Art Fairs

‘When You’re Home, You Hit a Home Run’: French Dealers Make Steady Sales at FIAC as Foreign Galleries Rush to Establish Spaces in Paris

Paris is quickly becoming the most important city in Europe for the art trade.

Paris is quickly becoming the most important city in Europe for the art trade.

Nate Freeman

On Wednesday morning, as a crush of elegantly dressed VIPs stepped off the Champs-Élysées and streamed into the soaring Beaux-Arts masterwork that is the Grand Palais for this year’s edition of FIAC, it was easy to forget that, not so long ago, this was not a must-attend stop on the global art fair circuit. In fact, it was a regional fair in a collecting backwater.

“When I started, the fair was collapsing,” said Kamel Mennour, who opened his gallery in 1999 and is now one of the city’s most beloved art dealers. “The first fair I did was 2000, and it was the third world. It was completely nothing. When you said you were doing FIAC, they said it was bullshit.”

Oh, how the times have changed. Now, with Boris Johnson struggling in Brussels to negotiate with the European Union to avoid a no-deal Brexit, Paris has emerged as the most likely candidate to become the art-market powerhouse of continental Europe. The red-carpet rollout of David Zwirner’s new outpost brought some serious oomph to the week’s run of gallery openings, leading a string of newcomers to the city’s circuit, including White Cube (which will open an office) and Pace (which is said to be looking for a location).

A Cosima von Bonin sculpture at Gaga. Photo: Nate Freeman.

Some dealers tried to downplay the idea of competition between the two cities, saying that, ideally, a fair such as Frieze London, the city’s biggest contemporary art expo, can co-exist with a surging FIAC. (Many of those dealers, not incidentally, have galleries in London that they are understandably concerned about.) “If there is a cultural renaissance in France and in Paris—I believe this is the case—it has nothing to do with the as-yet-undetermined effects of Brexit,” FIAC director Jennifer Flay told artnet News earlier this week.

But for others, it’s a tad hard to ignore the political turmoil a short Eurostar ride away. And regardless of what caused it, the rise of FIAC has made for a jaunty mood underneath the Grand Palais’s famous vaulted windows.

“The city is buzzing,” said Thaddaeus Ropac, who first opened in Salzburg in 1983, and who now also has galleries in Paris and London. “People are moving to Paris, and I just hope it doesn’t get too expensive, because then artists couldn’t live in Paris.”

Ropac—who opened his first Paris space in 1990 and now lives here most of the time—was standing in the middle of a gallery where Robert Rauschenberg’s Everglade (Borealis) (1990) sold in the opening hours for $1.7 million. When asked if the Brexit anxiety, plus the arrival of galleries such as Zwirner, have made for a more bustling fair week this year, Ropac responded, emphatically, “Oh yes.”

“Already Monday and Tuesday in the gallery, it was like, wow,” Ropac said. “We haven’t seen this kind of intensity ever. Paris is in the middle of a good wave.”

Zwirner was upfront about the Brexit-related reasons for his hasty entree to the Parisian scene, and in the opening hours sold a bunch of works out of his booth, contributing to a two-day haul that began when top-shelf stuff found buyers in the backrooms of his new gallery.

At FIAC, the gallery presented a three-person booth and sold six works by Lucas Arruda for between $75,000 and $80,000; three works by Sherrie Levine for between $320,000 and $750,000; and many new works by Wolfgang Tillmans for between $35,000 and $150,000.

The homegrown dealers who’ve been here for decades are finally reaping the rewards of having put down roots in what’s become a picture-selling bonanza. Galerie Templon has been around since Daniel Templon opened a space in 1966 at the age of 21. (His was the first French space to show American Minimalists and Conceptualists such as Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, Carl Andre and Joseph Kosuth.)

But gallery director Anne-Claudie Coric recalled how, during the recession of the 1990s, Daniel suffered so badly he had to downsize his space and cut back on staff.

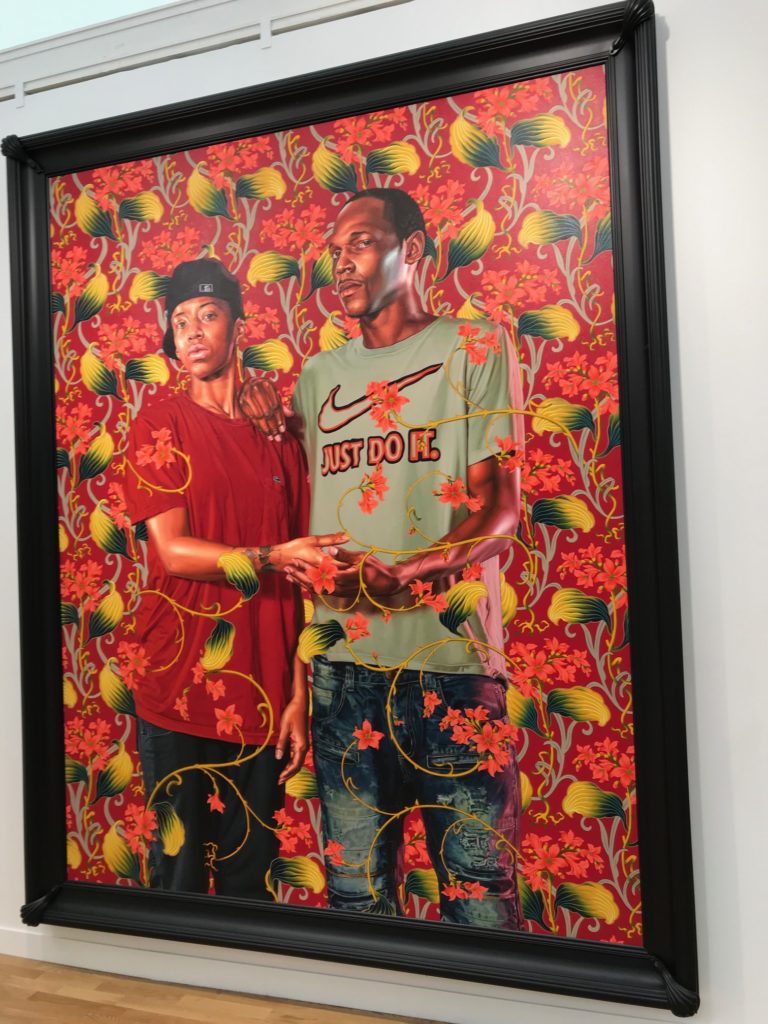

A Kehinde Wiley painting at Galerie Templon. Photo: Nate Freeman.

Now, his is one of the oldest Paris galleries at a fair teeming with international collectors. The gallery sold a gigantic work by Kehinde Wiley for $350,000, which it will swap out tomorrow for another Wiley of the same size. The gallery expects it to sell quickly, too.

“FIAC has really sped up in the last few years,” Coris said. “Now, with all the talk of Brexit, what’s going to be the next capital of the European art world? Paris is the natural choice.”

FIAC is a solid bet for dealers such as Olivier Babin, the proprietor of Clearing in Brooklyn and Brussels, who was showing on the Grand Palais’s top floor, where slightly younger galleries hawk wares by younger artists. (Other highlights up there included some typically mind-bending Pop-Surreal paintings by Jamian Juliano-Villani at JTT; a neon Cosima von Bonin cigarette sculpture at Gaga, a steal at €35,000; and Eliza Douglas’s hilarious and scathing copies of Josh Smith’s polarizing palm tree paintings. The Douglas “Josh Smiths” are $20,000. A new Josh Smith painting was sold out of the Zwirner viewing room for $250,000.)

Not only is Babin French, many of his artists are from this neck of the woods, and several are showing this week at various institutions around the city. Marguerite Humeau is at the Pompidou as a nominee for the Marcel Duchamp Prize, Meriem Bennani is at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, and Lili Reynaud-Dewer is in a show at the recently reopened Paris Museum of Modern Art. What’s more, Babin said he sold a 2015 painting by Harold Ancart for $320,000, perhaps at the high end for any work in the upstairs section of the fair—or any section, actually. (To compare, a new, primary-market Ancart sold at Zwirner for $150,000.)

“This is home, and when you’re home, you hit a home run,” Babin said.

Eliza Douglas’s riffs on the work of Josh Smith. Photo: Nate Freeman.

Should Brexit go through on its scheduled date of October 31, Hauser & Wirth, one of the world’s biggest galleries, will no longer have a gallery in the European Union. (A space in Menorca, Spain, is scheduled to open in 2020.) And while partner Marc Payot emphatically denied that they were opening a space in town (despite a comically loud chorus of rumors to the contrary), he did report that there is a role for the gallery in Paris—at FIAC, which has become an exponentially more important version of its former self.

“FIAC was not, quality wise, that great ten years ago,” Payot said. “Now it’s a fair with great quality of dealers, who are also bringing works that are very good.”

Accordingly, a few works found buyers in the first minutes of the fair, including Louise Bourgeois’s I Want To Be Sure You Love Me !! (2008) which sold for $1.75 million; Mark Bradford’s Painting 6 (2019) which sold for $1.2 million; and a gorgeous new work by Rita Ackermann, Mama Nagyika, that sold for $165,000.

Pace, the New York-based mega-gallery that has six spaces across the US, Europe, and Asia, has also been rumored to be looking for a space in Paris. Yet when asked for details, gallery president Marc Glimcher said: “I’ll tell you ‘no comment’ in French: N’ai pas du commentaire.”

Glimcher did say that the gallery had basically sold out its booth in the first hours of the fair—”we sold almost everything, and I didn’t have to do anything”—and that there was quite a fight between collectors trying to get their hands on works on paper by Yoshitomo Nara.

“I lost some friends over it,” Glimcher said.

The reason for the scrum might have been that, as Glimcher explained, the gallery refused to raise Nara’s prices after a crazy-high record of $24.9 million was set for a painting by the artist at Sotheby’s Hong Kong earlier this month. (Meanwhile, as I reported last week, Nara’s doodles on a bar in the East Village neighborhood of Manhattan are now worth millions, and my story has made headlines around the world.)

“No price changes here at the Nara store,” Glimcher said, noting that the drawings sold for between $50,000 and $90,000. “We didn’t pay attention to the silliness in Hong Kong.”

Philip Guston’s Curtain and Sea (1979) was on view at the Hauser & Wirth booth at FIAC. © the Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy the Estate and Hauser & Wirth.

Down the aisle from Pace, Lévy Gorvy was doing FIAC for the first time since Dominique Lévy and Brett Gorvy joined forces in 2017 to form the gallery. The pair doubled down on France by bringing a giant work by the the 83-year-old French master Martial Raysse from the collection of the Princessa Catherine Aga Khan to FIAC. But European director Victoria Gelfand-Magalhaes—whom the gallery poached from Gagosian earlier this year, sparking talk of further continental expansion—denied that they were opening in Paris, despite acknowledging a bunch of solid reasons why they should.

“Paris is picking up steam, and with collectors such as Pinault and Arnault here, there’s a real energy,” Gelfand-Magalhaes said. “And Dominique is Francophone because she’s Swiss, and she has a house here… I mean, I would love to have a gallery in Paris. Who wouldn’t?”

While there were no announcements Wednesday, Coric, the Templon director, thinks it’s a matter of time before another mega-gallery takes the temperature and decides that Paris is the future of the art market in the European Union.

“Hauser has been speaking about opening a space in Paris for 15 years, so that’s probably something that will happen,” Coric said.

And then the director of one of Paris’s oldest contemporary art galleries noted that, given the country’s history, foreign powers should be cautious before expanding across the border.

“We don’t like anything that looks imperialistic,” she said.