A new sculpture by Robert Indiana has just shown up at the Milwaukee Art Museum—well, new and not new.

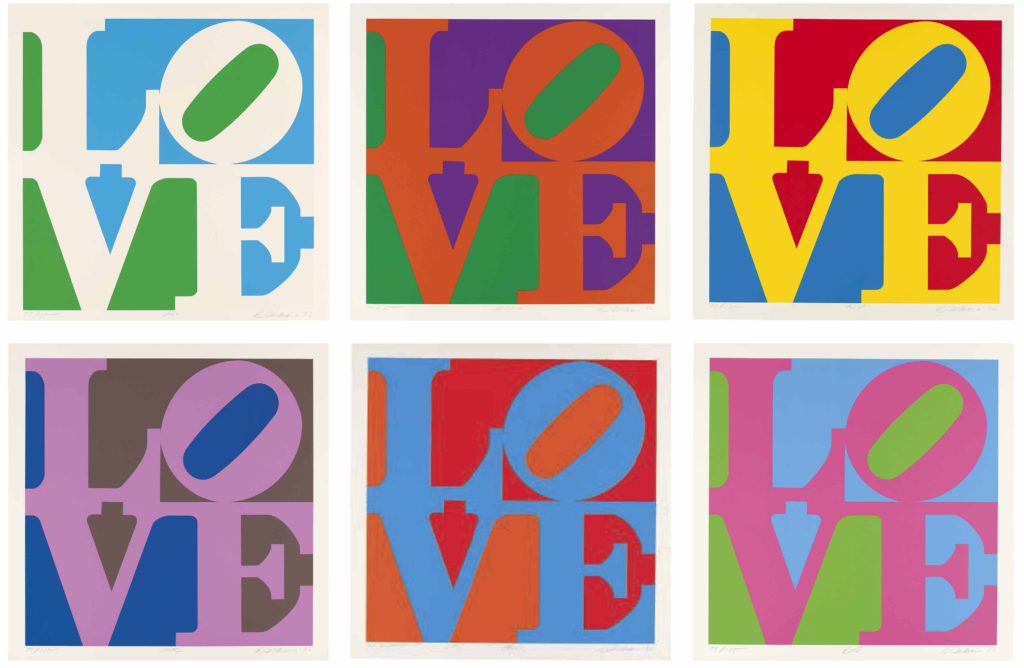

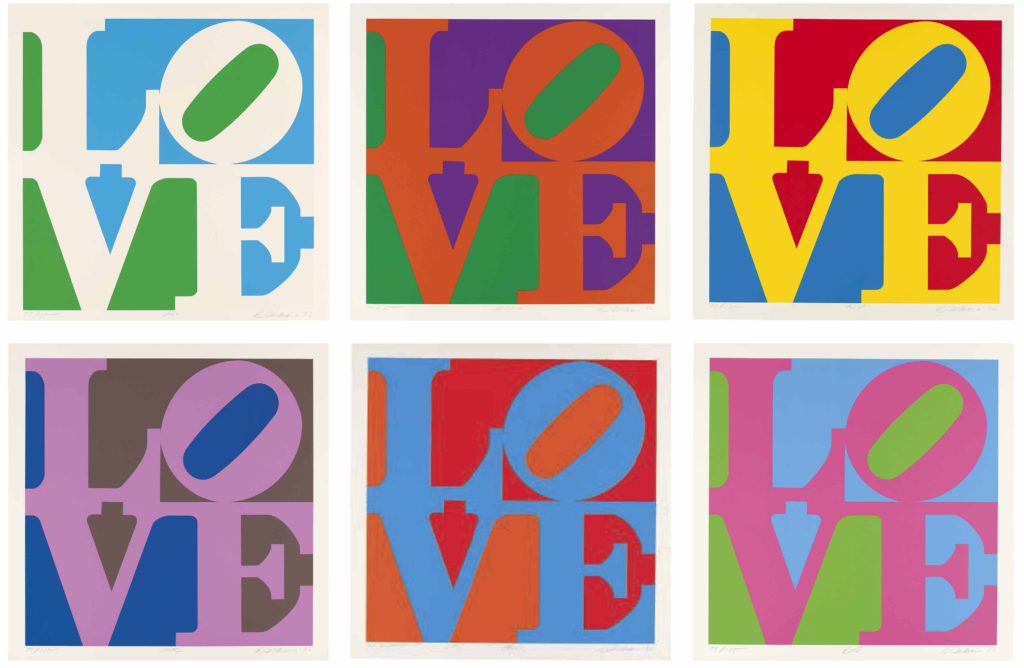

The work is an edition of the ubiquitous LOVE image that dates back to the mid-1960s, when it was first printed on a Museum of Modern Art Christmas card. The Milwaukee work, which was donated to the museum by an anonymous donor through the Greater Milwaukee Foundation, will be unveiled on September 5, and its dating is a bit funny: 1966–99. Will visitors to the museum assume that the artist, who died last year, worked on the sculpture for 33 years?

Most museums with contemporary and modern art have objects with hyphenated or double dating, which curators sometimes make a point of explaining on didactic labels.

“A date range can mean a variety of things, from the artist literally working on the work consistently for the dates included in the range, to the artist coming back to work on it during the years included in the date range, to the case of the LOVE sculpture, where the artist acknowledges the date of the original design of the sculpture, along with the date of execution,” says Margaret Andera, the Milwaukee museum’s curator of contemporary art.

Indiana (1928–2018) began making LOVE sculptures in 1970, first in weathering steel and later in a variety of materials, and posthumous castings continue to be produced by his estate. In the case of the Milwaukee work, the final date in the range, 1999, refers to the year this particular piece was made.

Robert Indiana, Garden of LOVE (1980s). Courtesy of Christie’s.

Age Is Just a Number

The art trade’s dating system occasionally leaves onlookers scratching their heads.

For example, in 2011, the Manhattan-based Roy Lichtenstein Foundation authorized a casting of Coups de Pinceau, a 30-foot tall sculpture originally made in 1988, and called it a “posthumous artist proof” (the artist, who was born in 1923, died in 1997). In a separate instance, the Paul Kasmin Gallery in 2013 exhibited five polished bronze sculptures produced by the Constantin Brancusi (1875–1957) estate in 2010 from molds left after the artist’s death. The sculptures were dated 1992–2010 and made in editions of five or eight. Brancusi, of course, had nothing to do with the re-castings.

“Occasionally we have to explain that to people, especially at art fairs when you get 75,000 people coming into your booth over the course of three days,” says Eric Gleason, a director at the Kasmin Gallery.

While alive, the artist hand-polished each of his bronzes, and every one of them is uniquely finished. The differences between bronzes polished by Brancusi himself and those finished by someone else may be a bit subtle for most viewers, but art is based on subtleties.

“We strive for transparency and clarity,” Gleason says, adding that the price of the posthumous Brancusi bronzes—between $4 million and $10 million—are nowhere near that of the lifetime sculptures, “which start at $50 million to 60 million.”

Double and hyphenated dating also occurs with works by living artists. A forthcoming exhibition at the Kasmin Gallery by Bernar Venet (b. 1941) includes two works made 10 years ago that were reworked for this exhibit. According to gallery director Emma Bowen, one of those works—a 2010 piece titled Indeterminate Line—was “completely reworked by adding a second element.” The new configuration is now called Two Indeterminate Line and is dated 2010–19.

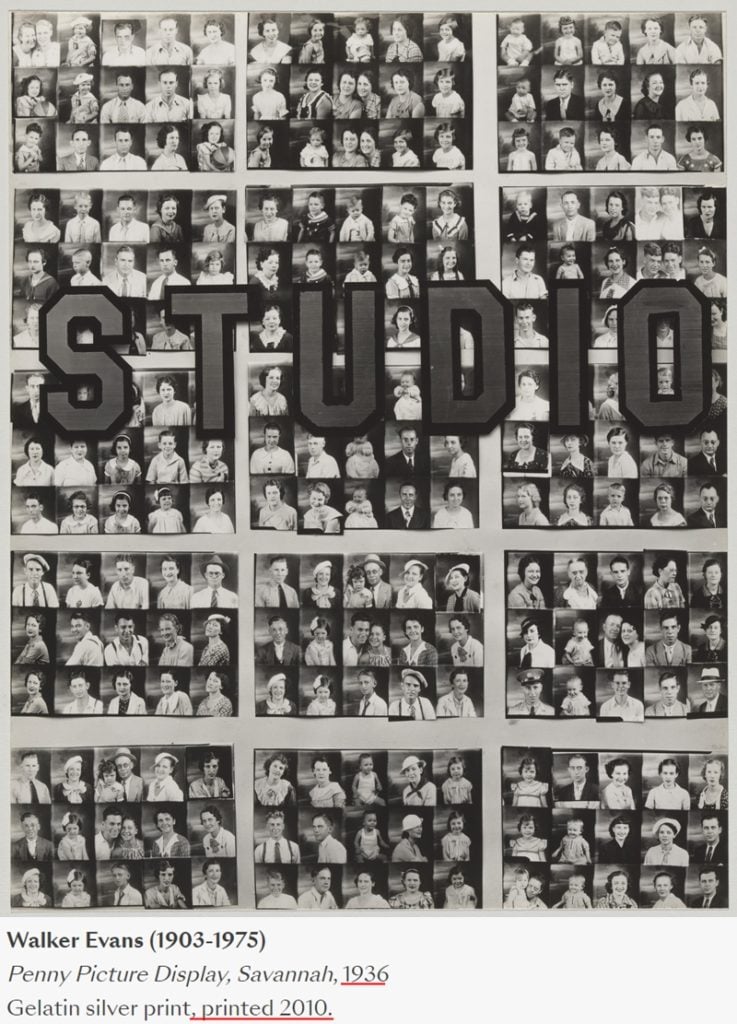

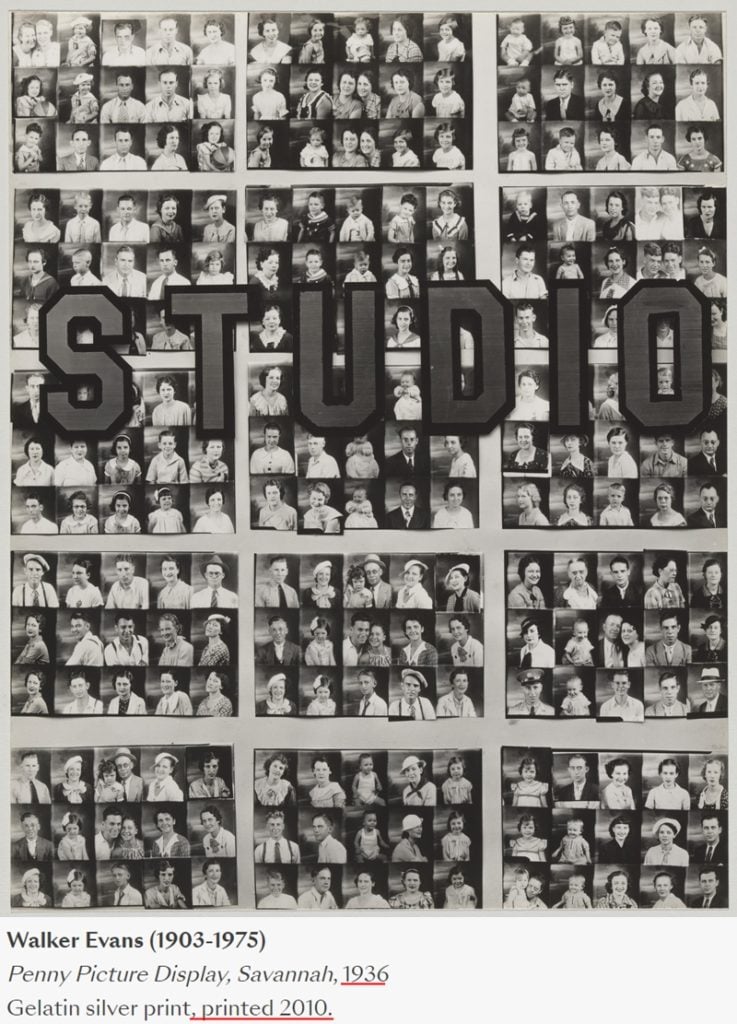

The catalogue entry for Walker Evans’s Penny Picture Display, Savannah for when it was for sale at Bonhams. Courtesy Bonhams.

What an Earlier Edition? You’ll Pay More

Double dating works has become increasingly common, especially in the photographic print market, where the gap between the year in which a picture was taken and the year in which it was printed can be decades wide.

For instance, in a Bonhams photography sale last April in New York, a Walker Evans (1903–1975) image titled Penny Picture Display, Savannah was dated 1936 but printed in 2010. It sold for $11,325 with buyer’s premium—a modest amount, but at least it sold.

Compare that to versions of the image from a Phillips London sale in 2016 (“probably printed 1960s,” estimated at $25,000–35,000) or one from Santa Monica Auctions (“printed early 1970,” estimated at $20,000–25,000), both of which were bought-in. (According to the artnet Price Database, editions of the photograph have been for sale at auction 24 times since 1989 and have been bought-in six times.) In 2003, Christie’s sold an actual 1936 print of the image for $197,900 with buyer’s premium, above its $100,000–150,000 estimate.

The April Bonhams photography sale in New York also included a “1970s” print of Ansel Adams’s (1902–1984) Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, a picture taken in 1941 that is one of perhaps 900 prints of the image produced by the artist over a 40-year period, according to his grandson, Matthew Adams.

The work sold for $32,575, which is in the mid-range for prints produced by the artist in the 1970s, says Emily Bierman, head of Sotheby’s photography department. The top auction price for a Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico work, printed in the late 1940s, is $609,600 with buyer’s premium, which was achieved at Sotheby’s New York in 2006.

“A premium is paid for the earliest examples because that gets you closest to the artist’s original intentions when the picture was taken,” Bierman says, adding that by the 1970s, Adams’s approach to the image had changed. More recent prints of the work have higher contrasts, with the clouds and moon looking much brighter. And even though the later versions have become the “iconic” image, the market still favors earlier examples.

In general, there is a traditional pricing hierarchy based on when a photographic image was printed, says Frish Brandt, president of San Francisco’s Fraenkel Gallery. Topping the list are prints that are “vintage”—that is, “contemporaneous with the negative”—followed by “a piece that is printed later; then a piece printed a lot later; and a piece that is printed posthumously.”

Collector Rick Norsigian showing prints from found negatives by Ansel Adams. Photo by Lawrence K. Ho/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

With Photographs, It Matters Who Made the Print

Whether the photographer printed the work personally also affects pricing, especially in America. “In the United States, who did the actual printing is very important, but it is not as important in Europe,” Brandt says, noting that Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004) regularly had other people print his images, which has not negatively impacted the market for his work.

Shlomi Rabi, head of photographs at Christie’s New York, notes that a lifetime print of Diane Arbus’s (1923–1971) Identical twins, Roselle, N.J., 1966 sold last October at Christie’s for $732,500 with buyer’s premium (just above its $500,000–700,000 estimate), making it the second-highest priced single work by the artist to trade hands at auction. (The highest price achieved for an Arbus work was $792,500 with buyer’s premium in 2018 at Christie’s New York for a portfolio of ten photographs.)

On the other hand, the same image printed after Arbus’s death by her long-time printing collaborator, Neil Selkirk, “is likely to fetch between $60,000 and $100,000 at auction,” Rabi says. A lifetime print, he argues, is more likely to achieve “the right tonality, texture, mood and print quality that the artist aimed to achieve. A posthumous print invariably removes that intimacy and that connection.”

The importance of a “vintage” print, Brandt says, is “more relevant to photographers of an earlier time. New collectors collecting new works don’t think about it at all.” Museum curators, however, still tend to esteem vintage works more than later prints, she said, but their institutions’ pocketbooks often make them more flexible in their outlook.

“Curators tell me, ‘We really, really want this picture for our collections.’ But their budgets determine if they buy a lifetime or posthumous work.”