Market

Germany Is Giving Out Tens of Millions of Euros to Cultural Workers Hit by Its Faltering Economy. Some Say It’s Not Nearly Enough

Although the country has been praised for its efforts, many in the art world say they need more relief.

Although the country has been praised for its efforts, many in the art world say they need more relief.

Kate Brown

Last month, after the German economy started to sag following a nationwide coronavirus lockdown, the country’s federal and state governments sprang into action and issued tens of billions of euros to their citizens in an effort to prop up businesses and help individuals pay their bills.

The city-state of Berlin, Germany’s art capital and home to at least 20,000 artists, issued €1.3 billion in loans and handouts to small business owners and freelance workers, directly benefitting small galleries, arts organizations, artists, and other cultural producers. With minimal information—little more than a mailing address, tax ID, and banking details—150,000 applicants sought funding online and woke up the next day with anywhere between €5,000 and €14,000 in their bank accounts. International and local press outlets were delighted.

“There will be enough for everyone,” Berlin’s culture minister, Klaus Lederer, assured the state, and a flood of positive press coverage celebrated German efficiency and ingenuity.

But just two weeks later, the excitement is starting to wane. Artists say there is troubling fine print attached to new federal funds being doled out, which don’t take into account the full needs of culture workers in quite the same way as the first rush of local money in Berlin did. What’s more, recent tax hikes on art sales are doubly crippling galleries as they struggle to stay afloat.

“We have been hit with the loss of Berlin Gallery Weekend, Art Cologne, and now Art Basel,” says the dealer Johann König. “I have 40 staff to take care of. Why does the German government think that art dealers are bad?”

A view from the 2019 edition of the now-defunct Art Berlin fair. © Clemens Porikys.

In mid-March, the federal government and several German states presented separate plans to bail out businesses and freelancers. Monika Grütters, the country’s culture minister, pledged that cultural workers would be able to tap into a €50 billion federal stimulus package: individuals would be eligible for up to €9,000 in individual one-time grants, and small businesses could apply for up to €19,000 in individual one-time loans.

Meanwhile, the state government in Berlin promised upwards of €100 million—a number that grew to €1.3 billion within weeks—in the form of €5,000 one-off grants and €15,000 one-off loans. Both federal and state programs included other benefits such as tax deferrals.

But due to the ad hoc nature of the bailout programs, many did not grasp their various rules and stipulations. According to the results of a survey published last week by the Berlin Artists’ Association, 32 percent of 1,744 Berlin-based respondents said they did not understand the differences between the two programs. The distinction, in fact, is important: applicants have only been allowed to apply either for federal or state relief, but not both.

Furthermore, those who applied for funding from the state of Berlin benefitted from the government’s slashing of red tape. Applicants needed only very limited documentation; did not need to prove any loss of income; and could use government funds to pay for costs of living a well as running their businesses. Money was delivered within days, and fraudulent claims are expected to be sorted out at the end of the tax year.

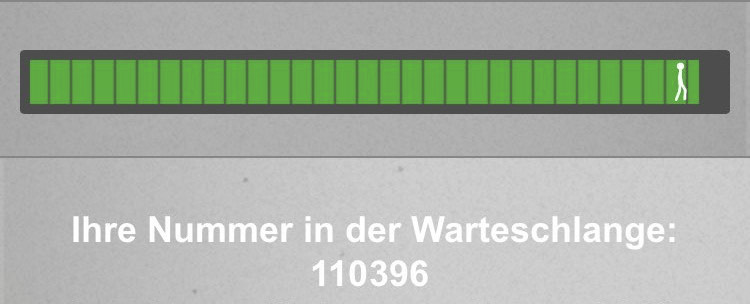

“Your number in the line is 110,396.” A screenshot from an online application for Berlin state stimulus grants, courtesy artist Zuzanna Czebatul.

On the other hand, the federal program—which is now the only one available after the Berlin pot ran dry on April 6—has many more hurdles. Anyone applying without a German passport must present a special document issued by a state office no more than four weeks ago, which could be difficult—or even dangerous—to obtain amid the lockdown.

Crucially, federal funding can also only be used for business costs, not for personal expenses such as health insurance contributions or residential rent. But for artists and other creatives, the boundaries between personal and business expenses are sometimes not so clear, and some are complaining that the application requirements fail to take into account the realties faced by cultural workers.

Some say that if artists remain unable to apply for federal relief, they will be pushed into controversial welfare programs, which demand that applicants participate in meetings and prove that they are looking for work. The program is designed to keep people uncomfortable enough to edge them back into employment. (Its slogan translates its dual motives: “demand and support.”)

“Many [federal stimulus] applications from artists are currently being rejected,” according to a report in Süddeutsche Zeitung, noting that artists are being referred to welfare programs. That fact is a “slap in the face of every freelancer,” Berlin music council president Peter Stieber told the newspaper.

Although Berlin has been widely lauded for its state program, it has run into its own issues. According to the survey from the Berlin Artists’ Association, just over 33 percent of respondents said that they did not apply for money because they were missing information, and nearly 20 percent were missing the necessary identification. Sixty percent of the applicants who were not able to apply for myriad reasons said they needed the grants to secure their livelihoods.

Local organizations are now lobbying the government to create a special program just for artists. A petition signed by more than 400,000 people and directed at Germany’s finance minister, Olaf Scholz, is demanding universal basic income in place of loans and tax deferrals. Another petition, signed by 300,000 people, is asking for the government to better acknowledge the unique working conditions for creatives. Organizations like the Berlin Artists’ Association are also asking the government to loosen rules on what it counts as business expenses.

“Many of these artists live on the edge of subsistence anyway, but the current mass cancellation of events threatens to push them over this edge,” one petition reads, noting that current regulations requiring applicants to prove a loss of income leaves out too many people. “Society may be able to do without cultural life for some time. But if it does so for too long, we could end up in a situation with nobody left to revive it.”

So far, however, the pleas have fallen on deaf ears.

“Even if there is no special program just for culture, the federal government’s aid program is especially tailored to the needs of the creative milieu,” Grütters, the culture minister, insisted in an interview last week with Der Spiegel.

Michael Werner’s booth at Art Cologne.

Meanwhile, dealers are facing their own troubles. The German government has confirmed that lockdown restrictions will be extended into May, meaning that the economy has at least several more weeks of near-total stasis.

And while some see Germany’s relatively cool-headed management of the crisis as a sign that it could come out the other side as an art-market center, there are numerous hurdles to get over.

“The emergency aid program was a very welcome and successful measure that enabled the galleries to survive the initial period. However, it will only bring temporary relief,” says a spokesperson from the Federal Association of German Galleries and Art Dealers. “The art market is already under extreme strain due to a multitude of new laws and regulations. Long-term measures are therefore needed to help galleries and art dealers and thus also the artists and the German art market.”

Among the relatively recent laws that are hitting dealers hard is a 2014 measure that raised taxes on art sales from 7 to 19 percent. On top of this, there is a wavering 4.2 percent to 5 percent tax that supports health and pensions benefits for artists, which dealers must pay when compensating their artists. While many EU countries have a substantial tax on art (it is 20 percent in the UK and 21 percent in Holland), German dealers face a unique situation of combined tax of up to 24 percent.

For the time being, most of these costs are being shouldered by galleries, says Berlin-based art dealer Sebastian Klemm. “One can easily calculate the annual amount that is lost in our balance, and which cannot be invested in employment, more ambitious projects, building up stock, or to cover the heavy rent increases of the last four to five years.” Dealer and art advisor Marta Gnyp adds that the double tax is effectively a “state subsidy financed by dealers.”

Carolin Leistenschneider, a dealer at the Contemporary Fine Arts gallery, says such problems have paralyzed businesses—and scared away collectors.

“As a consequence, art collections can’t grow anymore in Germany and are being placed or moved abroad,” she says, adding that the taxes on art sales are much more favorable in the non-EU country of Switzerland (8 percent), which is home to Art Basel. In Austria, taxes on art are 13 percent.

No one Artnet News spoke to is asking for the artist’s social insurance, a safety net that ensure artistic livelihood in what is otherwise a financially precarious field, to be recalled. A reduced tax rate is the best solution, says the spokesperson from the Federal Association of German Galleries and Art Dealers. “German cultural policy can now finally do something meaningful, necessary, and fair for the art market.”

But it is unlikely that a tax break is in the cards, especially in light of the economic crisis, which is leading to deep deficits for local and federal governments. On top of that, reduced tax revenues are bound to hurt cultural organizations and events that benefit from government support in the years to come.

“Collapsing tax revenues in the near future and increasing debt will put massive pressure on cultural funding,” Olaf Zimmermann, the managing director of the German cultural council, wrote in a letter to the Berlin Artists’ Association.

In the meantime, the country’s art world remains in limbo: while varying bailout programs have helped, they won’t solve every problem.

In an op-ed written by Kristian Jarmuschek and Birgit Maria Sturm from the German Association of Galleries and Art Dealers, the dealers put the situation in stark terms: Germany’s emergency programs, they wrote, “are beneficial for the time being, but in the end amount to nothing more than the proverbial drop in the ocean. Operation successful—patient dead?”

[April 17: This article was updated to include tax rates for Austria and the UK]