Auctions

Faded Photos Bought for $2,200 at an Estate Sale Turn Out to Be Two Rare Stieglitz Works Stuck Together

A rare and pristine platinum print was hiding behind a faded Alfred Stieglitz print auctioned at a Connecticut estate sale last year.

A rare and pristine platinum print was hiding behind a faded Alfred Stieglitz print auctioned at a Connecticut estate sale last year.

Sarah Cascone

An eagle-eyed collector bought a framed photo at a tiny Connecticut auction house for just over $2,000 last year. He was surprised—and overjoyed—to find that inside the frame, there were not one, but two original rare 19th-century platinum prints by the famed American photographer Alfred Stieglitz.

Three similar prints of the same image are in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The new find brings the total number of extant prints to five—including a newly discovered one in flawless condition.

Photographer and professor Jeff Sedlik bid $2,200 to take home the work, which variously goes by the titles A Venetian Courtyard, A Venetian Well, and A Well, Venice, at a December 2021 estate sale at Schwenke Auctioneers in Woodbury, Connecticut. He beat out just one rival bidder.

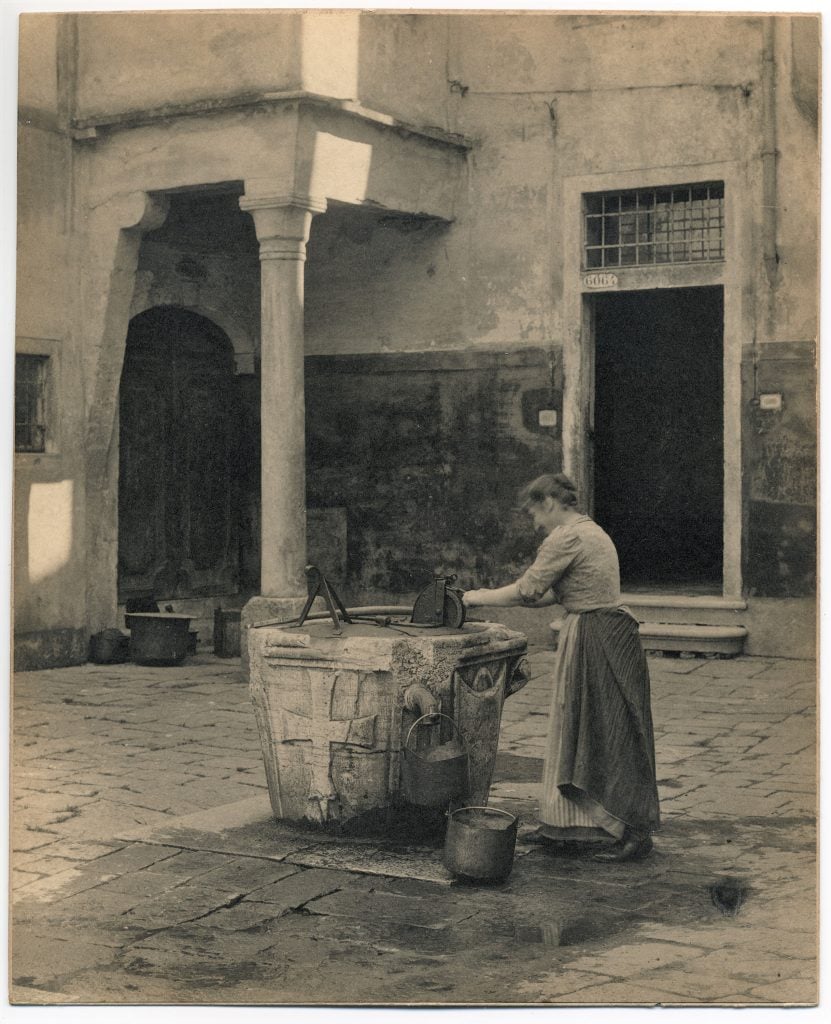

Once he got the work home, Sedlik discovered a second print of the image hidden behind the faded one he had just bought.

“When I opened the frame for the first time in 120 years and saw that there was a second print, a perfect platinum print with the richest tones you’ve ever seen, I was just staring at it. I could not believe it,” Sedlik told Artnet News. “I don’t even have a word for it. It was really incredible.”

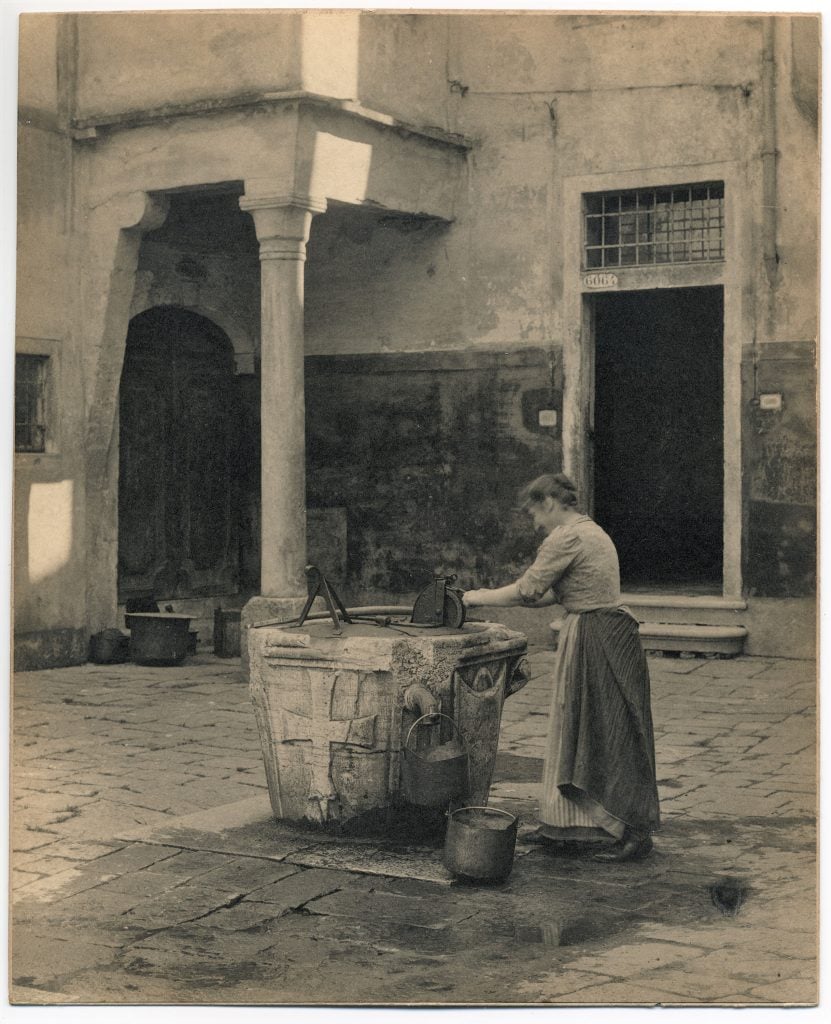

Alfred Stieglitz, A Venetian Courtyard (1894). Jeff Sedlik purchased this faded platinum print at auction and discovered a second perfectly preserved print of the image hidden inside the frame.

A professor of photography at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California, Sedlik immediately recognized the faded image when he spotted it in the online catalogue for the sale—even though the artist’s name was misspelled. Over the years, he had included the very same shot, of a woman in a long skirt drawing water from a well at Venice’s Campiello Santa Marina, in his coursework to illustrate the ways in which Stieglitz and other late 19th-century photographers drew on painterly traditions.

“When I saw it, I thought, no photography collectors were going to be at this auction, and most people who would recognize it wouldn’t spend money on such a faded print—but I could overlook that because it’s such an important photograph,” Sedlik said.

The picture dates to Stieglitz’s honeymoon trip to Europe with his first wife, Emmeline Obermeyer, in 1894, when he made what would become some of his most celebrated pictures of the 1890s.

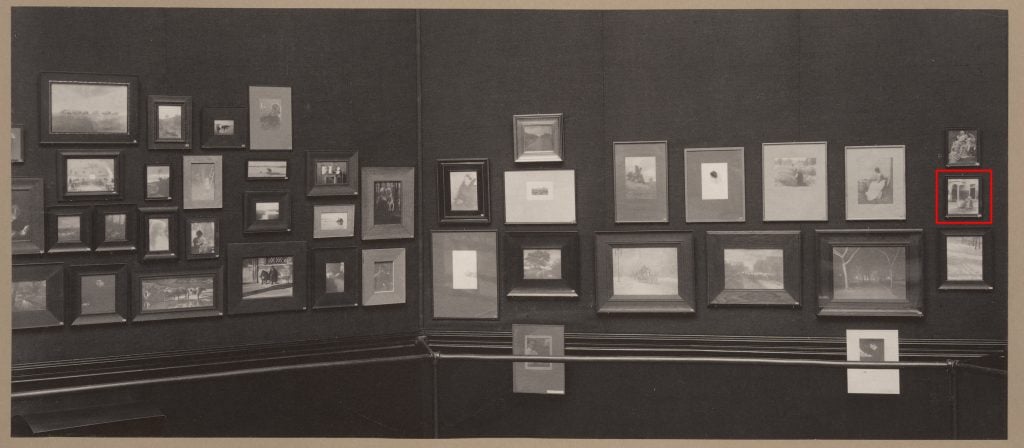

Alfred Stieglitz’s A Venetian Courtyard (1894) on view at the 1899 Philadelphia Photographic Salon exhibition. Photo courtesy of the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York.

There are three prints of the image, in which Stieglitz experimented with different crops, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which owns copies of every print the artist had in his possession at the time of his death. There’s also one known lantern slide of the composition, printed on glass, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Until now, no other versions of the image were known to survive.

“Stieglitz, like many photographers of the time, didn’t make many prints of his photographs, as there was very little market for them,” said Sarah Greenough, senior curator and head of the department of photographs at the National Gallery. (She has been in touch with Sedlik about his recent discovery.)

What makes the find even more surprising is that many of the works that Stieglitz did print didn’t survive the artist’s lifetime.

“Stieglitz destroyed at least 90 percent of his negatives and prints—the guy would light fire to everything and burn it. He just wanted to move forward artistically. I think the way that he put it was ‘make room for the new,'” Sedlik said. “That makes his prints, especially from the 19th century, really rare—they had to escape his grasp.”

The work is not only significant due to its rarity, but also due to its place in art history, made at a time when photography, previously considered a mechanical process, was beginning to be accepted as art in its own right.

The photo the Sedlik purchased at auction came from a family in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, and was one of hundreds of lots on offer in the estate sale, which mostly featured furniture and decorative objects.

The auction house hadn’t taken the time to open the frame ahead of the sale, and Sedlik recognized there was a good chance the print up at auction was a mere reproduction. Nevertheless, he decided it was worth the risk, since a platinum print by Stieglitz would normally be way out of his price range, and this could be his only chance to own one.

Alfred Stieglitz’s A Venetian Courtyard (1894) on view at the 1899 Philadelphia Photographic Salon exhibition. Photo courtesy of the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York.

Looking closely at the object, Sedlik has started to come up with a theory about how it traveled from the artist’s studio to an obscure Connecticut auction house.

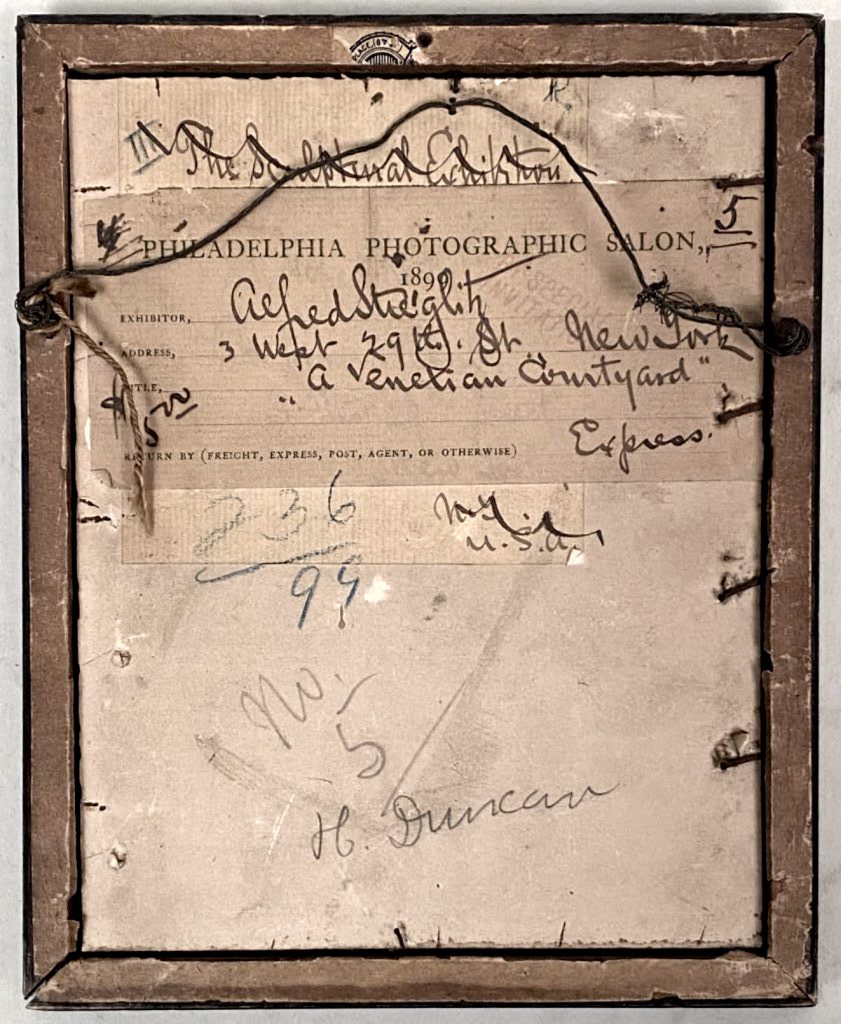

The back of the photo bears an entry label for the 1899 Philadelphia Photographic Salon, a major photography exhibition that helped establish the medium, as well as Stieglitz’s address. (He had judged the inaugural 1898 show, and exhibited at the follow-up event by invitation.) Adding to the evidence is the remains of a logo on the frame that is part of the label of George F. Of, Stieglitz’s longtime framer.

There is a photograph of works on view in the show that clearly shows A Venetian Courtyard on view. It was numbered 283 in the exhibition records—a number still affixed to the corner of the frame when Sedlik bought his work at auction. The photo has a price of $15 written on the back. There’s also a clue as to who the buyer was, thanks to an inscription of the name “H. Duncan.”

Stieglitz may have included two prints instead of one inside the frame because he was using very thin paper, and wanted to make sure the work would lie flat. He was known to mount prints on the back of one another. But you might be surprised to learn why the print on top was so faded.

“Even today, platinum prints are really admired and respected because the tonalities are incredible, with this rich and subtle variation—and typically, they don’t fade,” Sedlik said.

The back of the frame of Alfred Stieglitz’s A Venetian Courtyard (1894), showing a label for the 1899 Philadelphia Photographic Salon exhibition. Photo courtesy of Jeff Sedlik.

But photography was also an experimental medium, often involving mixing in other substances, like mercury, during the development project to achieve the desired effect. “If you didn’t do it right, you could have problems down the line with fading,” he added. The prints have not yet undergone a full battery of chemical tests, but Sedlik believes both would have been treated with mercury—and that Stieglitz made some kind of mistake creating the faded one.

There’s no telling how much the newly discovered images are worth, but Stieglitz’s record at auction is $1.47 million, for a 1919 palladium print of Georgia O’Keeffe (Hands), according to the Artnet Price Database. It sold at Sotheby’s New York at the “Important Photographs from the Metropolitan Museum of Art” sale in 2006.

The artist’s 19th century work, commands considerably lower, yet still-hefty prices, topping out with the £192,000 ($380,440) sale of the 1893 print Winter – Fifth Avenue at Sotheby’s London. New York photography dealer Hans Kraus estimated Sedlik’s find could be worth a price in the mid-five figures.

Sedlik has stored the print in a secure, climate controlled facility for safekeeping. “My budget is limited,” he said, “so I go down the rabbit hole looking at auctions where other collectors don’t go.”