Art & Exhibitions

‘Crow’s Eye View’ at Tina Kim Gallery Delves Into Korea’s Tumultuous History

The show offers a view through the lens of architecture.

The show offers a view through the lens of architecture.

Eileen Kinsella

Undoubtedly one of the most ambitious and educational shows of the fall season is “Crow’s Eye View: The Korean Peninsula,” which opened September 10 at Tina Kim Gallery in Chelsea. The show is the brainchild of South Korean architect Minsuk Cho, commissioner of the Korean pavilion at the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale this past year, and co-curators Hyungmin Pai, a professor in the architecture department at the University of Seoul, and Changmo Ahn, a professor at Kyonggi University.

Borders, Crow’s Eye View: The Korean Peninsula; Tina Kim Gallery, NY, 2015. Photo by Jeremy Haik

Originally conceived for and exhibited at the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale held last year (June 7–November 23), where it won the Golden Lion prize, and later shown in Seoul at the Arko Arts Center, the show delves into the past 100 years of Korea’s history, homing in on the post-WWII split into North Korea and South Korea that effectively created two countries that have “radically divergent yet irrevocably interconnected economic, political, and ideological systems,” according to Cho.

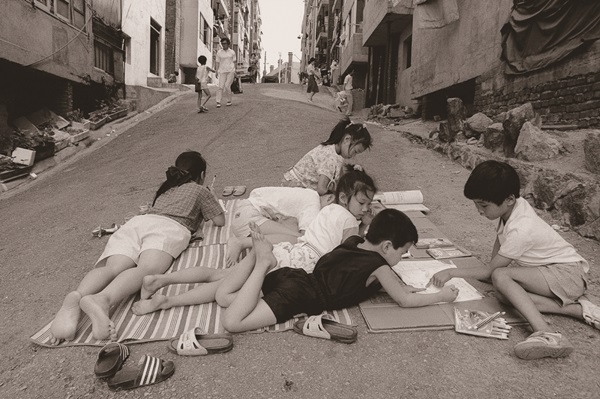

Kichan Kim, Seoul Ahyeon-dong, 1989 © Kichan Kim

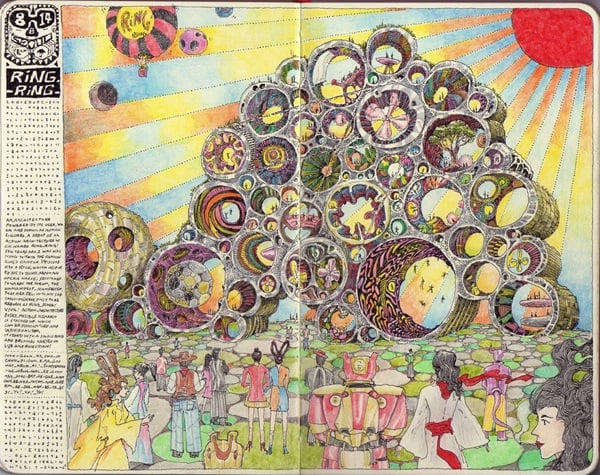

Though the respective architectural evolution of each country is obviously a major focus, the show is also packed with material—historic photographs, books, travel posters, architectural models, futuristic drawings, contemporary paintings, and installations, from a wide range of artists, including photographers, visual artists, documentary filmmakers, and writers.

Prologue/Atlas, Crow’s Eye View: The Korean Peninsula; Tina Kim Gallery, NY, 2015. Photo by Jeremy Haik

artnet News sat down with Cho and Pai at Tina Kim’s newest space on West 21st street a few days before the show opening to discuss how it took shape.

It seems there is no aspect of this exhibition that is not already a story embedded in another story, starting with the inspiration for the show. Cho, who is principal of Seoul-based architectural firm Mass Studies, was inspired by Biennale curator Rem Koolhaas’s chosen theme, “Absorbing Modernity 1914–2014.”

Reconstruction Life, Crow’s Eye View: The Korean Peninsula; Tina Kim Gallery, NY, 2015. Photo by Jeremy Haik

“If it was just the last 50 years it would be a completely different show,” Cho explained, “because then you can just deal with South Korea. Because it was 100 years, it dated back to when Korea was a colonial state of Japan,” after it was annexed in 1910. “If you have to pinpoint one situation or condition of Korean modern history, it would have to be the division of the North and South” that happened in the immediate aftermath of World War II.

Ahn Sekwon, Cheonggye Stream’s View of Seoul Lights (2004) © Ahn Sekwon

Both Cho and Pai said they felt this presented a unique opportunity noting how many previous attempts to explore this concept have been “sensationalized or over-simplified,” which they say only further reinforces clichés and prejudices.

Since South Korean citizens are not permitted to visit or communicate directly with North Korea, Cho had to rely on a seemingly random group of outside mediators—an Austrian curator in Vienna, Peter Noever, who curated a 2010 show about North Korea, a Beijing-based British man named Nick Bonner who founded a tour company specializing in trips to North Korea, and a French photographer who photographed North Korea in the late 1950s—both to attempt communication with North Korean officials and gather information and materials about the country.

“South Koreans are probably the only country that cannot go to North Korea,” explained Cho. “Even if we have to contact North Korea, a third person—a non Korean European or American will have to be involved. So from the beginning, it was a political process.”

Moon Hoon, Ring-Ring (2011) © Moon Hoon

Cho says that while there was never a firm “no” from North Korean officials, he and his team never got a firm answer either. So the show is admittedly from the South Korean perspective.

“I begin by stating the obvious,” Pai wrote in an essay for the Biennale catalogue. “I know very little of North Korean architecture. I shall also declare that this has not disqualified me from being a curator for an architectural exhibition of North and South Korea.”

The show is arranged around several themes rather than chronologically, and it serves the exhibition well. These include “Reconstructing Life,” “Monumental State,” Utopian Tours,” and “Borders” which examines the demilitarized zone or DMZ from fascinating perspectives.

The title of the show was taken from a serial poem of the same name by an early 20th-century Korean architect-turned-poet named Yi Sang (1910–1934) who was heavily influenced by the Dada movement. Cho described the poem as the “emblem of the fragmented vision of a Korean poet who aspired to be a modern architect, an aspiration that was impossible to fulfill under the debilitations of Japanese colonial rule.”

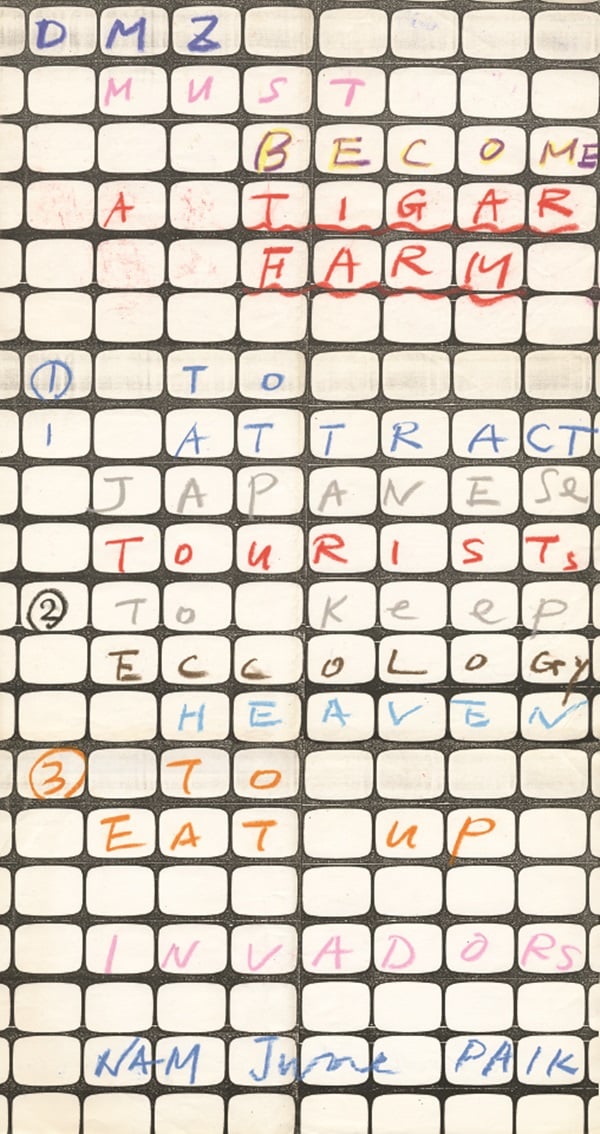

Nam June Paik, Untitled (ca. 1988), from Project DMZ,

Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York Courtesy of the Storefront for Art and Architecture Archive

Another fascinating bit of history that Cho uncovered during his research was artist Nam June Paik’s involvement in helping Korea get a pavilion in the Giardini. It was the last remaining available pavilion in the Giardini in 1995 when it was designated. Attempting to capitalize on a rare moment of relative calm between the two countries, Paik proposed that it be a pavilion for both North Korea and South Korea. Though he made some progress, as Cho retells it, the plan failed to come to fruition, largely because of the death of North Korean leader Kim Sung-Il in 1994.

Girl running through Kim Il-sung Square; photo by Chris Marker. Koreans, Untitled #16 (1957).Courtesy of Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Today, the pavilion, which has only ever been used for South Korean projects for both the art and architecture biennales, simply bears the name Korea, and not the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) or Republic of Korea.

The show continues through October 17.

Related Coverage:

New US Pavilion at the Architecture Biennale Targets Detroit