concern about a looming market downturn. The chatter only grew louder after several of the week’s marquee lots were greeted by lackluster demand or failed to find buyers entirely, dimming sentiment on the decent yet somewhat uninspiring overall results—and perhaps on the market’s prospects as a whole in 2019.

A few months later, against the backdrop of Brexit and other political uncertainties, many in the trade remain wary about the near future. Another decline is inevitable. When it will begin, and how harmful it will be, remain open questions. Rather than speculate about those impossible-to-predict answers, however, we’ve set out to examine past market contractions for lessons that could prepare us for the next one. Because no matter how unappetizing it may be to sell art in a downturn, someone is going to have to do it.

To this end, we combed through fine-art auction data from 2005 through 2018, with a special focus on the crisis in 2008–9 and the more recent art-market hiccup in 2016. (These were the only downturns for which our analysts felt sector-wide data could be considered complete and reliable.) After contextualizing the results with firsthand experience from market experts who were in the trenches during these tumultuous chapters, we teased out three pieces of advice to potential sellers in the next recession.

Total Fine Art Sales at Auction 2005-2018. © 2019 artnet Intelligence Report.

1. Don’t be afraid to sell a masterpiece, because great works can still fetch great prices in downturns.

Since the financial crisis didn’t make landfall until September 2008, global fine art sales at auction only dropped about 12 percent that year, to roughly $10 billion. It was 2009 that bore the brunt of the impact, with total sales plummeting to just $6.4 billion—the lowest annual total in our sample other than 2005, when the market was smaller but still on an upward trajectory.

Despite the drop, the market nonetheless produced some extraordinary results during this year-long hurricane. The art dealer Daniella Luxembourg, who formerly served as president and co-owner of the Phillips, De Pury & Luxembourg auction house, highlights Christie’s historic sale of works from the collection of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé in February 2009. The collection included objects ranging from Old Master paintings and Constantin Brancusi sculptures to Qing dynasty bronzes and 18th-century Italian dining chairs. It racked up $484 million in sales and set six artist records en route to becoming the most valuable private collection sold at the time.

Christie’s auction of a painting by Dutch artist Frans Hals, Portrait of a man holding a book, on February 24, 2009 at the Grand Palais in Paris. Photo: PIERRE VERDY/AFP/Getty Images.

Together, Christie’s and Sotheby’s sold a combined total of about $4.5 billion in fine and decorative art at auction in 2009. This means the Saint Laurent collection alone accounted for roughly 11 percent of the Big Two’s sales that turbulent year—a staggering proportion that speaks to the enduring value of masterworks. As Luxembourg explains, “It doesn’t always affect all the works of art” if the market enters an extreme low (or high). “It just affects the fashionable, of-that-moment works of art.”

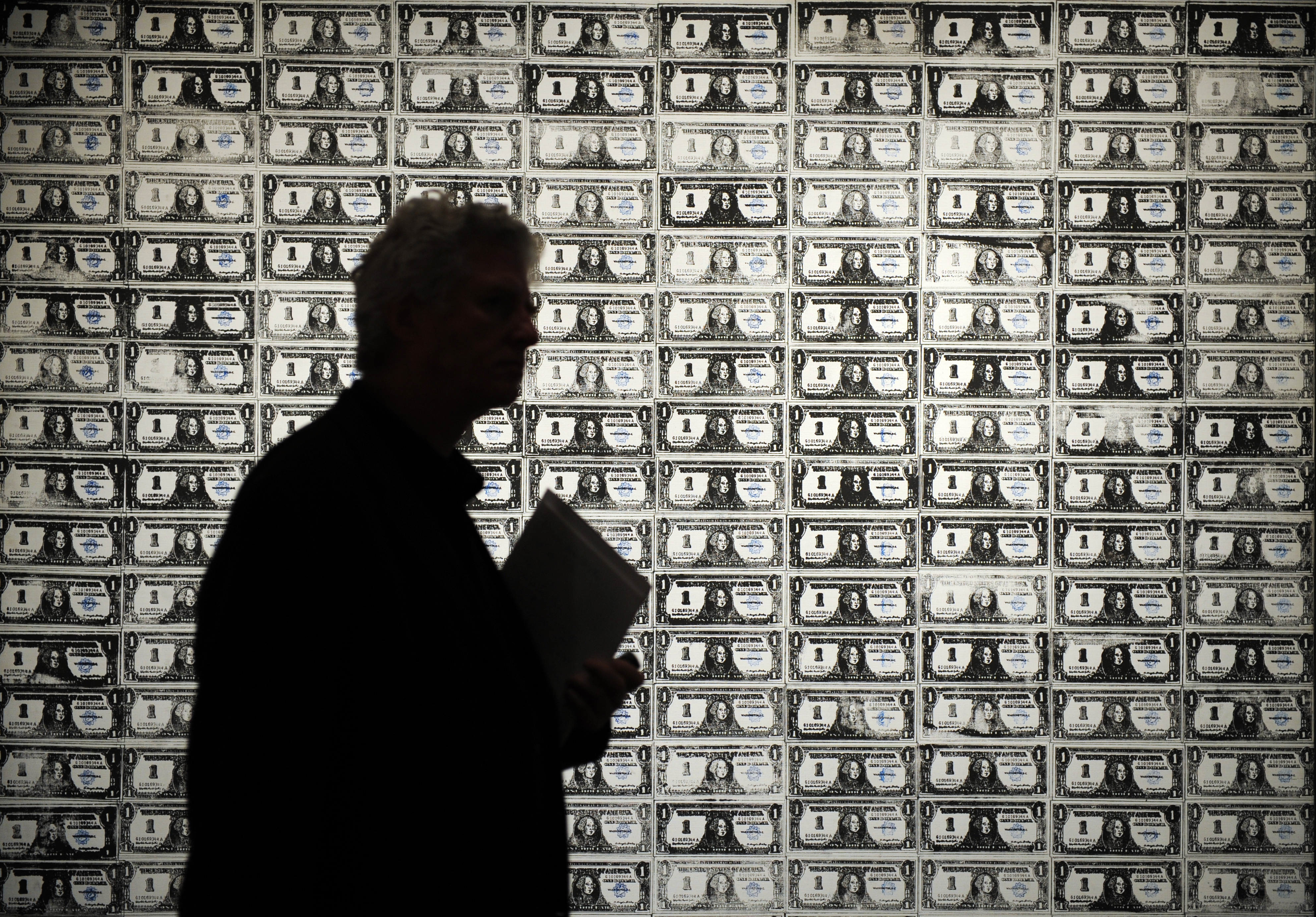

This maxim proved true again in November 2009, when Andy Warhol’s 200 One Dollar Bills vaulted more than three-and-a-half times over its $12 million high estimate to sell for $43.8 million at Sotheby’s New York. One of only 10 Warhol canvases featuring more than two greenbacks, the work was previously owned by early mega-collector Robert Scull and returned to market for the first time in 23 years. “For [200 One Dollar Bills] to sell for over $40 million in the middle of the most morose market ever signaled that the market is still pretty much there,” says legendary auctioneer Simon de Pury, who credits the exuberant sale with helping to pull the trade out of its funk.

But did the market ever really leave? Or were there just few sellers offering works of rare quality? “What dries up in down markets is discretionary consignments,” notes de Pury. Data bears this out for blue-chip works. In 2009, the number of pieces consigned worldwide with a low estimate between $1 million and $10 million dropped almost 60 percent, to just 443; and the number of works consigned with a low estimate of $10 million or higher dropped nearly 75 percent, to just 12. (Broadly similar but less severe declines occurred in the 2016 downturn.)

© 2019 artnet Intelligence Report.

So it’s possible that more sellers could have snagged healthy returns sooner if they’d applied Warren Buffett’s classic adage about investing: Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.

2. If you need liquidity in a contraction, your best bet is to sell a work estimated between $100,000 and $1 million.

On average, works traded for between $100,000 to just under $1 million showed the smallest overall percentage drop in 2009 and 2016, two years in which total fine art sales at auction declined more than 20 percent from the previous year. The average sales price within this band dipped only about 1.5 percent in 2009, then actually gained 0.3 percent in 2016, outshining the year-over-year performance of all other price bands in our sample.

© 2019 artnet Intelligence Report.

De Pury reminds us of the sound economic logic beneath this phenomenon. He describes the art market’s socioeconomic structure as a pyramid, with only a handful of collectors able to pay $100 million or more for an artwork even in a heady year. The population of willing and able buyers multiplies when you descend to the $10 million price range, but remains thin. “At $1 million,” however, “a pretty large group can buy.”

Incidentally, Suzanne Gyorgy, Citi Private Bank’s global head of art advisory and finance, notes that her clients’ general “sweet spot” has been edging ever higher over the past two years, settling between $500,000 and $3 million. However, she primarily attributes the recent uptick to the quality of works available at auction in a relatively healthy 2017 and 2018, particularly due to extraordinary estate sales like Rockefeller. (Estates stand as arguably the best—and sometimes, the only—way for auction houses to secure great works in troubled times. Death and estate taxes don’t care about bad timing.)

Given what we know about the scarcity of great works consigned during contractions, then, it seems prudent for sellers to hew to the more conservative price band between $100,000 and $1 million during the next downturn.

3. Consign to the art market experiencing the least turbulence, because even in a global downturn, different regions perform differently.

Comparing the past decade of auction sales in the US, UK, and China, the art market’s three dominant regions, one feature stands out: A strong (or weak) year for one is not necessarily a strong (or weak) year for all.

The scale of divergence was most extreme in 2009. Total sales of fine art at auction that year plummeted by more than half in the US and nearly two-thirds in the UK—but more than doubled in China, from about $711 million to over $1.44 billion. (All regional figures for China combine the mainland and Hong Kong.)

© 2019 artnet Intelligence Report.

What accounts for the gargantuan discrepancy? Benjamin Mandel, global strategist for multi-asset solutions at JP Morgan, highlights China’s long-term trend for more robust economic growth (thanks to its status as an emerging market) and a two-year, $585 billion stimulus package announced by the state in November 2008. The latter ushered in softer monetary and fiscal policies, largely to accelerate provincial and local infrastructure projects. The effect likely bolstered sentiment in the country’s art market as well.

China’s outsize ascent didn’t last forever. By 2015—notably, a year in which China’s fine art sales crashed (along with its stock market) while the US’s surged—”you’re already seeing a stabilization of metrics for what China’s long-run size might look like,” explains Mandel. “But back in 2008, you were still very much in an extraordinary growth period for art-related sales. When you add that as an additional layer to the underlying macroeconomic story, you have a pretty good explanation for why the Chinese art market continued apace” in 2008, even as the financial crisis temporarily dragged the American and British art markets under the waves.

When selling in a downturn, then, choosing the right sales venue in the newly global art market looks just as important as offering works of extraordinary quality or appealing value. Strategizing wisely, let alone having the courage to pull the trigger, may not be easy. But the good news is that, no matter how bleak things may appear overall, opportunities still exist. Daniella Luxembourg said it best when she said: “Art was always expensive, and [yet], somehow, there is always money for art.”

This story first appeared in the artnet Intelligence Report. For an in-depth breakdown of the global art market’s performance in 2018, a buyer’s guide to the Venice Biennale, and more must-read art market analysis, download the report here.