Market

What Does ‘Follower of Raphael’ Really Mean? Here’s a Glossary for Understanding the Mysterious World of Old-Master Attributions

The Old Master market can be confusing. We're here to help.

The Old Master market can be confusing. We're here to help.

Daniel Grant

Imagine flipping open an auction catalogue and reading the following description: “Old painting, looks Italian (or something).” Not particularly appealing, is it? But call the author of that same picture “Follower of Raphael” or “Manner of Raphael,” and you might find your interest piqued. Perhaps, you might think, it could be an unknown Raphael—or as close to one as you will ever be able to afford.

This is all by design. Auction houses engage in complex attribution language to lure in buyers while avoiding potential liability. “Major artists’ names attract more bidders than minor artists’ names,” said Andrew Fletcher, senior director of Old Master paintings at Sotheby’s.

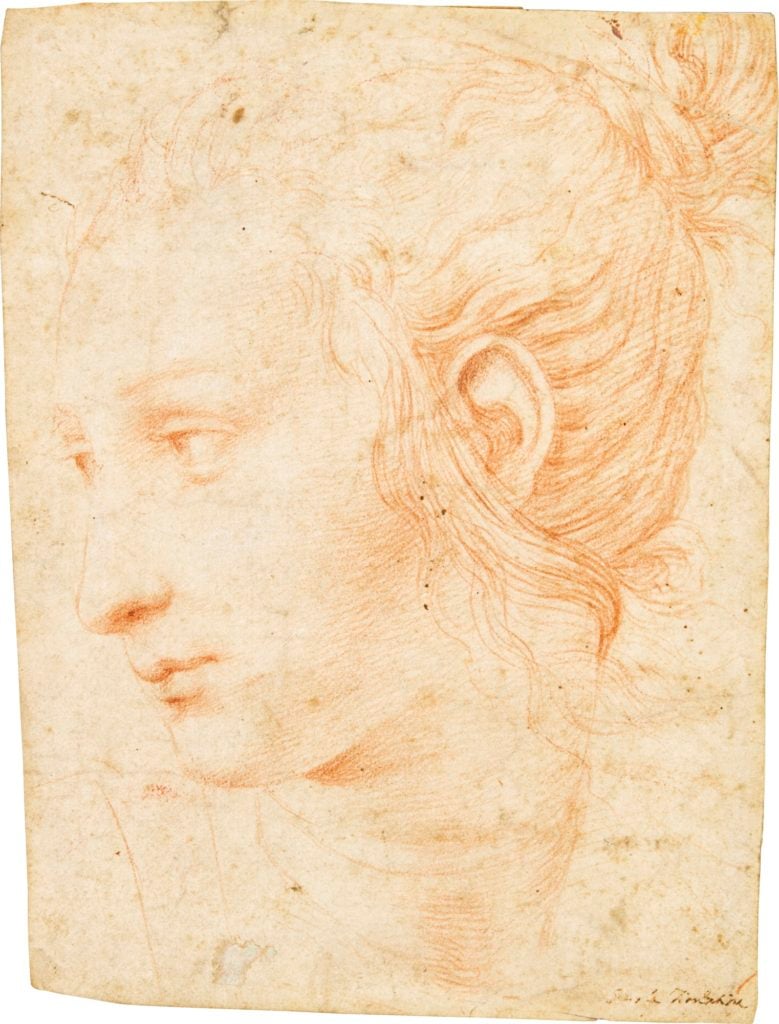

Or, in the words of Gregory Rubinstein, head of Sotheby’s department of Old Master Drawings—whose sale of Old Master and British works on paper in London on July 3 included a red chalk drawing of the head of a female muse attributed to “Circle of Raphael”—such a hazy attribution may “spur people to do some research to try to prove that it really was drawn by” the artist. (Perhaps that is the reason that the six inch-by-eight inch drawing fetched £62,500 [$78,202], well in excess of the £6,000–8,000 estimate.)

Circle of Raphael, Head of Female Muse. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Language, which is intended to clear things up, sometimes just adds confusion, and the auction world has its share of words that mean “looks like…but isn’t.” It is difficult to know how to make of all these “School of…” and “In the Manner of…” artworks that are a regular part of Old Master sales in every medium. If they cannot be fully attributed to Mr. Big Name Artist, is the work a tribute to that artist from an admirer, an exercise by an art student, or an intentional fake?

For a new buyer, these terms may all look the same. But the terminology of ignorance has its own hierarchy, as explained in both Sotheby’s and Christie’s glossary of terms. Below, we lay out the most common descriptors. With each one, we move a bit further from the time period and physical location of the artist, and prices tend to drop.

Hispano-Flemish School, The Archangel Gabriel; The Adoration of the Magi (16th century). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Since artworks with uncertain attributions are less likely to fetch high prices, auction houses are unlikely to spend valuable staff time and resources on researching them, leaving it up to department heads to look at a picture and make educated guesses. Auction staff members hope that the weave of a painted canvas might identify the country in which it was done, and certain earth tones—if visible—in the underpainting may point to a work being Italian or Dutch, but it is difficult to know which century just by looking.

Designations of some sort or another sound educated, which is better than shrugging one’s shoulders and confessing “I don’t know.” Even Sotheby’s attributed a diptych in an Old Masters sale in 2016 to a “Hispano-Flemish School,” though such a school never existed. (Fletcher acknowledged at the time that this was not an art-historical designation but a “market term,” referring to Flemish artists’ influence on Spanish art.)

A sale on July 5 at Christie’s London included a painting identified as “Follower of Giovanni Antonio Canal, il Canaletto,” which itself was followed by a lengthy description of the contents of the painting: “The Entrance of the Grand Canal, Venice, looking East, with the Doge entering the Church of Santa Maria della Salute, and the Bucintoro moored at the Riva degli Schiavoni, the Mint, the Library and the Ducal Palace beyond.” Lots of words, still meaning, “we don’t know who made this.”

Follower of Giovanni Antonio Canal, il Canaletto, The Entrance of the Grand Canal, Venice, looking East, with the Doge entering the Church of Santa Maria della Salute, and the Bucintoro moored at the Riva degli Schiavoni, the Mint, the Library and the Ducal Palace beyond. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

If an auction house claims a work is by such-and-such an artist, the prices are higher, but so are the stakes. According to lawyer Amelia K. Brankov, the legally binding conditions of sale in the back of most auction catalogues guarantee “the authorship of the work as described in bold or capitalized letters in the catalogue.” If the auction house can be proven wrong, buyers have the right to rescind their purchase within a set period of time (typically, five years). But these guarantees also often contain disclaimers relieving the auction house of liability in various circumstances, like if the catalogue states that there is disagreement among scholars about the attribution.

Buyers also have less flexibility the further they move from “By So-and-So” to the more hazy “Manner of” and “Circle of.” The term “School of” has no legal meaning at all. That term represents what one auctioneer called “a defensive gesture on the part of the auction houses,” allowing the auctioneers to generate some excitement with the association to a noted artist without having to be responsible for a claim.

Auctioneers are apt to err on the side of caution. But even that can cause problems. Back in 2006, Sotheby’s London sold a painting titled The Cardsharps, which had been labeled in the catalogue as a follower of Italian Baroque artist Caravaggio, for £42,000. It was later reattributed as a genuine Caravaggio, triggering a lawsuit. The auction house had consulted Caravaggio experts who claimed that it was a copy of another on display at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. The consignor, however, claimed that the auction house had been negligent and could have secured him a higher price with more research. In early 2015, London’s High Court decided that Sotheby’s had “reasonably come to the view that the quality of the painting was not sufficiently high to indicate that it might be by Caravaggio.”

The moral of the story: As with all transactions, it is wise for both buyer and seller to read the labels carefully—but look carefully, too.