French economist Françoise Benhamou is plugged into the economies at play in the art industry. Chairwoman of French think-tank Le Cercle des économistes and a professor at Sciences Po university, among other higher education institutions, her latest book, Le don dans l’économie (The gift in the economy, co-written with Nathalie Moureau), looks at the gift economy, from the establishment of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to the outpouring of donations for the reconstruction of Notre-Dame cathedral, and patronage towards museums.

As a recession looms before the end of the year, we caught up with the economist on what the wider financial headwinds could portend for the art market.

What impact do you think the current economic downturn will have on the art market?

The art market has a capacity to resist economic situations. Sometimes it goes against the tide and can be regarded as a safe haven. Nevertheless, economic studies have also shown that after a certain amount of time the art market is impacted too. What strikes me is that the most speculative segments, such as NFTs, have already suffered.

How do you think Covid-19 has affected the art market?

While buyers continue acquiring works of very high quality and at high prices, small galleries face difficulties to survive. We still don’t have reliable data on how the profound transformations of the Covid-19 pandemic could have affected the art market longer term. A lot of people said that fairs were threatened and raised questions about aerial transport, increasing costs due to inflation and tourism becoming more expensive. What we’re facing today is a combination of the financial situation due to Covid (and to geopolitics), an economic crisis to do with inflation and energy, and an ecological crisis.

Courtesy of Françoise Benhamou.

What do you think the implications are?

Participating in fairs will be more costly for galleries. All players are under pressure to be more ecologically correct. The increasing trend of people working from home and perhaps traveling less could lead to artworks circulating in different ways. Will collectors continue to travel in order to spend two days at a fair? Or will they use the internet more to discover artworks and select fewer trips?

Some people will go back to their old ways. But younger collectors who are working remotely, who are the ones most concerned about the world’s future, might completely change their behavior and ask galleries and auction houses to make their practices more ecological.

Why do economists look at what’s happening in the art market to anticipate societal trends?

The art market is a trailblazer, a world where creativity is a raw material, and it’s a pioneer in enacting models such as digital practices. Very often, the phenomena that we observe in the cultural world will later be found in the general economy. This can be seen from people renouncing a standard job in favor of working on a project-basis to developing online platforms for buying artworks.

Your book questions how patronage is distributed, the social and cultural sectors being the largest recipients. What recent observations have you made?

The search for patronage opens up a double competition, on the one hand between culture and other “great causes,” and on the other hand within the cultural world between different disciplines or fields–lyrical arts, theater, fine arts etc.—or between establishments. During crises, many sponsors maintain their support, considering that it is more necessary than ever. The available data bear this out. But this dual competition is getting tougher, and the most innovative or less visible projects, as well as the smaller or less well-known establishments, are struggling to find private money.

What are your thoughts on the “buy one, give one” (BOGO) phenomenon in the U.S., whereby some galleries are compelling collectors to buy an artwork to donate to a museum in order to buy a work by the same artist for their own collection?

Museums have had ambivalent relationships with the market for a long time. Raymonde Moulin mentioned this in her groundbreaking book on the art market [L’Artiste, l’institution et le marché, published in 1992]. The American initiative is interesting. It’s a way for artworks to enter museums. It’s also a symptom of this sort of complicity between the market and institutions: by bringing an artwork into the museum, one increases the price of an artist’s work on the market.

Furthermore, there can be a perverse effect: asking collectors to buy two works instead of just one can drive some buyers out of the market.

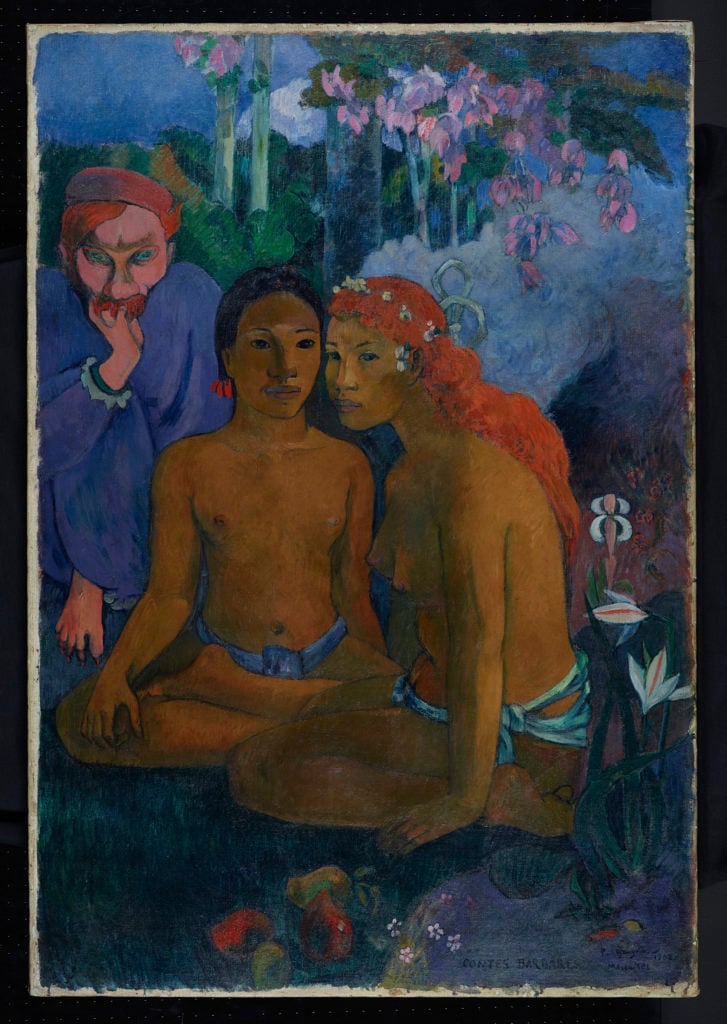

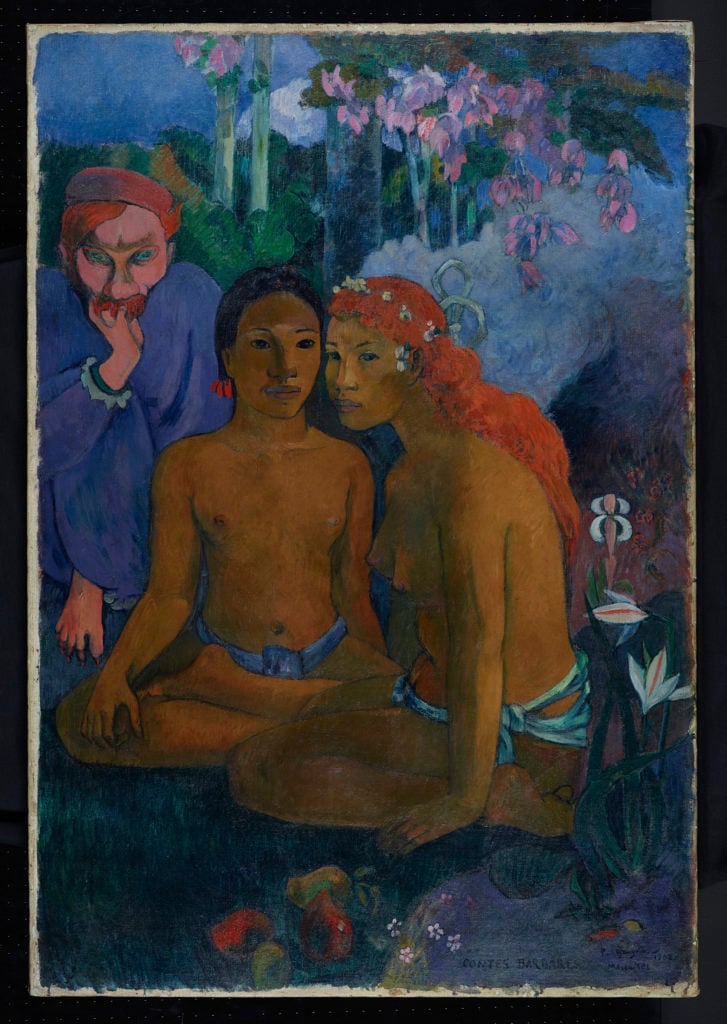

Paul Gauguin Contes barbares (1902). Courtesy of the Museum Folkwang, Essen.

Which other issues concern you today with regard to the art world?

There are two movements that worry me greatly because they could make the art world more fragile. The first is wokeism, which could call into question living or late artists, such as Picasso and Gauguin, based on today’s norms. The second is populist movements. In some countries in Eastern Europe and in Brazil, there are governments that will be less supportive to artists; museum directors will either be revisionists or be told that the exhibitions they want to plan don’t conform to what the government wants.

How important do you think the art market is for the French government of Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne?

A few months ago, I wrote with two other economists a note about culture for the CAE, France’s council of economic analysis, which was presented to culture minister Rima Abdul Malak. She was very sensitive towards the issue of making culture more democratic. There’s a public program called Mondes nouveaux [New Worlds, with a €30 million budget to support 430 creators] that supports artists, but the art market isn’t among the government’s priorities, probably because one thinks that it’s working well with advantageous tax rates.

Stock image of a woman looking at the Marie de’ Medici painting cycle by Peter Paul Rubens at the Louvre in Paris. Photo by

Una Laurencic, from Pexels.

What impact is Brexit having on the London art market and the Parisian market’s renaissance?

What will weigh more on the U.K. is the Russia-Ukraine war. Anyway, Brexit is a message of being closed-off, which is the opposite of the art market that’s open and that contributes towards modernizing societies thanks to its promotion of cultural diversity. Brexit makes transactions more complex. I think there’ll be a fall in transactions in Britain but Paris won’t take anything away from the English market. If we consider the French art scene, what’s happening is remarkable. There’s a desire for France to find its place again, thanks to the opening of the Collection Pinault, the Fondation Louis Vuitton and the new space for the Fondation Cartier being inaugurated next year. France had been very nostalgic about the place that it had lost, and we can observe a kind of revival recently.

What are your views on a cultural boycott of Russia?

I’m always very ill at ease about boycotting artists. One should be careful about isolating Russians any more than they already are. The idea of banning great Russian authors like Dostoevsky and Tolstoy is nonsensical. It’s clear that part of the art market will be closed off from Russia which is terrible for Russian artists. There’s also the risk of censorship and political lawsuits for artists. Many artists will migrate.

How are changes in the Asian economy, due to Covid-19, the crashing property market and political turmoil in Hong Kong, affecting the art market internationally?

China is closing in on itself, and the geopolitical and economic issues are affecting our relationship with China. The place of China in the global economy and its rising power seems less obvious than before Covid-19. Even if we take into account the market share of Asia–in 2021, the contribution of China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and South Korea represents approximately 40 percent of the global art market–we will observe probably the formation of large “tectonic plates” at the global level, with fewer relations between them.

How do you envision the art market’s future, from widening inequality and rising global wealth to emerging art capitals?

Inequalities are much greater in the U.S. than in France, for instance. To be frank, inequalities are never bad for the art market. When people have a lot of money, they buy art. But we need to open up the game to find tomorrow’s collectors and enable upper-middle class people to buy art.

European art capitals are very heterogeneous. Lille and Marseille both successfully developed permanent projects when they became European capitals of culture in 2004 and 2013 respectively. For instance, Marseille’s candidacy wasn’t just artistic but involved the old port renovation and improving traffic routes.

Recently, France’s culture ministry has invented the designation of “French capital of culture”, following the initiative of Bernard Faivre d’Arcier [in response to former French President François Hollande calling upon the artistic community to propose dynamic projects for cities outside Paris]. I was on the first jury in 2020. Nine cities competed. The winner was Villeurbanne, French capital of culture for 2022.

Fewer cities entered the second competition in 2021 because the culture ministry gives €1 million, which is insufficient for a year-long event aiming to change a city’s image. This is something that needs to be reviewed: too much public money for Paris compared with middle-sized cities.

How do your students feel about society today?

They’re worried, often unhappy and are questioning societal models. The big cities are over; young people are thinking of living elsewhere and differently. The relationship to art might rebuild itself from the bottom up, through young people’s practices towards an appetite for culture leading us towards visiting exhibitions in museums and galleries.

Perhaps we’ll consume culture through local places where one will be able to find art, discuss with artists, have coffee etc. What’s important is cultural porosity between different forms of creation – going to the theater and seeing an exhibition on the same occasion. Tomorrow’s world is about giving the young people who feel excluded from the art world, and don’t go to museums and galleries, the possibility to do so. To fulfill that task, we need to encourage artists to visit schools in difficult areas and create artists’ residences in the suburbs.

What are the implications of all of these issues for museums?

I participated in a blockchain conference where museums were talking about reinvention. Modern and historical museums were asking whether they should put on less costly, less international exhibitions. I’m ambivalent about that. Although more effort should be made to produce exhibitions more modestly, such as reusing materials, the art world needs to be open towards the exterior and have major exhibitions featuring artworks from all over the world. Big exhibitions are important for a museum’s history.

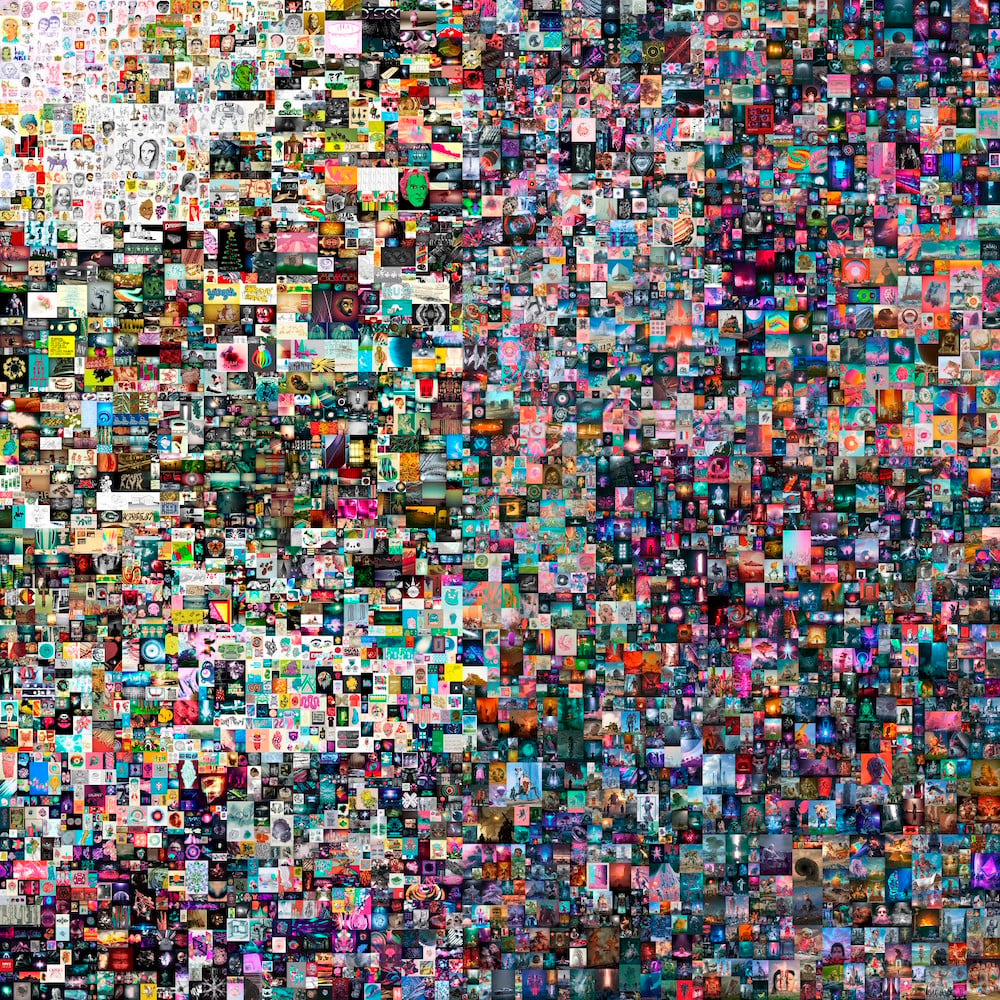

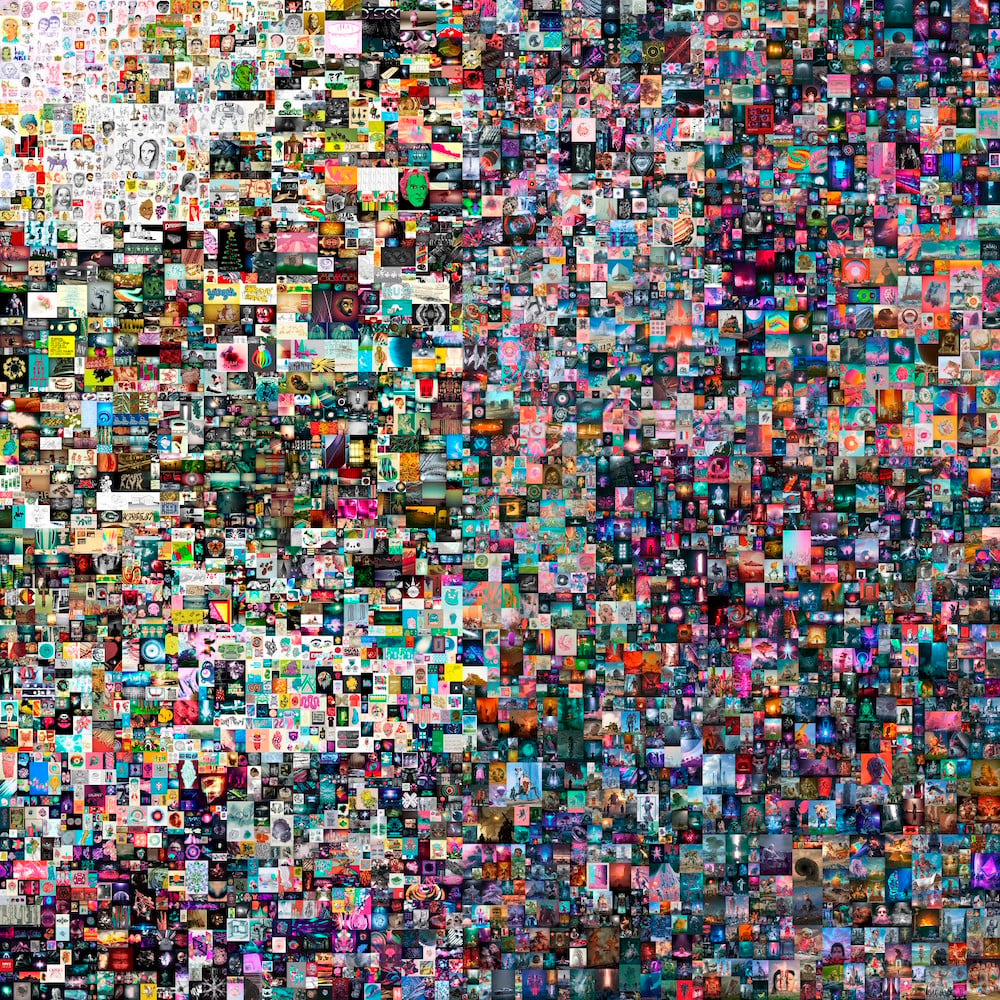

Beeple, Everydays – The First 5000 Days. Courtesy of the artist and Christie’s.

Earlier this year, you gave a talk on NFTs at the Académie des Beaux-Arts. What are your overarching views on NFTs?

Everything that opens the market towards new experiences and can attract new buyers is interesting, but one should never fall into a trap. Part of NFTs was ultra-speculation, such as Beeple [whose work, The First 5000 Days, sold for $69 million in 2021], and that speculative bubble is about to explode. But artists making digital native NFT artworks seem interesting. I’m circumspect about museums making NFTs based on artworks in their collection; it could be an additional revenue source but I doubt they’ll make as much money as one might imagine.

A finance bill is being proposed in France to qualify NFTs as artworks. What are your thoughts on the status on NFTs?

At the moment, the fiscal definition of artworks doesn’t include NFTs. The nascent market of NFTs needs to be better regulated through taxation and intellectual property laws, and identity verification regarding cryptocurrency in order to prevent money-laundering and reduce risk. NFT smart contracts should conform to existing juridical measures on a national level. What’s complicated is that there are also NFTs in the fields of games, luxury goods and sport, and NFT artworks need to be identified as such.

‘Le don dans l’économie’ is published by Éditions La Découverte.