Market

A Three-Story Mural Keith Haring Created for a Catholic Youth Center Sold for $3.9 Million—to the Chagrin of the Artist’s Foundation

The 85-foot mural was taken down from the walls where Haring painted it in the early 1980s.

The 85-foot mural was taken down from the walls where Haring painted it in the early 1980s.

Caroline Goldstein

A 85-foot-wide mural that Keith Haring created on the wall of a Catholic youth center on Manhattan’s Upper West Side was meticulously removed and then sold off at Bonhams on Wednesday night for $3.9 million with fees. The result is comfortably within the presale estimate of $3 million to $5 million—but not everyone is thrilled by the result.

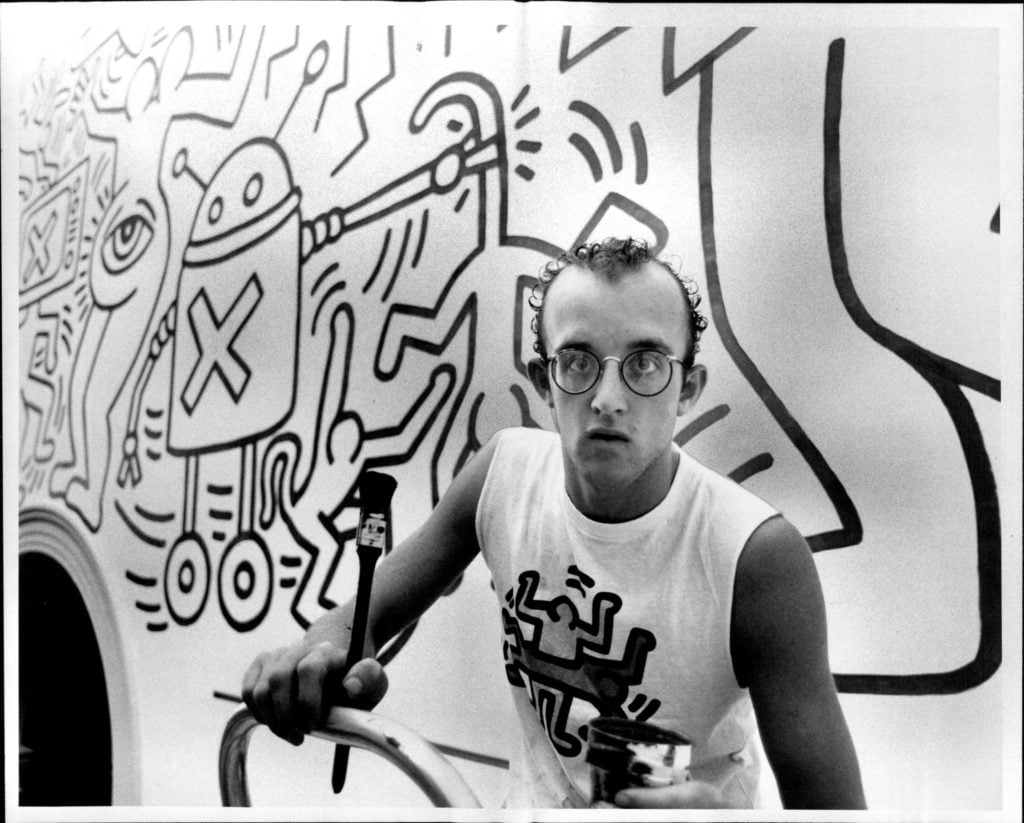

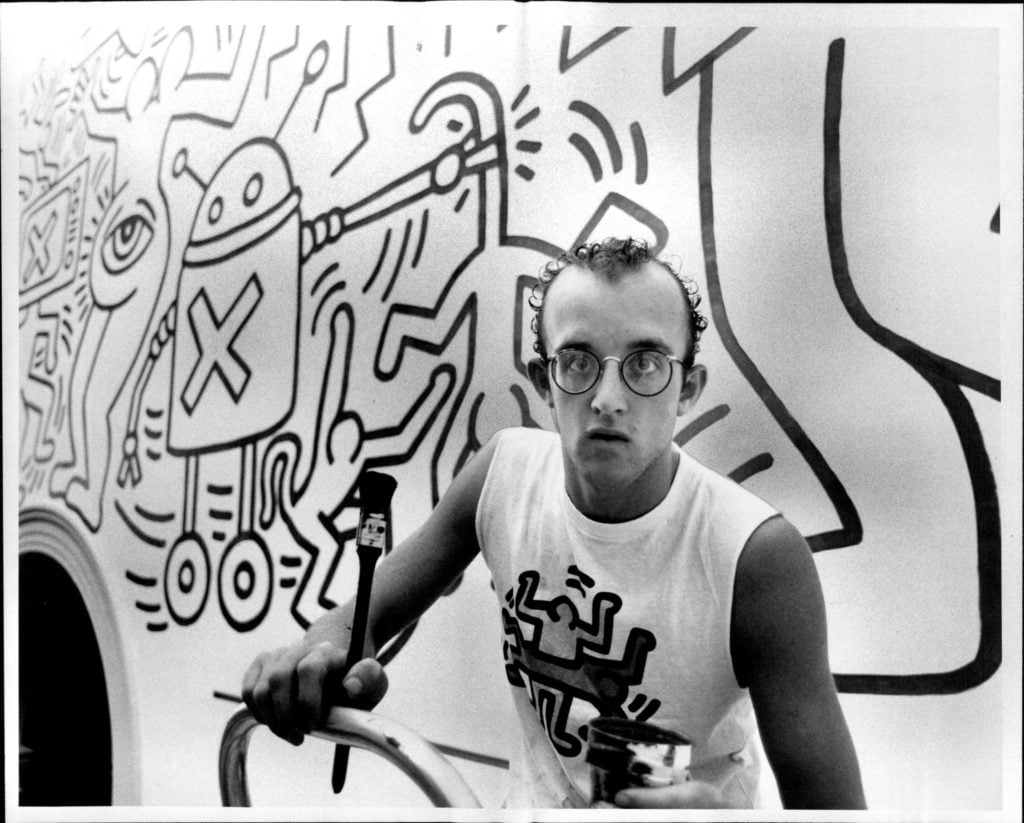

During his short but prolific career, Haring painted murals around the world, from Chicago to Antwerp, often adorning the walls of other youth centers and elementary schools and bringing in local children to help paint them. But these monumental, site-specific works have never ended up on the auction block—until now.

The Grace House mural had an unusual trajectory. Haring was persuaded to create it by members of the youth center, including a teenager named Benny Soto who befriended the artist at a nearby nightclub they both frequented. (Soto would go on to serve as Haring’s studio assistant until the artist’s death at 31 years old from AIDS-related complications.)

Soto and his friend David Almodovar eventually convinced the director of Grace House to let Haring come make his mark on the center. One evening in either 1983 or 1984—no one can agree which—Haring got to work. Over the course of a short 40 minutes, Haring painted 15 figures that spanned his “visual lexicon” snaking around the three-story staircase, interrupted only by a fire extinguisher panel.

Parts of Keith Haring’s mural at Grace House. Courtesy of Bonhams.

Haring rendered his now-iconic silhouettes of dancing, flailing, and jiving figures (as well as a few dogs) in thick black lines without any preparatory sketch or outline, some still retaining the drip marks from the paint.

The mural remained at Grace House well after the center itself eventually shut down. But more recently, the cost of retaining the building became too steep for the Ascension Church next door—which owned the building and had leased the space to Grace House—to manage.

As the church prepared to sell the building, it spent $900,000 to excavate and conserve the mural with the help of the firm EverGreene Architectural Arts. The firm managed to retain all of the figures by cutting them, piece by piece, off the wall. Then, the church consigned the work to Bonhams, where it was sold on Wednesday as a single lot. The proceeds, according to the auction house, will be put toward capital improvements in the church’s parish.

Parts of Keith Haring’s mural at Grace House. Courtesy of Bonhams.

Haring’s eponymous foundation, meanwhile, was not particularly thrilled by this turn of events. “We are disappointed,” Gil Vazquez, the president of the Keith Haring Foundation, told the New York Times last month. “This mural was not meant to be owned by a collector. It was meant to brighten a room full of children.”

Vazquez said he hoped the work would return to public view and that the church might donate a portion of the sale’s proceeds back to the artist’s foundation or to a cause he supported. A representative for Bonhams said the work sold to an anonymous buyer over the phone and that she believed a portion of the proceeds would be donated, but did “not have further details.”

That may not end up happening, however. Vazquez told Artnet News that he learned at a panel discussion at Bonhams last week that the Ascension Parish was in $3.5 million debt to the Archdiocese of New York, so “the $3.8 million that [the Haring mural] sold for does not cover their debt and would make it less likely that they would be able to keep that commitment.” The church did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Vazquez added that he hoped the work “can be displayed and enjoyed by the public in some fashion and that it remain together as one work. We are well aware that there are no guarantees that either of these things will happen.”