Market

In an Explosive Claim, an Art Dealer Says the Hermitage’s Fabergé Exhibition Is Full of ‘Tawdry Fakes’ From a Single Oligarch’s Collection

Art dealer Andre Ruzhnikov says that more than 20 works in the show are forgeries.

Art dealer Andre Ruzhnikov says that more than 20 works in the show are forgeries.

Simon Hewitt

A leading London-based art dealer has accused the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg of mounting a Fabergé exhibition featuring more than 20 “tawdry fakes” from the collection of Alexander Ivanov, a Russian oligarch with ties to Vladimir Putin and the Kremlin.

The explosive claim was made in an open letter to Hermitage boss Mikhail Piotrovsky by Andre Ruzhnikov, who has been buying and selling Fabergé for 40 years. In it, he accuses Piotrovsky of “insulting the good name of Fabergé, betraying your visitors’ trust, operating under false pretences, and destroying the authority of the museum you have been appointed to lead.”

“The Hermitage is the pride of Russia and belongs to the world’s cultural heritage,” Ruzhnikov wrote. “Your ‘Fabergé’ exhibition is dragging it through the gutter.”

This soldier figurine, which is being shown at the Hermitage as genuine Fabergé, has been dismissed by the director of the Fersman Mineralogical Museum in Moscow as a “low-quality modern replica” of Fabergé’s Soldier of the Reserve (1915) in his museum.

The allegations concern objects from the Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden, Germany, a private institution owned by Ivanov, that Ruzhnikov says are fake. The objects are in the Hermitage exhibition “Fabergé: Jeweller to the Imperial Court” (November 25–March 14, 2021).

Ivanov tells Artnet News that all the objects in the show were “selected personally by [curator] Marina Lopato, together with Hermitage museum restorers and other staff.” Lopato, a Fabergé specialist to whom the show is dedicated, died last July.

Piotrovsky, director of the Hermitage since 1992, has refused to respond to the charges. On January 13, he sent a blanket statement to the media referring enquiries to his catalogue preface, which states that “the authenticity of each fresh item that appears on the market can always be challenged and disputed… the consensus of the expert community is not easy to obtain.”

When Artnet News contacted Piotrovsky on January 26 inviting further comment, a museum press officer referred us to an article on a local website, Fontanka.ru, extolling Piotovsky’s “characteristic wisdom” in “anticipating the conflict.”

A recently colorized 1906 photo of Grand Duchess Anastasia that is allegedly the basis for the portrait on the Wedding Anniversary Egg.

At the center of the controversy is a Wedding Anniversary Egg ascribed to Fabergé and purportedly gifted by Czar Nicholas II to Empress Alexandra on Easter 1904 to mark their 10th wedding anniversary.

Since at least last spring, when DeeAnn Hoff, an independent Fabergé researcher from Oregon, published a critical assessment of the object in Fabergé Research Newsletter, its authenticity has been a point of contention.

In her article, Hoff claimed that four of the Egg’s miniature portraits depicting the Russian royal family were based on recently colorized archival photographs taken after 1904.

For example, the medallion of Grand Duchess Anastasia, according to Hoff, depicts her in a white dress with colored ribbons and bows. But according to several contemporaneous portraits by court miniaturist Vasily Zuev (1870–1941), Anastasia wore a dress of pure white, ribbons and bows included. Her image on the Wedding Anniversary Egg medallion appears to come from a colorized version of a black-and-white photo taken in 1906. That image is freely available online.

Another anachronism, Hoff writes, concerns the Egg’s Nicholas II portrait. The Czar is shown wearing just four of the five medals that bespangled his uniform from 1896 onwards. Hoff believes the image is based on an outdated photograph from 1894, before the addition of his fifth medal. The miniature portrait on the Egg also wrongly shows one of the Czar’s medals—the Order of the Dannebrog—with a blue ribbon rather than the red-and-white colours of the Danish Flag.

The portrait of Grand Duchess Maria on the Wedding Anniversary Egg of 1904. It appears to be based on a 1910 photo of Maria that inspired court miniaturist Valery Zuev’s Maria medallion for Fabergé’s Fifteenth Anniversary Egg of 1911 (below).

Ivanov—who shot to prominence in 2007 after bidding a record £9 million on the Rothschild Fabergé Egg, which was presented to the Hermitage in 2014 by Vladimir Putin—supplied Artnet News with 13 documents purportedly substantiating the provenance of the Wedding Anniversary Egg and three other items in the Hermitage exhibition dismissed by Ruzhnikov as modern fakes: a Hen Egg dated in the catalogue to 1898; an Alexander Nevsky Egg dated to 1904; and a soldier figurine dated to 1917.

One of the documents is a typed list of valuables for export drawn up by Soviet authorities in October 1932 that includes an item Ivanov says is the Wedding Anniversary Egg, described as a “white enamel egg with a bouquet of flowers.” Yet this item is listed with accession number 17555, long cited by Fabergé scholars as referring to the 1901 Basket of Flowers Egg acquired by Queen Mary, wife of British King George V, in 1933. That Egg is now in the Royal Collection.

Court miniaturist Valery Zuev’s Maria medallion for Fabergé’s Fifteenth Anniversary Egg of 1911. Courtesy the Fabergé Museum, St Petersburg.

The description corresponding to number 17555 in the inventory for the Kremlin Armory museum in Moscow—a leading depository of Fabergé material—is “so detailed there is not the slightest chance it can be identified as the so-called Wedding Anniversary Egg of 1904,” says Kremlin Armory archivist Tatiana Tutova.

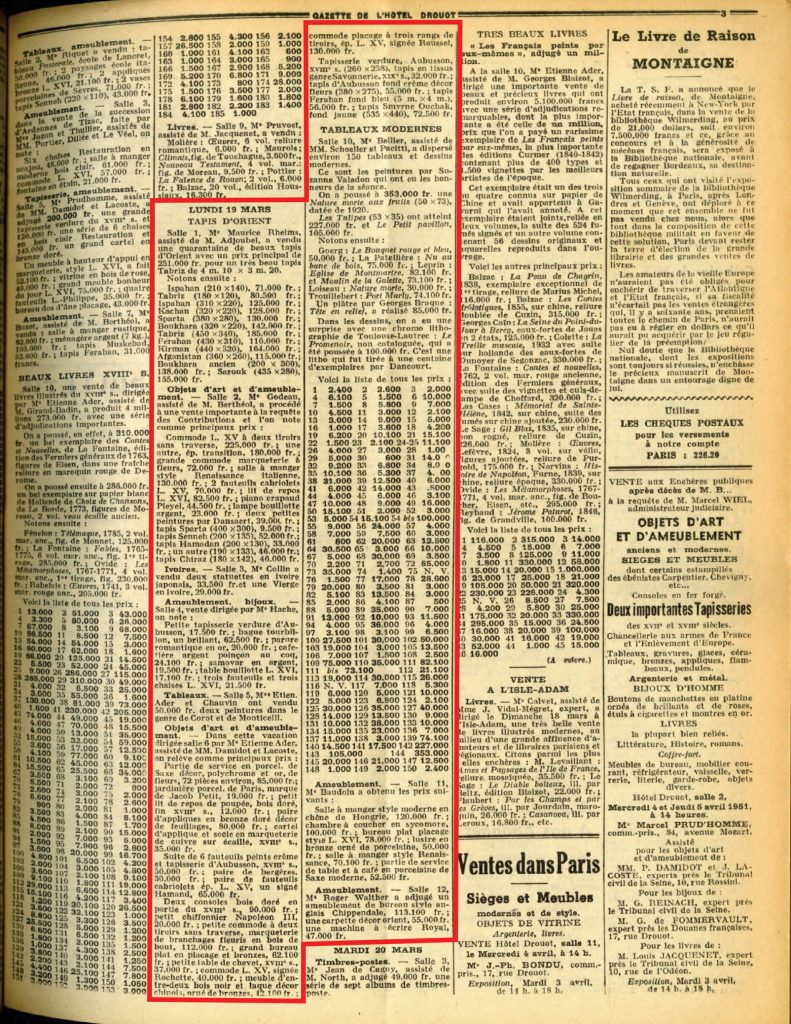

Ivanov also claims his Wedding Anniversary Egg was auctioned by Maurice Rheims in Paris on March 19, 1951. Yet the copy of the catalogue entry Ivanov has furnished as evidence is in English, not French. And no such sale was recorded in that week’s Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot, the weekly journal providing an obligatory official record of every auction held in the French capital. (The Hôtel Drouot is the central Paris auction venue where, until 2000, virtually all Paris auctions were legally required to be held.)

The Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot record indicating the Hôtel Drouot sale of March 19, 1951, was dedicated to oriental rugs.

When Ruzhnikov announced that he had ascertained from the Drouot archives that the sale staged by Maurice Rheims on March 19, 1951, was devoted to Oriental carpets, Ivanov claimed the Egg was auctioned at another Paris venue. He did not say where, nor has he provided a copy of the catalogue’s cover or contents.

The institutions lending items to the Hermitage show have also raised eyebrows.

The Hermitage’s own Fabergé holdings are relatively modest and, alongside the suburban St Petersburg palaces of Pavlovsk and Peterhof, the only other lenders to the exhibition are the Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden, the Russian National Museum in Moscow—another private museum owned by Ivanov—and the Museum of Christian Culture in St Petersburg, owned by Konstantin Goloshchapov, a close ally of Putin’s. The goal of these private museums, Ruzhnikov argues, is “to legitimize counterfeits and enhance their market-value by exhibiting them in the Hermitage.”

Ruzhnikov and Hoff are not the only ones to criticize the show’s contents. In a letter sent to Piotrovsky by Pavel Plechov, director of the Fersman Mineralogical Museum in Moscow, Plechov says the show’s purported Fabergé soldier figurine is a “low-quality modern replica” of Fabergé’s Soldier of the Reserve (1915) in his museum.

Conspicuously absent from the exhibition’s partners is the Fabergé Museum set up a mere mile away from the Hermitage in 2013 by Viktor Vekselberg to showcase the 190-piece Forbes Fabergé collection he acquired for a reported $100 million in 2004. (Ruzhnikov was instrumental in negotiating that sale.) No senior Fabergé Museum personnel had even visited the exhibition as we went to press, two months after its opening.

This 19th-century tiara, sold at Christie’s on November 26, 2014 for just £74,500, is now presented at the Hermitage as a work by Fabergé.

The accusations against the show and Ivanov’s collection are being made against the backdrop of a robust dark market for forged Fabergé goods.

“There’s always been a lot of Fauxbergé on the market,” Ruzhnikov says. “But the fight against it is picking up speed.” A recent Christie’s catalogue, for example, included a silver desk clock assigned to Fabergé and granted a £30,000 to £50,000 estimate. Ruzhnikov, in an auction preview posted on his personal website, dismissed it as a “piece of garbage.” Christie’s withdrew the item before the sale, citing “authenticity concerns.”

Ruzhnikov says there have been multiple instances of items affixed with Fabergé hallmarks and repackaged as authentic. One of the four diamond tiaras in the Hermitage show, owned by Ivanov and again attributed to Fabergé, passed through the hands of London jewellery dealer Humphrey Butler, who tells Artnet News he bought it from an art advisor in December 2012. He then sold it to one of London’s leading wholesalers, Anthony Landsberg, in early 2013.

“Nothing at the time indicated that the jewellery was of Russian origin,” Butler says, adding that he was “amused” to see a tiara sold by Christie’s for £74,500 in November 2014 resurface as a “Fabergé” item in the Hermitage exhibition. The auction house’s sales catalogue blandly described it as “an antique sapphire and diamond tiara, circa 1900, with early 19th-century elements.” No Fabergé hallmark was apparent.

“It is inconceivable that Russian Empresses, with the unmatched Russian crown jewels at their disposal, would demean themselves with composite low-quality tiaras of this type,” said a prominent London Fabergé dealer, speaking off the record.

One of the most spectacular fakes Ruzhnikov has encountered is a gold and nephrite “Imperial Empire Egg” purportedly commissioned by Nicholas II in 1902 that was offered to him for $2 million in 2005. At the time, it contained a portrait of Alexander III.

When a Russian imperial inventory surfaced in Denmark in 2015 referring to an “egg with gold mounts on two nephrite columns” with portraits inside of Prince Piotr Oldenburgsky and Nicholas II’s sister, Olga, the portrait of Alexander III was replaced by a modern double-portrait of the couple, Ruzhnikov says.

He was re-offered the Egg in 2018. The new price? $55 million.