In 2019, after young New York-based painter Avery Singer parted ways with the dealer Gavin Brown, the art-world rumor mill had it that she was being hotly pursued by the biggest of the blue-chip galleries: David Zwirner and Gagosian.

When the dust settled, neither of them landed the artist, who instead made a splash by becoming the youngest stable member of mega-gallery Hauser and Wirth.

Singer was said to have been offered $1 million only to sign with Hauser and Wirth, a claim the gallery categorically denied. Yet an urban legend was born, and smaller galleries looked on at a glaring problem: how could they ever compete with the mega-galleries and their deep pockets?

Artist Avery Singer © Avery Singer.Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, Kraupa

Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin.

The Dance of Seduction

A good dealer can support an artist’s studio practice, develop a business strategy to manage supply and demand, and connect artists to new networks of collectors, critics, and institutions. Today, the Big Four mega-galleries (Gagosian, David Zwirner, Pace, and Hauser and Wirth) represent a combined 400 artists and occupy more than 330,000 square feet of exhibition space worldwide. Their clout allows them to make offers few others can.

When courting the artist Titus Kaphar last year—whose in-demand paintings have sold for more than $1 million at auction—Gagosian’s then-director Sam Orlofsky knew it was key to show commitment to Kaphar’s New Haven-based arts incubator program, NXTHVN. After Kaphar signed with the mega-gallery, Gagosian announced that it would fully endow the incubator’s paid apprenticeship program for high school students, throw its weight behind a professional development program, and sponsor the expansion of the program to other cities.

Meanwhile, Pace added six new names to its roster this year, including the world’s most expensive living artist, Jeff Koons, who left Zwirner and Gagosian in a major trade of allegiances.

Part of the deal, Pace vice president Jessie Washburne-Harris told Artnet News, is that the gallery was willing to step in and finance the production of the artist’s new body of work. (The perfectionist artist’s fabrication process, which is notoriously expensive and slow, has previously led to some high-profile lawsuits. His next body of work is expected to be ready at the end of 2023.)

Smaller galleries, of course, offer smaller—and sometimes quirkier—gifts and incentives.

To attract the attention of in-demand surrealist painter Jamian Juliano-Villani, Jasmin Tsou of JTT Gallery in New York sent her a huge case of her favorite Starbucks frappucino. Veteran dealer Andrea Rosen tried another approach, sending Juliano-Villani a crystal dildo as a nod to the artist’s impish sense of humor. Other dealers went for luxury goods: Italian dealer Massimo de Carlo sent her a Chanel handbag.

But for the artist—who says gifts are her “love language”—presents are only a starting point. Her relationship with Tsou, whom she calls her “original gallery mom,” has benefitted from the sustainable growth of her market. Her auction record of $405,781 was achieved just this past summer.

Jamian Juliano-Villani. Photo by Lia Clay Miller.

Building Meaningful Relationships

Indeed, dealers say courting and keeping artists isn’t all about offering cash and goods.

“I don’t believe the money runs the competition,” veteran gallerist Dominique Levy told Artnet News. “I think if we look at a relationship asking, ‘how can I make sure my artist has the creative and courageous conversation they need?’ then you shouldn’t be scared. If an artist is well taken care of and for the right reasons, they will not leave.”

Or, as mid-career painter Cynthia Daignault, who recently joined the roster at Kasmin Gallery, put it: “I want a love match, not a marriage of strategy or convenience.”

“There are plenty of places that would work with an artist out of pragmatics—their work sells or is popular with collectors or curators,” she added. “But I want the people I’m working with to really love and understand my work. Plus, I want them to trust me completely, so wherever my work takes me, they’re along for the ride.”

Artists with enough power to make such specific demands sometimes have the advantage of drawing interest from multiple dealers.

“Sometimes, you do clearly see that you are competing with other galleries for the beginning of a new relationship, and I think the best thing to do is to really be authentic in your approach,” Nick Olney, Kasmin’s managing director, told Artnet News.

“If I put myself in the shoes of an artist, it could potentially give me pause if a gallery just wants to throw money around to entice me, versus [showing] a clear commitment to what their approach is going to be in handling the artwork and putting it forward in the exhibition forum.”

That means there is no one-size-fits all approach. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, who works with blue-chip dealers Lisson, Continua, and Max Hetzler, said his relationships were founded on identification.

“If a gallery cannot step forward when an artist is in difficulty, I don’t think it is a trustworthy gallery,” Ai told Artnet News. “The most memorable thing is that when I disappeared in China for 81 days, both of my galleries made a huge effort in their capacity to demand my release.”

Washburne-Harris of Pace said Koons joined the gallery in part because he appreciated that it was “at core, a family-run business,” which reminded him of working with his first important dealer, Ileana Sonnabend.

“That’s really the core of what we’re trying to look for when we engage in these conversations—what can we do for them that another gallery is not providing,” she said.

Ai Weiwei’s ‘S.A.C.R.E.D’ at his landmark art exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts on September 15, 2015 in London, England. Photo by Alex B. Huckle/Getty Images.

Be Flexible and Open to Adjustments

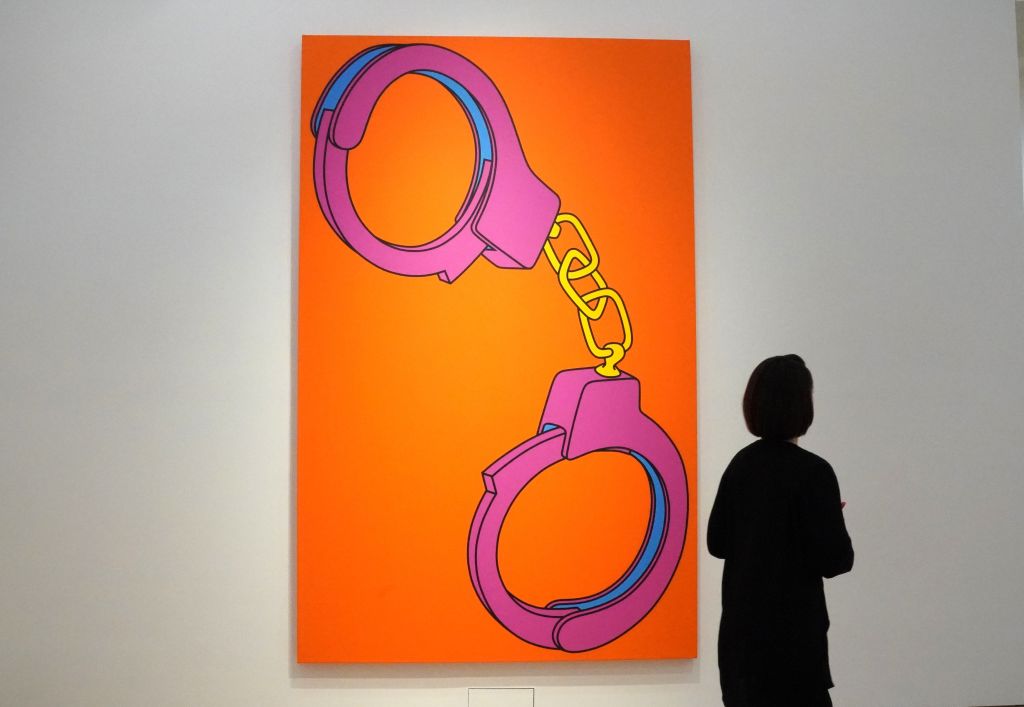

Like all relationships, those between dealers and artists are bound to change over time, and flexibility is essential. “I never want to be in a position where the artist feels they have been bought, or handcuffed,” Levy said.

For her, this means allowing artists to develop their careers without being bound to restrictive covenants like exclusive worldwide representation deals. This allows artists to work with galleries in other countries that can serve them in different ways. It also means being open to rearranging financial terms.

“I think at the beginning, the fair split is 50-50 [between artists and dealers on sales], because you are embarking on an adventure together that is untested, in uncharted territory,” she said. But “when an artist has established a certain level of career, that’s when you redefine the partnership.”

Levy said she has a range of commission splits with artists that vary from the traditional 50-50 to 60-40; she even has one 70-30 relationship. She stressed that this negotiation must not be rooted in “fear and territoriality” but in response to the varying needs of artists. Do they require extensive resources? Full-time staffs? Or simply space to work and grow?

Levy added that she often embraces a breakeven if that is meaningful to her artists.

“Don’t forget, they bring the creativity,” she said. “They are the reason we exist, and I feel the market has forgotten that.”

Above all, she said, it’s about creating a mutually respectful partnership.

“You don’t want to squeeze your artist, and you don’t want the artist to squeeze the gallery.”