Art & Exhibitions

At Moretti Fine Art, A ‘Donatello’ Keeps Us All Aflutter

THE DAILY PIC: A Renaissance sculpture refuses to let us get a bead on it.

THE DAILY PIC: A Renaissance sculpture refuses to let us get a bead on it.

Blake Gopnik

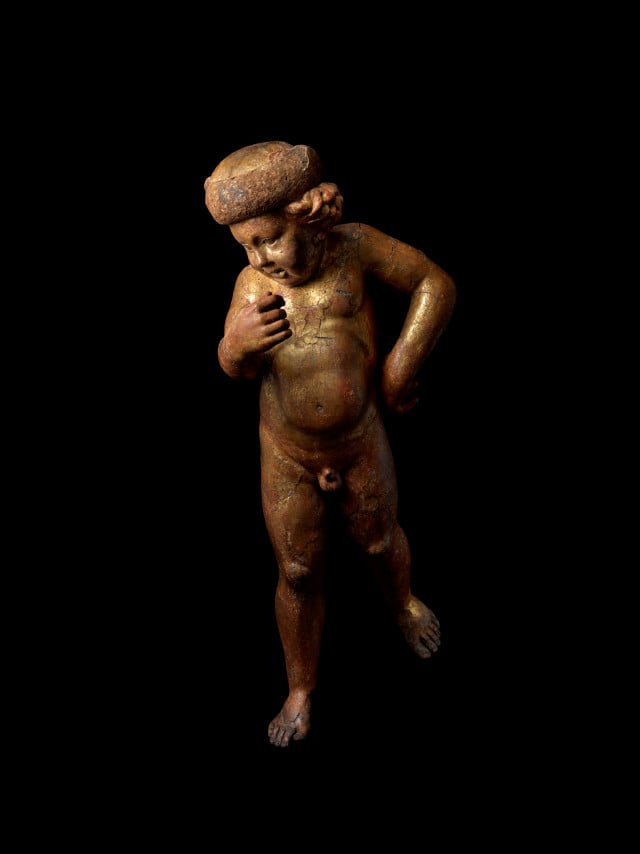

THE DAILY PIC (#1441): Today is the last chance to catch this carved wooden “spiritello”, newly attributed to the great Renaissance sculptor Donatello by the scholar Andrew Butterfield. It is on view for one final day at Moretti Fine Art in New York. Although the new attribution is what’s getting air play, I don’t much care if the thing is by Donatello or some rival or pupil or imitator of his in Florence in the 1430s. What I care about is the way the sculpture of this winged toddler messes with anyone who tries to get a grip on it.

Yesterday, I spent a solid hour looking at the piece with Butterfield and the art historian Alexander Nagel. Among other things, we tried to puzzle out how and where the thing might have been positioned when it was new, and what viewpoint it is meant to be seen from.

I became pretty convinced that it once was sited far overhead, since looking up at it from almost flat on the gallery floor shows it at its best: The creature’s gaze meets yours, and some of the oddities in its face and right arm disappear when seen from far below. Nagel suggested that, rather than imagining the figure as standing on tip-toe and about to take a step, we should imagine it aflutter in the air. That makes sense of the notable wings it once seems to have had (their attachment mechanism is still there), and of the strange and powerful iron bar which protrudes from its back; it looks perfect for receiving some kind of extensive bracket that might have held it aloft. The problem with this theory is that if some of the sculpture’s vices disappear from below, many of its virtues do as well: Its gorgeous left hand, carved with immaculate realism, is much less likely to be seen and noticed. Ditto for the lovely tops of its feet.

But what if the whole idea of a “correct” viewpoint for this statue gets its subject’s nature wrong: As a flying creature, it could never alight for long enough for any one viewpoint to dominate. Regardless of the practicalities of its actual display – even if the architecture around it once limited our access to a single position, for instance, or left the sculpture almost inaccessible – the only correct representation of this fluttering, evanescent, mobile being had to conceive of it as contingent and changeable.

Many details on the figure could never have been easy to see. What viewer could have gotten close enough to notice its delicately carved fingernails, or the lovely way its belly meets the muscular band above its pelvis? Anyway, we don’t have much evidence that Renaissance viewers gave works of art the endlessly attentive contemplation that some modern esthetes have come to value. In many a church or palace, there would not even have been enough light for such close looking. I believe that the never-seen subtleties of this and other Renaissance creations were put there because artists thought of themselves as world-builders first and image-makers second. Presence and completeness, rather than visibility, were the values that mattered.

But in this little spirit-being there may be yet another layer at work. If our spiritello is truly conceived as a creature endowed with the power of flight, we can’t only think of what we can see of him now. We have to imagine him swooping down to where his lovely hand and fingernails are revealed to us. That’s how his maker imagined him, fully, before giving him shape. (Image by Maggie Nimkin Photography, courtesy Andrew Butterfield Fine Arts)

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.