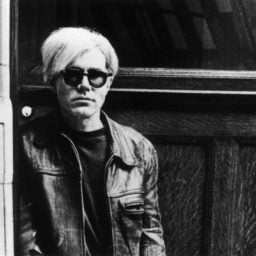

An iconic portrait of Marilyn Monroe by Andy Warhol soared to $195 million at Christie’s in New York on Monday, the second-highest result for an artwork at auction and the biggest test of the masterpiece market since March 2020.

Plummeting stocks in all major sectors, from banking to oil and gas, appeared to have minimal impact on the bidding at Christie’s Rockefeller Center salesroom. Nevertheless, the $170 million hammer total for Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (1964) fell short of its unpublished $200 million estimate.

After less than four minutes of bidding, the work was purchased by mega-dealer Larry Gagosian in the salesroom. He declined to say whether he bought the work for himself or a client.

The picture was offered along with 35 other lots from the estate of Swiss sibling dealers Thomas and Doris Ammann. All told, the sale generated $317.8 million, toward the lower end of its $284 million-to-$420 million estimate. Thirty-four out of 36 lots found buyers.

In a way, Gagosian’s purchase marks a return. The painting had been in the Ammann collection since Gagosian himself sold it to Thomas “out of my gallery on 23rd Street in 1986,” the dealer told Artnet News after the sale. “He didn’t even know it was in the gallery. He came to see something else, and he bought it on the spot.”

The evening was the first event in a two-week, $2 billion auction marathon, with more trophy art up for grabs than the market has seen in years. Testing the demand are a bevy of Rothkos, Monets, and Picassos, along with scores of flipped works by young artists.

The Marilyn result became highest price for an American artist at auction, wresting the title from Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose untitled canvas of a skull sold for $110.5 million five years ago.

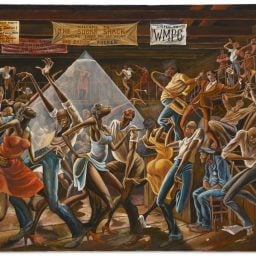

Andy Warhol, Flowers(1964). Image courtesy Christie’s.

All the proceeds from the Ammann sale will benefit charities providing urgent medical and educational care to children, according to Christie’s. It represents the largest philanthropic sale since the Rockefeller auction in 2018. The winner of the Warhol also has the opportunity to nominate the charities to which 20 percent of the Marilyn proceeds will be allocated, pending the foundation’s approval.

“I don’t think it’s about the stock market, that picture,” said Asher Edelman, who was a corporate raider before becoming an art dealer. “It’s a matter of someone in Abu Dhabi or elsewhere wanting it for a museum. There are no more Russians, but there are others.”

The priciest painting ever sold is Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, which fetched $450.3 million in 2017. With a presale estimate of $100 million, that work carried lower expectations than the Marilyn, which was the highest estimated work ever sold at auction.

“It’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance to own this painting,” said Alberto Mugrabi, art dealer and scion of the family that has the largest Warhol collection in private hands. “This is the ultimate. There’s nothing bigger than this.”

Warhol first painted Marilyn in 1962 on a smaller scale and returned to his famous and tragic muse twice more over the course of his career. The larger and more detailed format that he created in 1964 is considered the most desirable subset of the motif, which itself is the most desirable in Warhol’s oeuvre.

Shot Sage Blue Marilyn is one in a series of five that also includes versions in red, orange, and turquoise. Their title comes from an incident when performance artist Dorothy Podber shot the four stacked canvases with a revolver right between Marilyn’s eyes. (Only one version, the turquoise, was spared the assault.)

Cy Twombly, Venere Sopra Gaeta (1988). Image courtesy Christie’s.

The Ammann siblings bought the painting from Condé Nast mogul and mega-collector Si Newhouse 36 years ago in a sale brokered by Gagosian.

The “Marilyn” series has a storied market history. In 1998, Newhouse picked up another version of the painting—the orange one—for $17.3 million against a high estimate of $6 million. It was a watershed moment in the art business, which had never seen such a sum spent at auction. After Newhouse’s death in 2017, billionaire hedge-fund manager Ken Griffin bought that work privately for around $200 million, according to people familiar with the deal.

Other paintings in the series belong to newsprint mogul Peter Brant (who purchased the blue version for $5,000 in 1967), Steve Cohen (who bought the turquoise Marilyn for $80 million in 2007), and Greek magnate Philip Niarchos (who owns the red version).

“I have spoken to all the other guys who have these paintings and they will never sell them,” said Mugrabi, detailing various unprintable afflictions they would rather incur.

Brant attended the auction. When asked if he would part with his Marilyn he said, “No way. Never.”

The painting was the final lot of the Ammann sale, a smorgasbord of high and low, figurative and abstract, with a particular flair for appropriation art. It was a testament to the eclectic tastes of Thomas Ammann, who died in 1993, and Doris Ammann, who took over the gallery and ran it until her death a year ago.

Strong results for 1980s works by white male artists including Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi, Donald Baechler, Peter Halley, and Ross Bleckner defied prevailing trends, which have favored new, figurative paintings, with particularly strong competition for work by women and artists of color.

A small painting of three birds by Ann Craven, I Wasn’t Sorry (2003), also fetched a record $680,400, flying past the presale estimate of $20,000 to $30,000. A Mike Bidlo painting, Not Picasso (Bather with Beachball, 1932) (1987), sold for a Picasso-like price of $1.3 million, triple the conceptual appropriation artist’s auction record.

Gagosian was an active buyer during the sale, snapping up two paintings by Cy Twombly for $16.9 million and $21 million, and Franz West’s pink sculpture for $592,200.

But not every lot flew. A Sigmar Polke painting, estimated at $1.5 million to $2 million, and an all-black Brice Marden, estimated at $5 million to $7 million, failed to find buyers.

A large-scale but low-quality Basquiat, His Glue Sniffing Valet (1984), also struggled, hammering at the low estimate of $6 million ($7.3 million with fees) with just one bidder. It was the same for Lucian Freud’s Man Resting (1988), an unappealing nude, which hit the low estimate of $1.2 million ($1.5 million with fees). A large-scale work by The Bruce High Quality Foundation, once a hot art collective, hammered at $22,000, way below the low estimate of $40,000.

Asian bidding was thin throughout the sale, with only 10 percent of Asian participation, compared with 45 percent of American bidding, according to Christie’s. The Hong Kong salesroom was quiet when the Marilyn came up. And Middle Eastern bidders didn’t seem to materialize, either.

“The question is: Was Asia’s presence so low because of what’s going on in the world or because it wasn’t the material that they are chasing?” said art adviser Abigail Asher.

Tonight’s 21st century sale at Christie’s should help clarify the picture.