Art Fairs

Great Art Isn’t Always What It Seems: 5 Works at Art Basel That Deserve a Closer Look

The best works at the blue-chip art fair can be tricksters.

The best works at the blue-chip art fair can be tricksters.

Andrew Goldstein

At Art Basel, the premier souk of global fine art, appearances can often be deceiving. A work that looks simple can be staggeringly complex; what seems to be ancient can actually be cutting edge. A photograph, you learn, is not always really a photograph. Here are several works of depth and historical richness that are testament to the rewards the fair offers those who take a pause to look, listen, and learn.

SARKIS

Galerie Nathalie Obadia – Paris

Born in Istanbul in 1938 as the son of an Armenian butcher, Sarkis Zabunyan became drawn to art at a young age when he happened to see a reproduction of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, went to study art in France, and began specializing in conceptual works that explore the idea of color as a market of identity and difference. In an era when his countrymen were struggling with the history of the Armenian genocide, an atrocity that the Turkish government refuses to admit to this day, his treatment of simple pigments—often impressed upon surfaces as fingerprints—took on a political weight. At the fair, Sarkis presents an artwork that literally measures this weight: enclosed in a handsome wooden box, a precision scale hangs two fingerprints (one green and one red) in the balance, and finds them equal.

Today counted among the greatest Armenian-Turkish artists, Sarkis was part of the group that received the Golden Lion for the 2015 Armenian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, which was curated to memorialize the centennial of the genocide. Based in Paris, the artist has recently been working on a series of fingerprinted windows—his take on stained glass—for a church in Aix-en-Provence, and two of those were on offer at the fair. Each of his pieces were priced at $31,000.

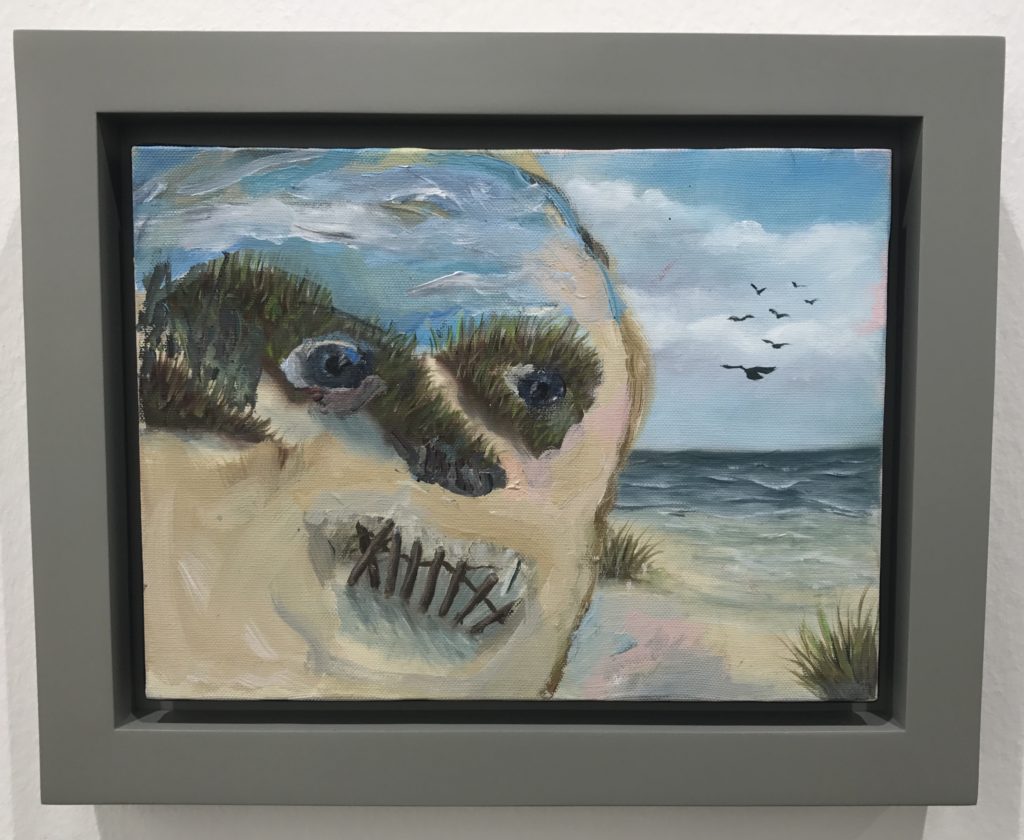

MARGOT BERGMAN

Corbett vs. Dempsey – Chicago

Now in her early 80s, the artist Margot Bergman is having a late-career renaissance. Having studied at the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1950s, Bergman devised a style of painterly collaboration in which she would find landscapes in flea markets, hang them in her house for long enough to get a sense of their hidden inner identities (so to speak), and then paint faces on them. Sometimes comic, sometimes haunting, these works gained some acclaim—she won the Purchase Prize from the Art Institute—and in the 1970s the New York dealer Allan Stone signed her to his gallery. For some years, Bergman split her time between her family in Chicago and her burgeoning career in New York, spending six months in each place and alternating the roles of mother and wife and independent artist. The death of her brother in Chicago, however, compelled her to return home for good, and she put her art career on hold.

In the mid-‘90s, when her children were grown, she resumed the brush. Working with the highly regarded Chicago gallery Corbett vs. Dempsey for over a decade now, she has since developed her style away from the thrift-store paintings to a new form of collaboration: she invites an assistant into her well-worn bungalow studio to make a few marks on canvas, and she riffs on these to create a full composition. Their key, as with her earlier pieces (which recall the work of Asger Jörn), is the way the initial design forces her to improvise within a given context—something her dealers compare to the way she colored outside the lines of conventional motherhood in the ‘70s.

Ravishing and mysterious, her lush paintings found a fan in the New York dealer Anton Kern when he saw them in a group show, and he gave her a solo show as well. Now the MCA Chicago has started collecting her work, and the Los Angeles dealer Susanne Vielmetter will soon bring a solo show of her work to the West Coast. Bergman continues to be prolific to this day, emailing her Chicago dealers an image of a painting every week, appended with a “Love, Margot.” And it’s a good thing, too. At the fair, all but two of her paintings had sold by Thursday afternoon, priced between $7,000 and $25,000.

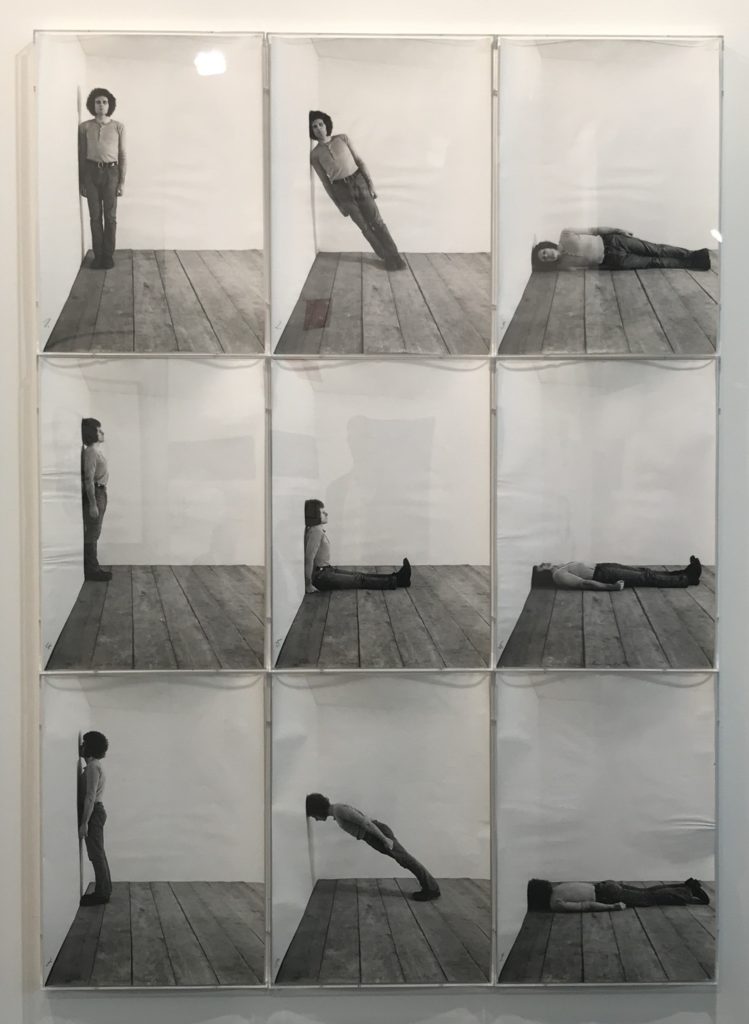

KLAUS RINKE

Kicken – Berlin

The influential performance artist Klaus Rinke began working with his body as a form of sculpture in the late 1960s, positioning himself in various settings in ways that made the most of his gangly physique and large round tuft of brown hair, then documenting it. The work that arose, like this suite of photographs charting a performance at the Lisson Gallery in 1970, were filled with the era’s spirit of creative freedom; for the piece, he laid down boards of raw wood on the floor of the pristine white gallery space and fashioned himself into lines in concert with the wall, forming compositions that mirror the hands of a clock—a recurring motif of his work. Rinke’s proposition of the body as sculpture found powerful adherents: when he had a solo exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1973 of his photographs, it was the sculpture department that organized the show.

For decades, the artist worked at the art academy in Düsseldorf, promulgating his insights to a new generation. This year, at Art Basel, Berlin’s Kicken Gallery has included his work in two places, displaying this piece at the front of the booth (priced at $90,000) and also in the Unlimited section, where photographs of the artist maneuvering his arms around his face into “112 gestures of the upper body” blanket one large wall.

EDWARD KRASIŃSKY

Foksal – Warsaw

A pioneer of the Polish avant-garde who shared a Warsaw studio with the movement’s leader, the painter Henryk Stażewski, Edward Krasiński was interested in expanding upon the innovations of Modernists like Picasso and Braque to further liberate painting from the flat picture plane, bringing it out into the space of the world. In the mid-1960s, he hit upon this breakthrough piece: a canvas painted ashen black, sliced with a crescent through its middle and bent into a sculpture. He gave it red-tipped spikes—like gory fangs—and a tail whipping across its center.

Looking a bit like a primordial Surrealist predator stalking through the protoplasm, the artwork, titled Composition in Space (1964), is an important transitional piece for the artist. He would go on to entirely change his style, while still engaging with the three-dimensional architectural environment, by installing groups of abstract geometric paintings that he connected into intricate “interventions” via long strips of blue Scotch tape. His work is now widely prized by curators, and Krasiński—who passed away in 2004—will be the subject of a career retrospective opening at the Stedelijk this month and then touring to Tate Liverpool.

This early sculptural painting, which sold for more than $200,000 at the fair, is a totem from the period when he was innovating his artistic approach alongside Stażewski. The studio in which they worked has now been preserved as an invitation-only museum, with no component allowed to be moved.

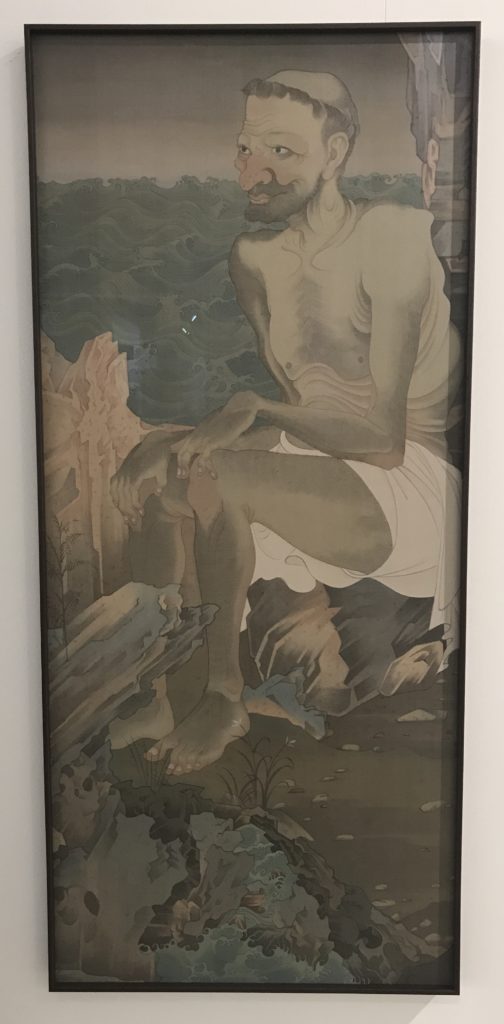

HAO LIANG

Vitamin – Beijing

Beckoning collectors to the booth of Beijing’s Vitamin gallery, this exquisite painting resembles a treasure from the golden age of Chinese art history—but it is not what it seems. In fact, far from being the work of a wizened master lost to time, this painting was made by a millennial named Hao Liang, a rising star of contemporary Chinese art.

While the other artists of his generation have been experimenting with the latest technology and other avant-garde art approaches, the 33-year-old Hao—who is known as “the scholar” among his peers—has dedicated himself to absorbing the full panoply of techniques from Chinese art history. The way he pushes this style of art forward is in the subject matter, which creates a teasing link with Western history.

This painting, for instance, arose as a playful reaction to Ingres’s 1856 masterwork The Source, a portrait of a naked young woman in a trickling grotto, pouring an amphora of water over her shoulders as the very picture of voluptuous feminine fertility. Hao decided to transliterate this into the Chinese tradition, only as its opposite: a painting of a frail old man sitting on a rock, looking out onto a wide open body of water.

There are other inversions, too: Hao painted his portrait on silk, using tiny brushes to create multilayered washes of color in the mode of traditional landscape painting. But whereas a Chinese landscape would render any figure as a diminutive element within a far larger vista, Hao crops out much of the environment to focus in on the man.

Hao’s portrait, also titled The Source, is priced under $100,000, and observers of the Chinese contemporary art scene say his career is just beginning to take off. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art recently acquired his work, and a 12-foot landscape on silk of his can be found in the Arsenale section of the Venice Biennale,