Art Fairs

Future Fair Debuts in New York With an Experimental Co-Op Model—and Dealers Say It Has Delivered

Going on now through Sunday, Future Fair operates like a co-op, sharing profits with participating galleries.

Going on now through Sunday, Future Fair operates like a co-op, sharing profits with participating galleries.

Taylor Dafoe

As suggested by its name, Future Fair was conceived as a newfangled kind of expo, one modeled more like a co-op: profits are shared, finances are transparent, and what’s good for the individual is good for the collective.

It’s a nice idea, but in a landscape dominated by mega-fairs that operate more like big-box supermarkets, the long-term sustainability of that model remains an open question. And it’s one that’s hanging over the Starrett-Lehigh Building in New York this week, as Future Fair, founded by Rachel Mijares Fick and Rebeca Laliberte, finally stages its inaugural in-person edition. (The fair was originally scheduled to debut last year, but the pandemic pushed the event online.)

So, will this experiment actually work?

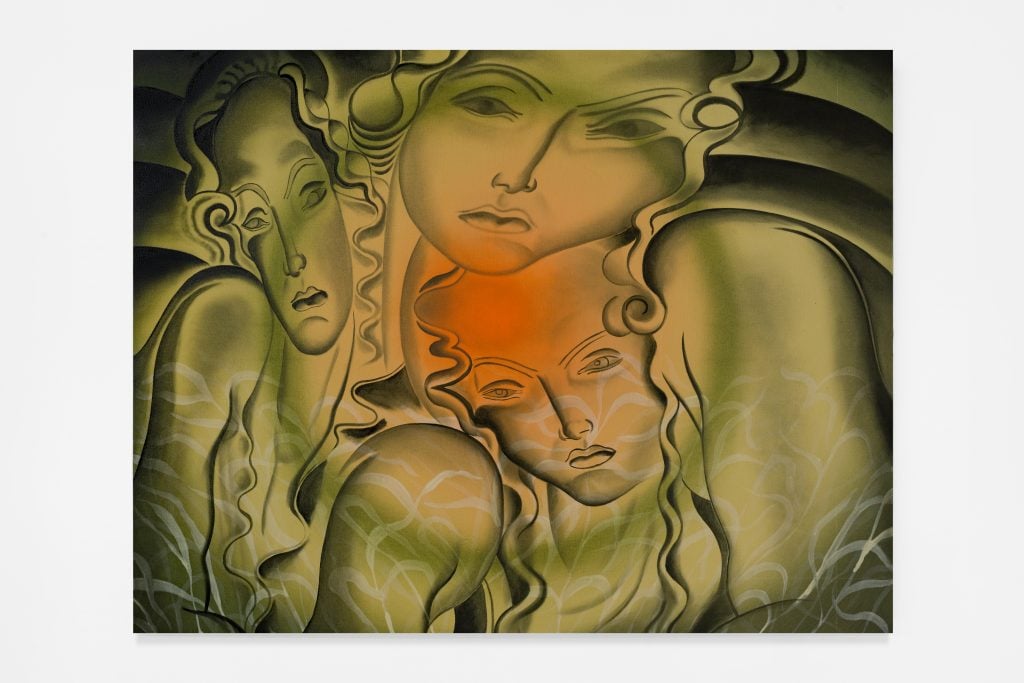

Ojo Ayotunde, Alright (2021). Courtesy of Nyama Fine Art.

Among the 34 exhibiting galleries—25 percent of which are owned by people of color and 50 percent of which are owned by women—initial impressions are optimistic, even if actual sales have been slow-going so far. (After a VIP day, the fair opened to the public today.)

“So far, it’s been wonderful,” said Russell Tyler, a painter-turned-gallerist who opened the space Sunny NY earlier this year. “People are discovering the works of the artists. That’s the main goal, to find people who are interested in the work, even if they don’t purchase something now.”

As far as events like this go, Future Fair is on the smaller side, which may earn it tick marks in both the pro and con columns. The humble size of the fair offers a welcome respite from the overcrowded Armorys and Friezes of the world, but it also limits its offerings. Turn the corner after what seems like just a couple of booths and you may be surprised to suddenly find yourself at the exit door—no more art.

“I love that it’s small,” said New York dealer Asya Geisberg, noting that the city has long needed a more modestly scaled prestige fair. “You get so much more as a viewer.”

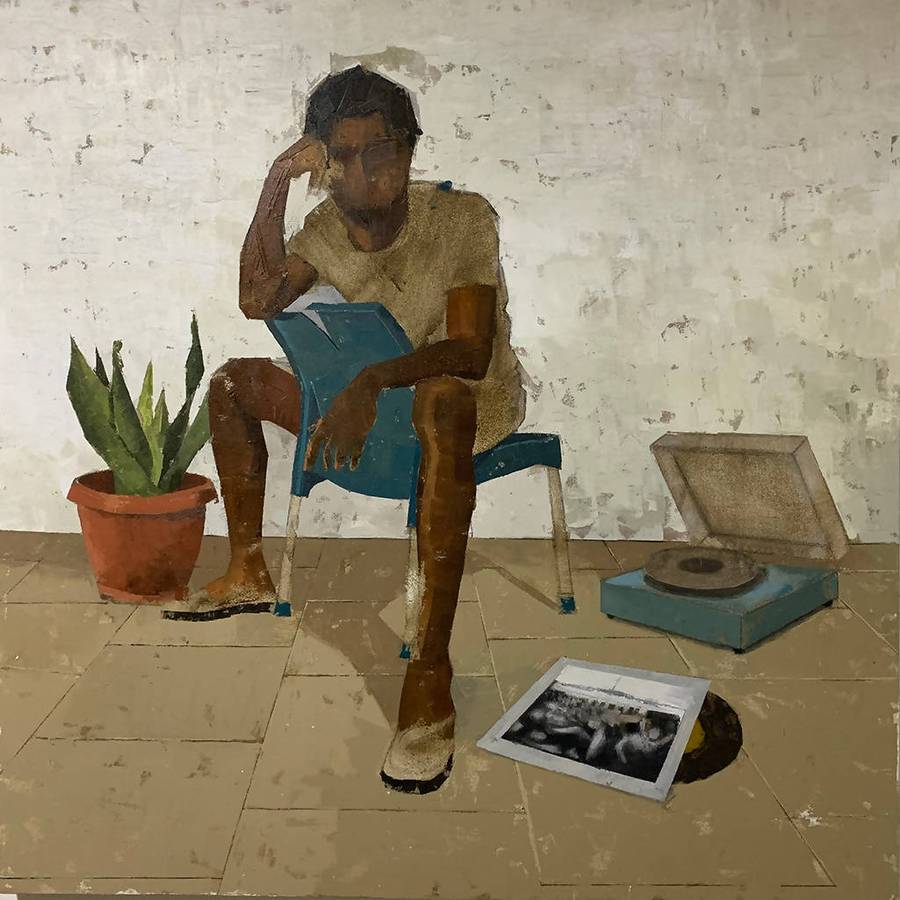

Angelina Gualdoni, The Physic Garden (2021). Courtesy of Asya Geisberg Gallery.

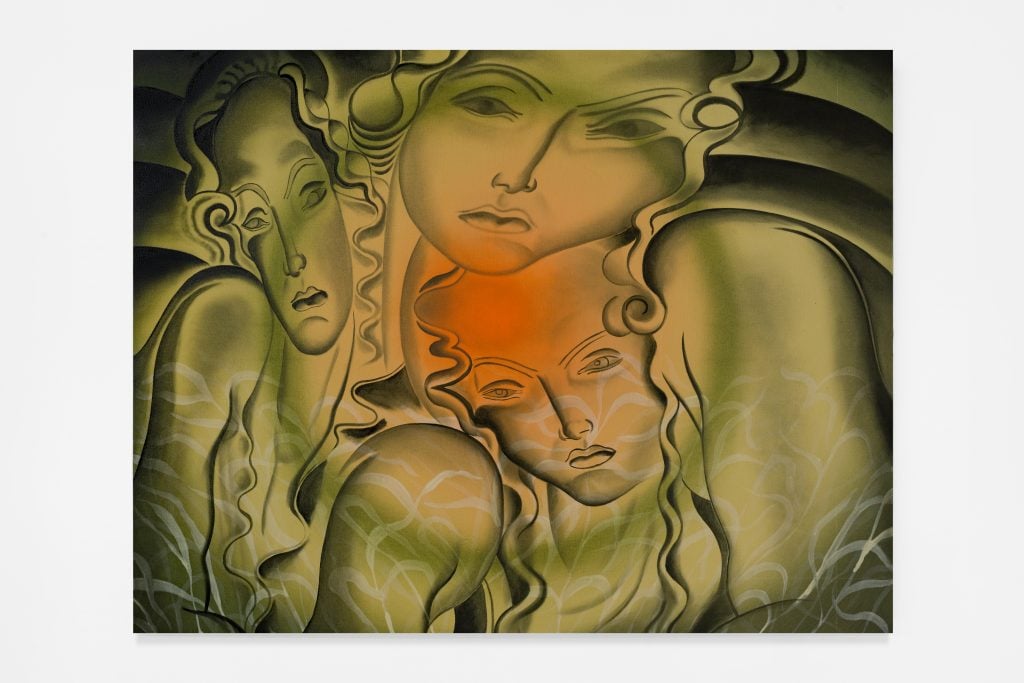

Still, “quality over quantity” has been the fair’s mantra since it launched, and there’s a lot to like here. Ojo Ayotunde’s contemplative, Noah Davis-esque self-portraits at Nyama Fine Art (Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts) come to mind, as do Amie Cunat’s graphic botanical paintings at Dinner Gallery (New York). A joint presentation of trippy paintings from Jacopo Pagin and sardonic ceramics by Cary Leibowitz at New Discretions (New York) packs one of the expo’s better one-two punches.

Funnily enough, the fair’s profit-sharing model doesn’t seem to have been a huge draw for dealers. “I barely even paid attention to that,” said John Pollard, founder of Richmond, Virginia, gallery ADA. Owning a small gallery in a small market, Pollard sales aren’t the aim of the fair; it’s more about meeting potential collectors.

“To me, sales are a consideration, but they’re not the only consideration,” echoed Pollard’s booth-mate, Asya Geisberg. “To me it’s more about what this fair is doing, building up an audience and an idea.”

Geisberg said that the sense of community and collaboration was the big appeal for her. “Like with everything in life, you put in more you get more.”

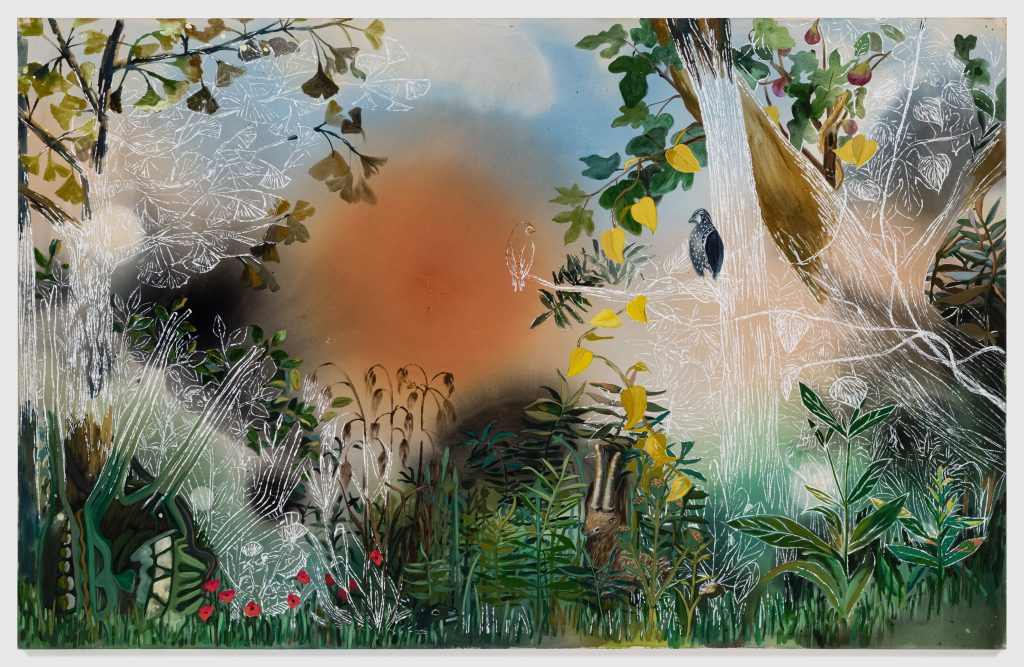

Brian Belott, Untitled, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Mother Gallery, Beacon, NY.

“I don’t know if there will be any profit this year, but it’s a nice gesture,” Paolo Oxoa, founder of the Beacon, New York-based Mother Gallery. (Oxoa is also opening up a new space in Tribeca later this month.) “And because we’re invested in that way, they also share with us a lot of what they’re thinking and planning, their numbers—information that most fairs keep to themselves.”

For Oxoa, who was among the first dealers to sign on to the fair before the health crisis, that sense of personal touch has been a big reason why she’s stuck with the fair.

“[The founders] said they were going to do these things, and through the pandemic, which has been such a challenging time, they’ve stuck to those promises. That means a lot to me,” said Oxoa. “I’m proud to be here.”