The Art Detective

High-Flying Charity Auctions Help the Causes the Art World Supports. But Who Do They Actually Benefit?

For artists, at least, charity auctions can be a chance for their markets to soar—or fly too high to the sun.

For artists, at least, charity auctions can be a chance for their markets to soar—or fly too high to the sun.

Katya Kazakina

It was a high-wattage night at the Norton Museum of Art in Palm Beach on February 3, with a live auction by Sotheby’s, billionaire attendees like Julia Koch and John Paulson, and such celebrities as polo player “Nacho” Figueras, race car driver Jimmie Johnson, and Victoria Secret model Lorena Rae. The 800 tickets sold out in a blink, with prices ranging from $1,500 for individuals to $100,000 for sponsors.

By the time the dust settled, the Norton had raised $3.8 million for its curatorial, educational, and community-engagement programs. It was so much fun some guests forgot to eat.

“A lot of times at these galas you sit, it’s quiet, you have your rubber chicken,” said Sue Hostetler Wrigley, a Norton trustee. “This was not. This was the next level.”

Much of the event’s electricity resulted from the presence of 20 artists from as far afield as the Netherlands and Brazil. The six lots of the live auction totaled more than $700,000. One of the star artworks was an abstract painting by Marina Perez Simão that fetched $140,000 (her primary market prices range from $35,000 to $250,000). A painting depicting two nudes by George Rouy went for $160,000 (his primary prices top at $100,000).

The results are noteworthy—and not just because they blew past the presale estimates. Both artists are represented by blue-chip galleries: Perez Simão is at Pace, Rouy at Almine Rech. There are waiting lists for their primary market works. Not a single piece by either artist has appeared at auction, according to the Artnet Price Database.

“I gotta call my mom,” London-based Rouy could be overheard saying excitedly after the gavel fell.

Artist Marina Perez Simão, right, with Eva Al-Thani and Ambassador Sheikh Meshal bin Hamad Al-Thani at the Norton Museum of Art gala. Photo by Carrie Bradburn for Capehart.

Charity auctions have long been places to find deals and steals—and potentially write off some of the purchase cost (more on that later). In addition to helping the institutions we love and causes we support, these glamorous fundraisers are also a breeding ground for future market stars. They create a virtuous cycle—not dissimilar to the curse of BOGO—where everyone seems to benefit, but which is based on the asymmetry of access and information. While galleries and artists don’t directly profit from these sales, many find ways to indirectly monetize them to build up publicity and justify steep primary market prices.

But there’s also a risk. Many moons ago, a painting by Jacob Kassay, estimated at $2,000 to $8,000, fetched $94,000 at a Kitchen benefit in New York, unleashing a speculative craze for the silvery, shimmering paintings and leading to the young artist achieving an auction record of $317,000 at dizzying speed. Then prices fell off the cliff.

That number—so shocking at the time—looks almost quaint now, a decade later, when new works by untested artists like Anna Weyant sell for more than a million dollars at auction. Which is precisely the point. Emerging art is a high-stakes game. Those who can afford to play may get access to coveted works by artists too hot to obtain through galleries, which prioritize institutions over mere mortals, no matter how rich.

In this dynamic, artists who offer up fresh work for a charity auction know it can reap big rewards for the cause in question—while also potentially throwing their market out of whack. It’s a risk that buzzy artists are frequently enjoined to undertake.

Nicole Wittenberg Sunset 36 (2023) is slated for amfAR’s charity auction in Palm Beach on March 11. Courtesy of the artist; the Journal Gallery, New York; and Acquavella Galleries, New York and Palm Beach.

“The ask is constant on any big artist these days,” said Michael Nevin, owner of the Journal Gallery in New York. “It’s pretty tricky to get top works from top artists.”

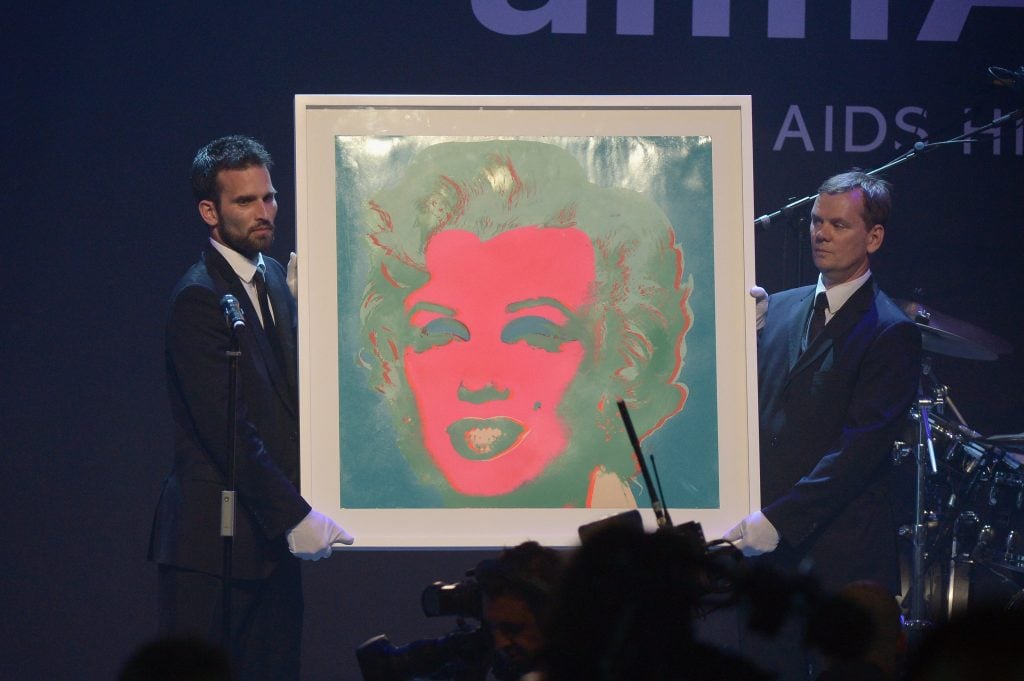

Nevin would know. As the curator of amfAR’s auctions, he goes hunting for art donations all the time. He’s good at it. The nonprofit’s upcoming gala in Palm Beach on March 11 will include a brand new work on paper by George Condo, which would be priced at $750,000 on the primary market, and a sunset painting by Nicole Wittenberg, that typically retails for $42,000.

“A lot of artists give to give,” Nevin said. Some, like Eddie Martinez, are just generous, he said. Others, like Kenny Scharf, lost friends during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and want to support amfAR, which has raised millions of dollars for AIDS research. There are countless others.

Museums often tap artists they have championed—and these artists often step up. In 2013, Jasper Johns created a work specifically for New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art to auction in order to raise money for its new building. It fetched $2.85 million, part of a group of other works benefiting the Whitney that Sotheby’s included in its marquee May sales of contemporary art that year. Altogether, the group totaled $19.1 million—eclipsing the estimate of $8.8 million to $12 million.

Auctioneer Robert Woolley, left, at Gay Games Auction in 2001. Photo: Liz Hafalia/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images.

That sale was a turning point for charity auctions, according to Nina del Rio, Sotheby’s head of advisory and museum services. Up until then, charitable auctions were separate events. The New York Times obituary of Sotheby’s auctioneer Robert Wooley, who died in 1996, described him as “witty and tart-tongued pitchman who wheedled, needled, cajoled and shamed his society friends into spending millions of dollars at charity auctions.” In 2008, the Red auction, championed by Bono and Damien Hirst, made headlines, raising $42 million for AIDS research.

But the Whitney sale’s collaborative approach—incorporating the charitable works into a blue-chip evening auction—changed the game, and its success led to more collaborations, including with the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 2015 and the Hammer in 2019. All surpassed their high estimates.

“You got a couple of drivers,” del Rio said about the success of this approach. “You are celebrating an institution and you are giving buyers access to this great primary-market material.”

Works solicited by Thelma Golden to raise money for the new home of the Studio Museum in Harlem set off a feeding frenzy at the start of Sotheby’s contemporary art evening sale in May 2018. Mark Bradford, who has credited Golden with his career takeoff, created a painting, Speak, Birdman, for the sale. Estimated at $2 million to $3 million, it soared to $6.8 million. A painting by then relative newcomer Njideka Akunyili Crosby fetched $3.4 million.

A street-level view of the forthcoming Studio Museum in Harlem. Courtesy Adjaye Associates.

The Studio Museum group raised $20.2 million, obliterating the estimated range of $6.8 million to $9.9 million. It was a perfect storm for the market, which was just starting to revalue the contribution of Black artists.

“I don’t remember anything quite like that,” del Rio said about that auction. “There were 20 people on each object. It was bananas.”

Since the pandemic, new works by in-demand artists have routinely appeared in the marquee auctions as the art world has rushed to cash in on the explosive global demand for contemporary art.

Many of the top auction prices for sought-after artists—including Rashid Johnson, Nicolas Party, and Dana Schutz—were set at Christie’s evening sales of 21st-century art.

Johnson, who has emerged as a leading voice (and one of the most commercially successful artists) of his generation, has been donating a painting to benefit sales almost every six months, resulting in ever-higher auction results over the past two years.

In May 2021, he donated Anxious Red Painting, which fetched $1.95 million at Christie’s to benefit Community Organized Relief Effort—more than six times its high estimate of $300,000. Six months later, in November 2021, he smashed this result with the $2.55 million sale of Bruise Painting “Or Down You Fall,“ sold to benefit ClientEarth, an environmental law charity. In November 2022, Johnson consigned Surrender Painting “Sunshine” to raise money for the Right of Return Fellowship to support and mentor formerly incarcerated creatives; it was a new auction record yet again, at $3 million (the prices include Christie’s fees).

Rashid Johnson at Hauser & Wirth Menorca. Artwork © Rashid Johnson, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo by Daniel Schäfer.

Johnson’s primary-market prices have increased as well during this period. His large “Bruise” paintings, shown at David Kordansky Gallery in 2021, were priced at $600,000 to $1.2 million. Last June, large new paintings exhibited at the Hauser & Wirth branch in Menorca were offered from $975,000 to $1.75 million, according to a person familiar with prices.

Representatives for the galleries didn’t respond to my requests for comment on whether the increase in Johnson’s primary market prices were influenced by these results.

In addition to generosity and access, there’s another big consideration when it comes to the lofty prices achieved at charity art sales: their potentially tax deductible value. Opinions on this topic vary.

“There may be circumstances when buyers could seek a deduction,” a Christie’s spokesperson said. “But they should always consult a tax advisor.” (The house sold more than $2 billion work of art for charitable causes in 2022, in large part thanks to the estates of Paul Allen and Doris and Thomas Ammann.)

Auction houses also defer these questions to the charities themselves. The Norton Museum, which raised $1.5 million from its most recent live and silent auctions, encourages donors to consult with their tax advisors.

“That said, yes, we do provide buyers with a fair market value and note that any amount paid in excess of that may be tax deductible,” a Norton spokeswoman said via email.

That doesn’t sit well with Ralph Lerner, co-author of Art Law, a must-have opus on the subject that is now in its 5th edition.

“That’s nonsense,” Lerner said by phone this week. “Some people argue that if the artwork’s market value is $400,000 and he paid $500,000, he would have been entitled to a charitable deduction of $100,000. Absolutely not. You can’t claim a charitable deduction because you bought it at a charity auction. The auction price is the fair market value. It’s not a cruise.”

The IRS will have to sort this one out, I guess. But it is telling that none of the museums that raised money for charity at Sotheby’s offered buyers supporting documentation for tax deductions. Caveat emptor, folks.

So, how do these auctions benefit the artists whose donations set the machinery in motion? Visibility, marketing, access to wealthy new fans, potentially higher primary-market prices, and a new benchmark for secondary sales. Dealers use these prices to pitch clients and sell out shows. Charitable works that are included in regular auctions are recorded alongside other results in the Artnet Price Database for posterity (unlike live and silent auctions conducted by nonprofits, which are not recorded).

“It’s just part of the cumulative impact,” said Marc Glimcher, president of Pace gallery, which represents Perez Simão and has a branch in Palm Beach. “This was a gift to a museum. We haven’t had a single piece come back for sale. Nobody wants to part with her paintings. The impact comes with where the secondary market is going.”

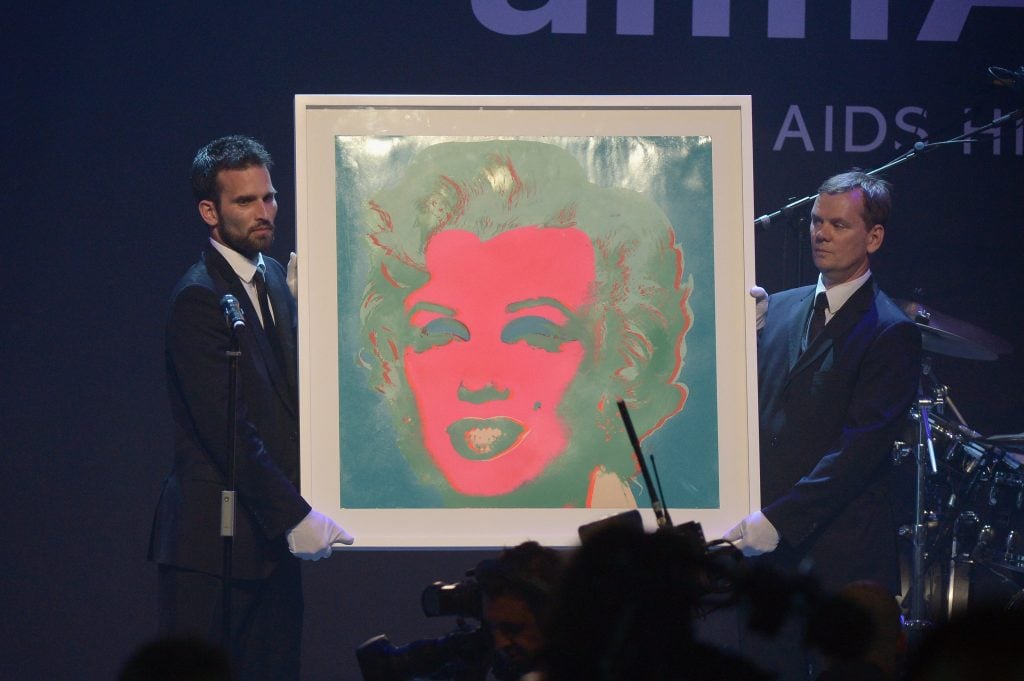

Auctioneer Simon de Pury conducts an auction on May 26, 2022, during the annual amfAR Cinema Against AIDS Cannes Gala at the Hotel du Cap-Eden-Roc in Cap d’Antibes. Photo by Patricia de Melo Moreira/AFP via Getty Images.

Kennedy Yanko made a star debut at amfAR’s Cannes gala in 2021, where her sculpture soared to $415,000 in bidding and was purchased by music entrepreneur and mega-collector Swizz Beatz. Her career has since skyrocketed. Next month she’ll have a solo show at Jeffrey Deitch’s gallery in New York, a coup for any artist.

Artists get celebrated. At amfAR, they walk the red carpet with celebrities and are called out by auctioneer Simon de Pury during the gala. The Norton put together a program for the attending artists, including private tours of its collection, which now includes billionaire Ken Griffin’s treasures, and of Beth Rudin DeWoody’s private museum, the Bunker. Hostetler Wrigley, a Norton trustee, hosted a cocktail reception for the 20 artists and 30 art dealers at her home.

“I can’t tell you how thrilled the board, the museum, and the community was that all of these artists and dealers not only agreed to donate works but also to come down to Palm Beach and celebrate with us,” said Hostetler Wrigley. “The energy they bring is critical.”