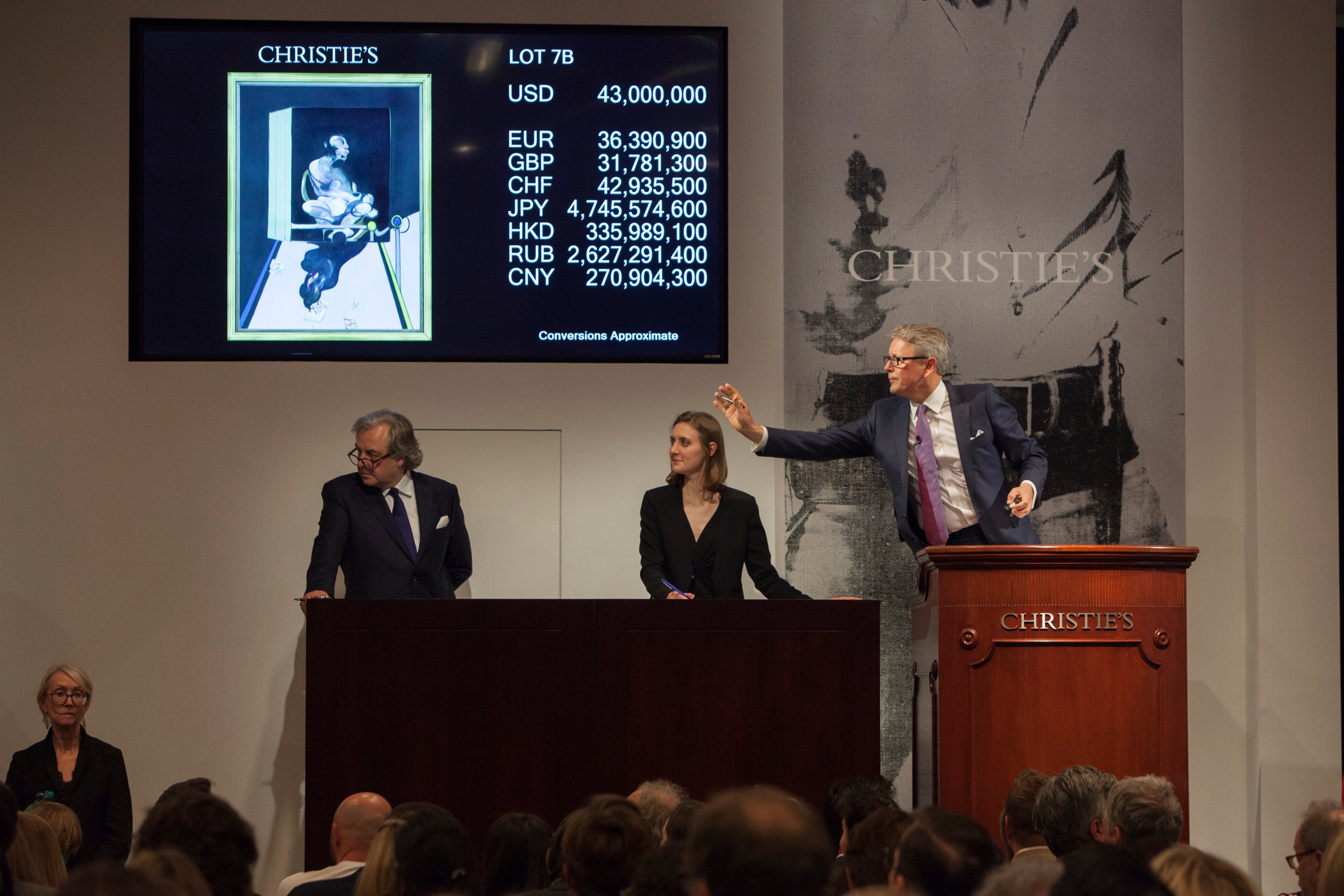

Art auctions look pretty simple, on the surface. A buyer consigns a painting, the people who want the painting bid against each other, and the highest bidder wins. That’s certainly the impression given by the auction itself, whether you attend in person or just watch online.

But it’s not the reality. At the top end of the market, art auctions are increasingly complex and opaque. Consider the three paintings Steve Wynn had up for auction at this month’s sales, carrying a combined estimate of some $135 million. One of those paintings was withdrawn after being damaged by mistake; one of them was hammered down at $33.5 million, which works out to $38 million after fees, but sold for only $37 million; and one of them was withdrawn on the grounds that it was covered by the same third-party guarantee that also included the damaged work.

If you don’t entirely understand what’s going on in the previous paragraph, then you’re exactly where Christie’s and the art world more generally want you to be. The art market is built on opacity, and the less that people know about what’s going on, the more opportunities there are for profit and arbitrage. When you take a closer look at this season’s big auction sales, one trend seems to be emerging: Auctions are looking less and less like anonymized price-discovery mechanisms and more and more like gussied-up private sales.

Often, the consignor ends up selling to an art dealer or speculator, after losing their bet that they’d be able to smoke out a competing art buyer who for whatever reason wasn’t willing or able to bid at the auction.

A good amount of this auction activity can be deciphered, and some of it is relatively easy to understand. If Christie’s damages a painting, then it makes sense that they would withdraw it from auction. But what happened to Wynn’s other two paintings? One of them, Double Elvis [Ferus Type] (1963) by Andy Warhol, received a series of bids. After an underbidder put in a bid of $33 million, the work was finally hammered down to the high bidder for $33.5 million.

Andy Warhol’s Double Elvis [Ferus Type] (1963). Image courtesy of Christie’s.

That figure—that is, the hammer price plus the premium—is the price reported by Christie’s and the press: It is, after all, the total amount that the buyer pays. (There’s also sales tax, which isn’t reported, since most buyers avoid it by shipping the works they purchase out of state.)

But that’s not the final price listed by Christie’s on its website, because the bidding didn’t stop at $33 million.

The final purchaser bid $33.5 million, or $500,000 more than the underbidder. According to the preset formula, that means the winning bidder would ordinarily pay a total purchase price of $38 million.

An auction is meant to be a level playing field. You bid more, you pay more. Except, in this instance, the buyer didn’t pay $38 million: According to Christie’s, she (or, more likely, he) paid just $37 million. It’s a nice trick if you can get away with it: bid more, pay less. The final reported price for the Warhol is at least $437,500 lower than someone else was willing to pay on the day of auction, which is not generally how auctions are supposed to work.

A Side Deal

The reason why the final bidder managed to get a $1 million discount is a side deal that she had made with Christie’s. Christie’s had guaranteed Wynn a certain amount for the painting, in order to persuade him to consign the piece in the first place. That created risk for the auction house: If it couldn’t sell the painting, it risked ending up out $30 million or so, with nothing to show for it but a painting that had just been “burned” at auction. (Failure to sell at auction is the art-world equivalent of a scarlet letter, and the work becomes much more difficult to sell.)

In order to avoid that outcome, Christie’s found a bidder willing to guarantee the work by placing something known as an “irrevocable bid” before the sale began. Even if no one else bid on the painting, that irrevocable bid would always be there, which meant that Christie’s knew that the painting was guaranteed to sell.

Why would a bidder show their hand to Christie’s by entering an irrevocable bid weeks before the auction? What’s in it for them? The answer, simply, is money. In return for receiving the irrevocable bid, Christie’s promised to share with the bidder some of its profits on the painting—some of the buyer’s premium payable over and above a certain amount.

Specifically, if the guarantor ended up winning the work, Christie’s would pay her a $1 million “financing fee.” Although that figure isn’t public, it’s easy enough to determine: The guarantor bid $33.5 million, which would typically result in a final price, including premium, of $38 million. After the rebate of the financing fee, however, the final price is actually listed as $37 million.

The guarantor outbid the person willing to pay $37.44 million, and managed to walk away with a $37 million painting.

To be sure, there are other ways of looking at this transaction. You can say that the bidder paid $38 million for the painting and that the guarantee was a separate transaction, or you can say that the bidder still ended up paying roughly $38 million more than she would have netted if she’d just let the underbidder win. Both are true. But the official final price is unambiguously $37 million, and going forwards, everybody is going to consider this to be a $37 million painting, not a $38 million painting.

A Rigged System?

From the point of view of everybody else at the auction, such agreements might make the whole system seem rigged in one person’s favor. Why bid on a guaranteed work when the playing field isn’t level and someone else can outbid you while still paying less? After all, while the existence of the guarantee is revealed by the presence of º ♦ hieroglyphics in the auction catalogue (but not on the website, annoyingly), the identity of the guarantor is a closely-held secret, as is the amount of money that has been guaranteed to the seller. Only one bidder knows those two crucial data points, and that knowledge is extremely valuable.

Pablo Picasso, Fillette à la corbeille fleurie (1905). Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd.

In such a context, bidding on the work becomes less attractive: It’s irrational to get into a fight where your opponent has you informationally and financially outgunned. And so while third-party guarantees are good for minimizing the auction house’s downside risk, they also depress the amount of bidding from everybody else.

The results can be seen in the two most expensive paintings sold at auction this season: Modigliani’s Nu couche (sur le cote gauche) (1917), which sold at Sotheby’s for $157.2 million, and Picasso’s Fillette à la corbeille fleurie (1905), which sold for $115.1 million. Both of them ended up selling to their respective guarantors; there were no other bids.

When that happens, the consignor can be forgiven for wondering whether it was really worth sending the piece to auction at all. The Modigliani hammered for $139 million, which means that Sotheby’s and the guarantor, between them, split a buyer’s premium of more than $18 million. Even if the seller negotiated an “enhanced hammer” and received more than hammer price, it’s fair to assume that he ended up paying Sotheby’s well over $10 million to sell the work, and that the painting was essentially pre-sold, to the final buyer, at the final price, long before any bidders entered the auction room.

Sotheby’s has a private-sales department which specializes in connecting buyers and sellers, and that department could surely have done the same deal, for a substantially lower fee. (The auction house did not reply to a request for comment.) Although commission fees for private sales are not made public—in part because they are negotiable—the head of Christie’s private sales has previously stated that they are “often lower and never higher than auction fees.”

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917). Courtesy Sotheby’s.

Auction houses have a fiduciary responsibility to the sellers of works, but at some point the interests of the two parties are not entirely aligned. A world where paintings regularly and predictably end up selling to their guarantors is a world where if you can get a guarantee for $X, then you can just as easily sell the work privately for the same amount, without the rigamarole, extra costs, and extra fees involved in taking it to auction. The seller loses out on potential upside, in the event of an auction-room bidding war, but gains in terms of lower commissions paid to intermediaries.

At the same time, it’s clear where the auction houses want trophy art to appear. Auction sales have been very strong for the past few years, while the houses’ private-sales departments peaked in 2013–14 and show no signs of returning to those levels.

What seems to be happening, then, is that guarantees are the new private sales. Except the big difference is that the world of guarantees is mostly a world of professional art dealers, with the occasional semi-pro making an appearance.

Why Get a Guarantee?

In theory, it makes sense for a devoted art lover, who really wants to buy a certain work of art, to enter an irrevocable bid before the auction starts. She’s not going to change her mind about bidding on the work, and in the event that she does end up getting outbid, at least she’ll be compensated for her troubles. In practice, however, third-party guarantees nearly always come from professional or semi-professional art dealers who sell art just as frequently as they buy it, and who treat third-party guarantees more as a profit opportunity than as a way to buy long-coveted paintings.

If these are the people increasingly ending up buying major works at auction, then at some level that defeats the purpose of hiring an auction house in the first place. You might as well just sell directly to the dealer-guarantor. Auction houses have a unique ability to be able to reach a large number of deep-pocketed art collectors, but anybody with a $115 million Picasso or $155 million Modigliani knows exactly who the big-name dealers are in that space, and is more than capable of getting in touch with them directly.

In a sense, then, the real purpose of going to auction is increasingly just rip-off insurance. You could sell your Picasso directly to a dealer for $115 million, but how do you know the dealer isn’t lowballing you? Answer: by making that dealer buy it at auction, via a third-party guarantee. If the real value of the painting is much higher than $115 million, then someone is very likely to pop up in the auction and pay more. If it isn’t, then the dealer will go home with the work.

On the other hand, that doesn’t explain why a self-proclaimed art dealership would consign works to auction. Steve Wynn’s works were ostensibly being sold by Sierra Fine Art LLC, a company which purports to be a high-end online art gallery, but whose website is laughably amateurish. If Wynn is serious about being a dealer, he shouldn’t need to rely on Christie’s to ratify the value of his inventory.

Screenshot of Double Elvis, Le Marin, and Femme assise au chat on the Sierra Fine Art LLC website.

And there’s mystery, too, surrounding the third Wynn painting, Picasso’s Femme au chat assise dans un fauteuil (1964). That painting was not damaged, but was withdrawn at the same time that the damaged work was withdrawn, on the grounds, per Bloomberg, that “the two were covered by the same third-party guarantee.”

How does a third-party guarantee of two separate paintings work? Maybe it’s just two different irrevocable bids, offered on the basis that the guarantor will only guarantee one of the paintings if she can also guarantee the other as well; maybe it’s more complicated than that. Again, the details are, as ever, kept highly confidential. (A spokeswoman for Christie’s says the auction house does not comment on the details of financial arrangements with its clients.)

In any event, the result was that Wynn wasn’t able to sell his undamaged Picasso, just because he wasn’t able to sell his damaged one. There’s surely a good reason for that, but almost no one really understands what it is, and those who know aren’t telling. Which tells you pretty much everything you need to know about the true transparency of today’s auction market.