Galleries

Are Hermann Nitsch’s Actionist Paintings the Answer to Zombie Formalism?

Inside the controversial Vienna Actionist's New York painting show.

Inside the controversial Vienna Actionist's New York painting show.

Cait Munro

Despite the fact that he’s been making art for almost six decades, has three museums dedicated to his work, and is an influence on scores of younger artists, Hermann Nitsch is not a household name—at least, not in the United States. But gallerist Marc Straus would like to change that.

Housed on an unassuming block on the edge of Chinatown, Straus’s spacious two-story New York gallery currently hosts a series of paintings that document the ritualistic, Dionysian performances that have come to define Nitsch’s storied career.

At 77, the former Vienna Actionist has staged more than 100 performances, most notably the Orgien Mysterien Theater, which is described by the artist in a 2014 statement as “a cult existential festival celebrating life.” The performances typically involve religious sacrifices, mock crucifixion, animal blood, entrails, robes, fruit, dance, and nudity.

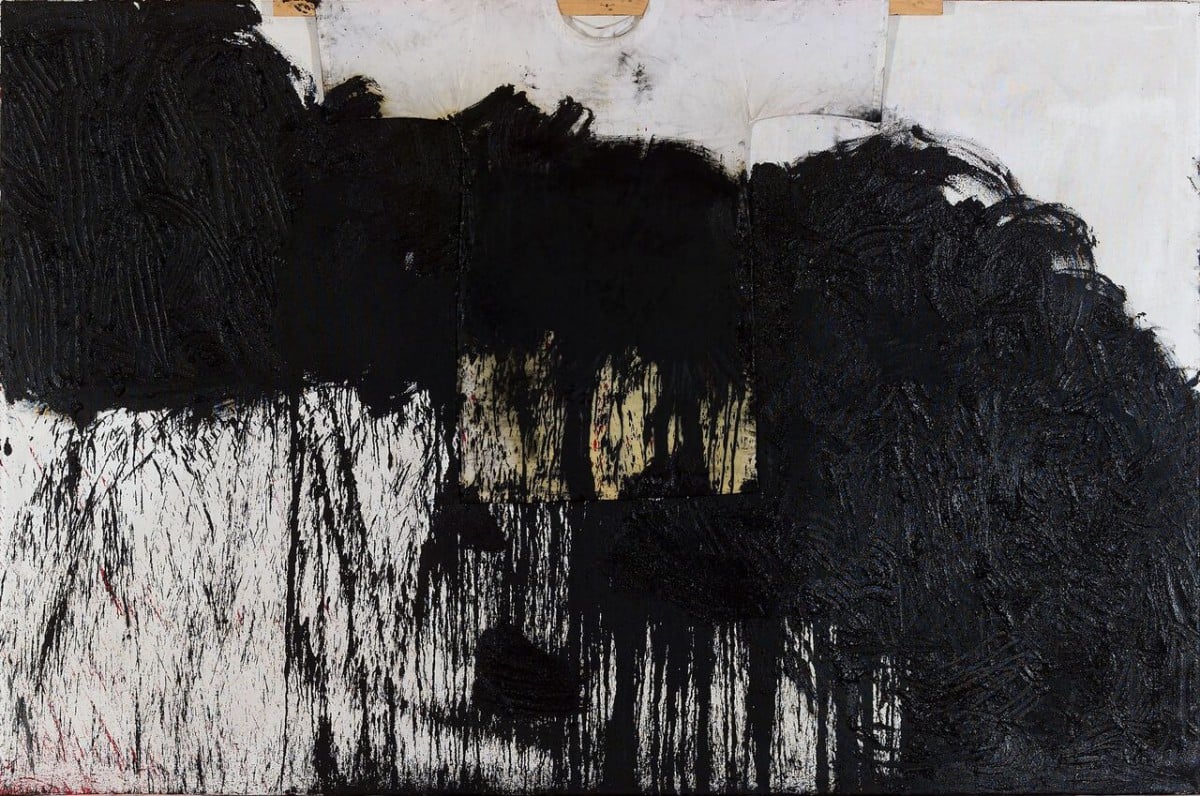

Hermann Nitsch, Schuttbild (2010).

Photo: Courtesy Marc Straus Gallery.

Nitsch’s paintings, which are rendered in a palette of blacks, browns, and reds, function as the documentation of these events, much the way photography and sets of instructions documented many of the New York “happenings.” Interestingly, Allan Kaprow coined the term “happening” in 1957, the same year that Nitsch staged his first Orgien Mysterien Theater performance. While the two movements bear common threads, Nitsch and the Vienna Actionists made art that was much more aggressive in nature than that of the peace-loving activists in New York.

The sweeping gestures, hand prints, footprints, and smears of animal blood on Nitsch’s canvases feel like intense communiques from people on a mission to discover the untold secrets of their own humanity.

On September 8, the gallery hosted a private opening attended mostly by friends of Nitsch and his wife Rita, as well as writers, curators, and artists such as Rirkrit Tiravanija, who seemed genuinely starstruck by Nitsch’s presence. The evening included a panel discussion by three scholars of Nitsch’s work: art critic, historian, and Brooklyn Rail contributor Robert C. Morgan; critic, writer, and editor Paul Laster; and writer, editor, and Pratt Institute professor Jonathan Goodman.

The trio—with a few pointed interjections by Nitsch—discussed the importance of the artist’s gritty, transgressive, corporeal oeuvre, especially considering the glossy landscape of America’s contemporary art scene. At times, the trio seemed to offer him up as the solution to the problem of zombie formalism.

Nitsch painting during a performance in 2009.

Photo: Daniel Feyerl.

Goodman admitted that when he first saw Nitsch’s work, he didn’t quite know what to make of it. “One of the things I was struck by is that these paintings are in a way the expression of content—just the spilling of guts, the spilling of red paint, the spilling of black paint…they are remarkably improvised, but at the same time there is some control over them.”

While only two of the canvases at the gallery contain animal blood (the rest are rendered in acrylic paint), Nitsch’s use of the medium has proven both essential and controversial throughout his career. Earlier this year, the Museo Jumex in Mexico City pulled the plug on a planned exhibition of Nitsch’s work after animal rights activists started an online petition that garnered over 5,000 signatures. The exhibition was instead shown in Sicily at the Cantieri Culturali alla Zisa.

Despite fervent claims that his work is cruel to animals, Nitsch insists that he loves our four-legged friends, further noting that the carcasses he uses in his performances come from his butcher. While the artist still employs animal blood and carcasses in his works, the last time one of Nitsch’s performances featured a real slaughter was 1998.

A photograph from a 2013 performance.

Photo: Courtesy Marc Straus Gallery.

The artist has said that he was “very, very sad” about the closure of the show, but it certainly isn’t the first time he has faced adversity to his work. Nitsch has been imprisoned three times in his native Austria (where he still resides), causing him to briefly move to Germany, where his avant-garde works were generally tolerated.

Despite the social, political, and religious implications of the performances, Nitsch insists that he is deeply apolitical. He also rejects any desire by the viewer to mine for symbols in the various components of his work, perhaps unwittingly echoing Gertrude Stein’s “a rose is a rose is a rose” modernist sentiment. “It is what it is,” he states. “People want to find symbols…[but] for me, a shape is a shape.” When asked about the meaning of the paint-splattered white robes that adorn several of his canvases, he simply states: “They are what I wear when I am working.”

This provides a stark contrast to other artists that have worked with blood and bodily artifacts, who often employ the medium specifically for its symbolic qualities. Artists such as Ana Mendieta, Carolee Schneemann, Judy Chicago, and others in feminist art circles have employed menstrual blood to celebrate womanhood and rid the substance of its taboo, while “shock” artists such as Andres Serrano, Dash Snow, Terence Koh, and Piero Manzoni have used urine, feces, and semen as a statement-making element of an artwork.

But Nitsch vehemently rejects the urge to politicize his work. Through his performances, he attempts to connect people with their most basic human urges and emotions, and through his paintings he documents these connections.

“One of the things I was struck by, watching a video of one of his recent performances is how…there was this tremendous sense of being in the moment and existing in what is essentially a spiritual relationship to the medium that went beyond spirituality into what I would say was almost a pious, religious state,” says Morgan.

Hermann-Nitsch,-Schuttbild (2013).

Photo: Courtesy Marc Straus Gallery.

Nitsch’s relative lack of celebrity in American art circles may be because of our fear of art that is confrontational, not just on a visceral level, but on this deeper, more psychologically probing one. Just as viewers are initially determined to search for symbolism and political statements in Nitsch’s work, he is determined to confront them with their own humanity, and that makes people uneasy.

“I was uncomfortable with it not because Nitsch was wrong, but because I was wrong,” Goodman says of his initial introduction to Nitsch’s work. “We have to allow for the fact that this is a ritual, almost religious refastening of primal emotions that are not going to go away because of our unconscious. These basic emotions are so powerful that we have to acknowledge them.”

“Hermann Nitsch” is on display at Marc Straus Gallery from September 9–October 18, 2015.

Related stories:

Sicily Welcomes Hermann Nitsch’s Cancelled (and Controversial) Museo Jumex Show

2015 Fall Art Preview: The 28 New York Exhibitions Everyone Should See

Roy Lichtenstein’s Destroyed Mural Briefly Resurrected at Gagosian