New York’s oldest museum had a tough pandemic year. The New-York Historical Society, founded in 1804, was shuttered for months and has been operating at 25 percent capacity since September. As revenue fell 30 percent, it laid off 15 percent of its staff and furloughed 11 percent more.

With financial pressures showing no sign of letting up, the institution decided to take a drastic step: sell an iconic Childe Hassam painting from its collection.

Estimated at $12 million to $18 million, Hassam’s Flags on 57th Street, Winter 1918 (1918) will be offered at Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern art evening sale on May 12 alongside gems by Monet and Cézanne. The work is poised to set a new high for the American Impressionist, whose record hasn’t been challenged in more than two decades.

The New-York Historical Society is the latest institution to sell art amid snowballing fallout from the pandemic. This season, it’s joining six other museums (the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, the Art Institute of Chicago, the San Diego Museum of Art, the Newark Museum of Art, and the Brooklyn Museum), most of which are taking advantage of temporarily loosened deaccessioning regulations. Notably, the majority of the works on offer are in the American art category, a sector that has seen mostly lackluster sales since the financial crisis.

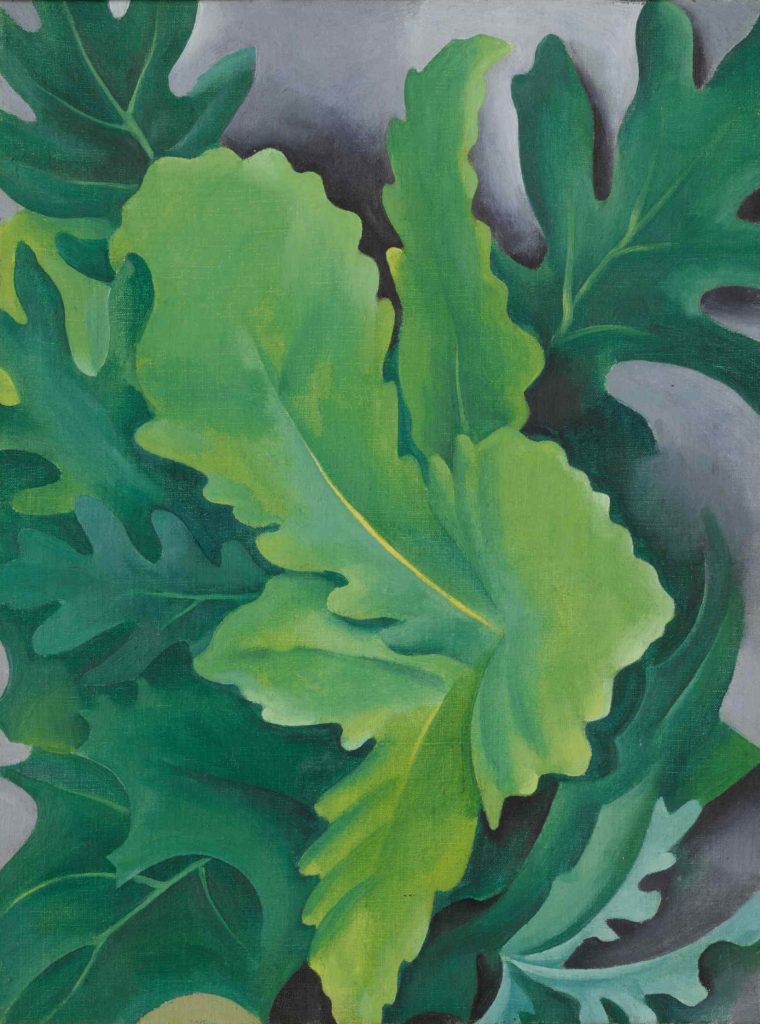

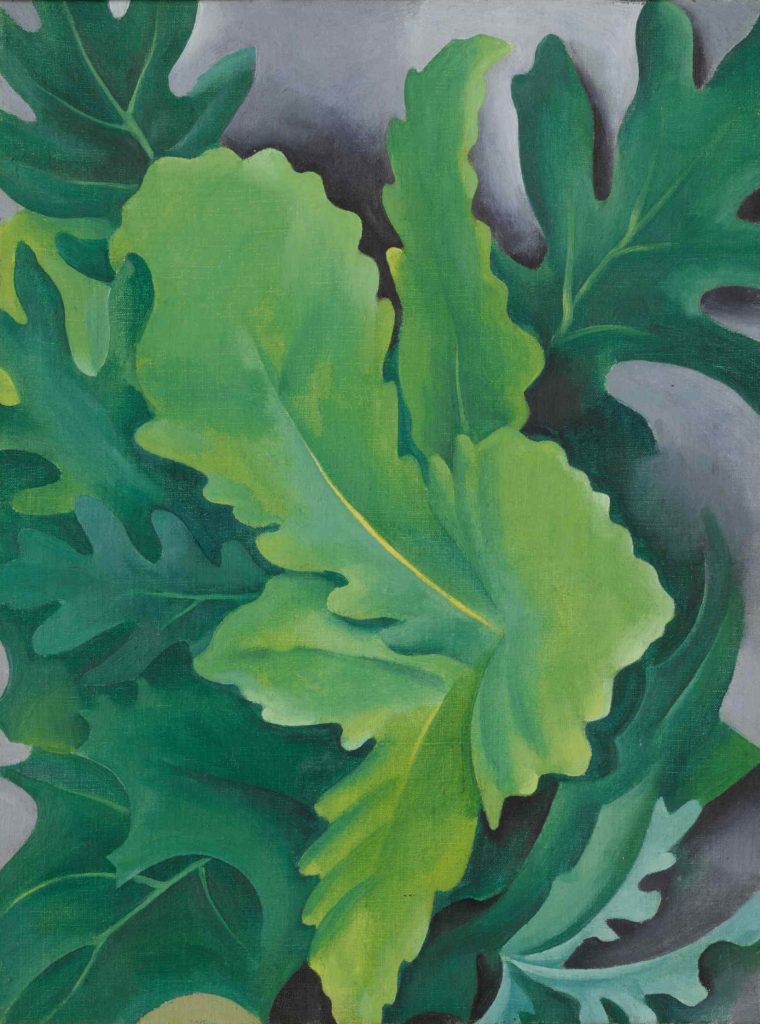

Georgia O’Keeffe, Green Oak Leaves (ca. 1923), from the Newark Museum of Art. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The works arrive on the auction block halfway into a two-year window during which museums have been granted leeway to use the proceeds from art sales for “direct collection care,” an umbrella term that covers everything from curators’ salaries to HVAC systems. (Traditionally, funds from art sales can only be used to acquire more art.) Tens of millions of dollars’ worth of art has already been sold under these relaxed rules, which are set to expire on April 10, 2022.

Nina Del Rio, head of advisory and museum services at Sotheby’s (which is offering the entire slate of museum works this season), is seeing “a steady flow” of museum consignments in the pipeline. “Some conversations are happening and others haven’t started yet,” she told Artnet News.

More Museums Mulling Art Sales

When the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which had a $150 million revenue shortfall last year, recently floated the idea of selling art, the blowback was swift and fierce. The institution is still considering whether to apply sale proceeds to collection care, but hasn’t determined what will be sold and how, according to a spokesman.

The Whitney Museum of American Art, which rarely sells works from its 25,000-piece collection, may also join the fray after completing a three-year strategic review of its holdings, according to director Adam Weinberg.

“I am open to the idea,” Weinberg said in a recent interview with art-industry insider Josh Baer of using funds from art sales for collection care. Of the 3,000 artists in the Whitney’s permanent collection, two-thirds are living, and their works are off-limits for deaccessioning, Weinberg said. A Whitney spokeswoman declined to comment further.

While deaccessioning is usually a standard part of collection management for museums, the temporary policies have ignited fiery debate.

Marsden Hartley, Shell, from the Newark Museum of Art. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Last fall, the Baltimore Museum of Art withdrew multimillion-dollar works from Sotheby’s after an outcry by former trustees and other museum professionals. The Everson Museum of Art was also criticized for selling its only Jackson Pollock painting and eyebrows were raised when the Brooklyn Museum sold its sole Cranach.

“It’s going to be complicated for a long time,” said art lawyer Nicholas O’Donnell, who argued against the Berkshire Museum’s plan to deaccession in 2017. (The legal battle went all the way up to the Massachusetts supreme court; ultimately, the museum was allowed to sell art to close a financial gap, netting $53 million.)

“The opposition is not as monolithic and singular as it used to be,” O’Donnell said. “There are people who would say it’s OK to sell art to emphasize some part of the programming. And there are people who would say it’s OK to sell art for whatever reason they want.”

Looking for Duplicates

Museums, perhaps having internalized some of the blowback, are opting this season to sell works that they say replicate others in their collection.

The New-York Historical Society owns two flag paintings by Hassam. The one it is selling, Flags on 57th Street, Winter 1918, was a bequest from collector Julia Engel in 1984. It is keeping The Fourth of July, 1916 (The Greatest Display of the American Flag Ever Seen in New York, Climax of the Preparedness Parade in May), gifted by the late financier Richard Gilder in 2016.

The Brooklyn Museum is parting with Mary Cassatt’s Baby Charles Looking Over His Mother’s Shoulder (ca. 1901), one of 17 pieces by the artist in its collection. Estimated at $1 million to $1.5 million, it will be offered in Sotheby’s American art sales.

Mary Cassatt, Baby Charles Looking Over His Mother’s Shoulder No. 3 (ca. 1901), from the Brooklyn Museum. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The work has been rarely shown and was considered for deaccession “for some time,” according to a spokeswoman. Its “departure would in no way undermine the strength of our collection or our ability to continue to tell the story of Cassatt and women’s transformative role in the 19th century avant-garde,” she said.

The Newark Museum of Art is selling off 20 objects from its 130,000-piece collection following a strategic review. It plans to use the proceeds for collection care. Georgia O’Keeffe’s Green Oak Leaves, slated for sale, is one of its four paintings by the American modernist. The museum is also selling two of its seven Hassam works, including Woman Cutting Roses in a Garden (1889), estimated at $1 million to $1.5 million.

A Moment for Hassam

Museums typically hold onto the best examples by an artist, but buyers are still attracted to the institutional provenance, prestige, and freshness of deaccessioned works. Experts say the museum trove at Sotheby’s could reenergize the American art market.

The sector, which covers a roughly two-century period from colonial-era portraits by Gilbert Stuart through American modernism, “changed in 2008 and it never really recovered,” said Elizabeth von Habsburg, managing director of Winston Art Group. Hassam and Cassatt have been “volatile” at auction while O’Keeffe’s market is strong in Asia, she added.

Hassam’s flag paintings are in a category all their own. Most works in the series of 30—considered his most famous (and expensive)—are owned by museums. One hangs next to President Joe Biden’s desk in the Oval Office.

Hassam’s auction record was set in 1998 for Flags, Afternoon on the Avenue (1917), which fetched $7.9 million.

The series was inspired by a “Preparedness Parade” on Fifth Avenue in 1916, which celebrated the end of America’s isolationist policies as it prepared to enter World War I.

Childe Hassam, Piazza di Spagna (1857), from the Newark Museum of Art. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Like most works in the series, Flags on 57th Street, Winter 1918 depicts a busy urban landscape but here shown from a unique bird’s-eye perspective. Three flags wave in the wind; snow covers the ground.

The New-York Historical Society declined to comment on the value of the painting or discuss its valuation process. It hasn’t deaccessioned art in 20 years, a spokesperson said.

If sold within the estimated range—$12 million to $18 million—the proceeds would amount to a windfall. To put things in perspective, the museum’s total revenue was $42.7 million during the 2018–19 fiscal year, according to its last available tax return.

And herein lies the danger for museums, O’Donnell said.

“If you view the collection as a revenue source, will you keep managing a nonprofit institution as carefully as you should?” he said. “If, in the back of your mind, you know that if things don’t work out, you can make up the difference here and there by selling a painting?”