“See Hamlet, Act I, Scene IV.”

So read a footnote in the dramatic pages of a 2018 lawsuit that a billionaire collector filed against international art star Jeff Koons and his then dealer, Larry Gagosian. The collector, MoMA trustee Steven Tananbaum, alleged that something was “rotten in the state of Denmark” after he got fed up with years-long delays on the delivery of three major Koons sculptures that he had already shelled out millions for.

Tananbaum eventually settled with the gallery and the artist’s studio on confidential terms, and today he “still enjoys a productive relationship with Larry Gagosian and considers Jeff Koons to be one of the world’s great living artists,” according to one of his attorneys, John Cahill.

While it’s no secret in collecting circles that Koons is not an easy artist to buy, the high-profile lawsuit—one of at least three sparked by fabrication and delivery delays in the past decade—further reinforced the image of Koons as an artist who is obsessively, notoriously attentive to detail. Combined with his grand ambitions to produce very large, extraordinarily shiny sculptures with extravagant price tags, it has frequently caused headaches for the artist and his galleries alike over the course of his four-decade career.

Now, the artist’s new dealers at Pace Gallery, which announced exclusive representation of the artist in April after he left both Gagosian and David Zwirner, are trying to get a handle on the artist’s supply issues—and a market that’s seen better days.

Jeff Koons, Balloon Venus Lespugue (Red) (2013–19). © Jeff Koons. Image courtesy of David Zwirner.

Curbing the Futures Market

One of the first changes Pace will make is to stop selling and invoicing for artworks that have not yet been fabricated.

“That’s definitely part of our new strategy,” Pace vice president Jessie Washburne-Harris told Artnet News. “We’re not selling any artworks or invoices until the artwork is fabricated, and that’s a very different strategy than Jeff’s previous galleries. Everything that we’re doing is very innovative to where Jeff’s work is right now.”

Not only did Koons’s previous galleries sell works before they were made, he is also perhaps the only artist known to have a stock market-like “futures” platform, where, in the early ’00s, people were buying options on not-yet-created works, for prices around $2 million, and then turning around and re-selling them.

The gallery is also taking a far more hands-on approach to Koons’s production process. “We figured out a way to create a production schedule with his fabricator in Germany and stepped in and helped to produce this new body of work, which he really wanted to finish,” said Washburne-Harris.

The new works will appear in a solo show at Pace New York in late 2023, for which Koons is making stainless steel replicas of porcelain figurines.

“Getting some discipline back into Jeff’s market and production is really key,” said one advisor who has dealt extensively in the artist’s works. “He kind of hit bottom and the market wasn’t very strong. There’s a feeling that he was over-producing and played his hand a little bit, particularly on the ‘Gazing Ball’ paintings, which did not meet with critical success, nor did his paintings of the Liberty Bell or the Hulk.”

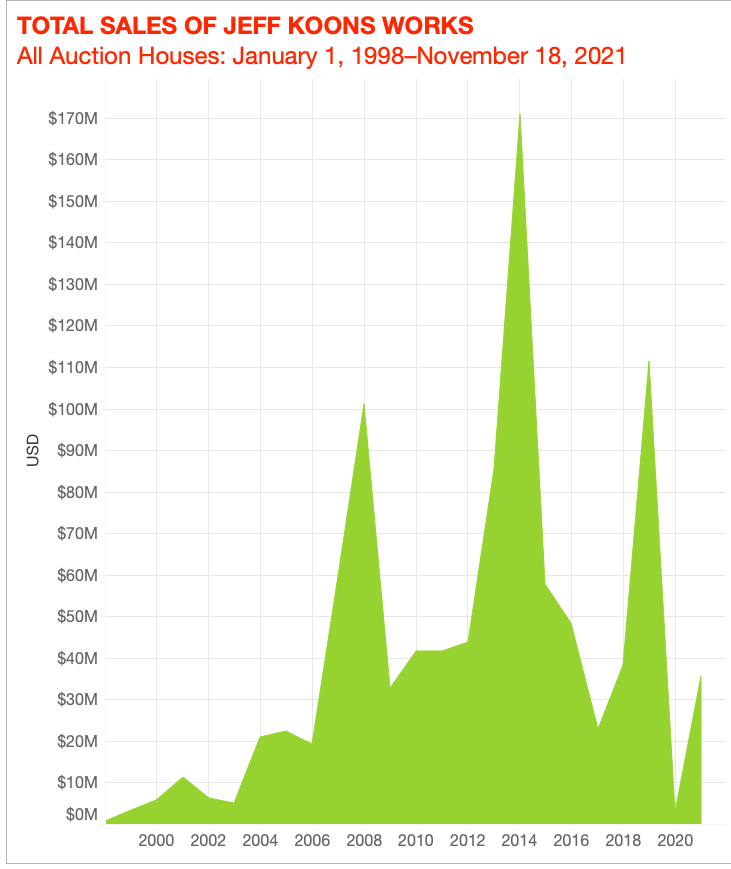

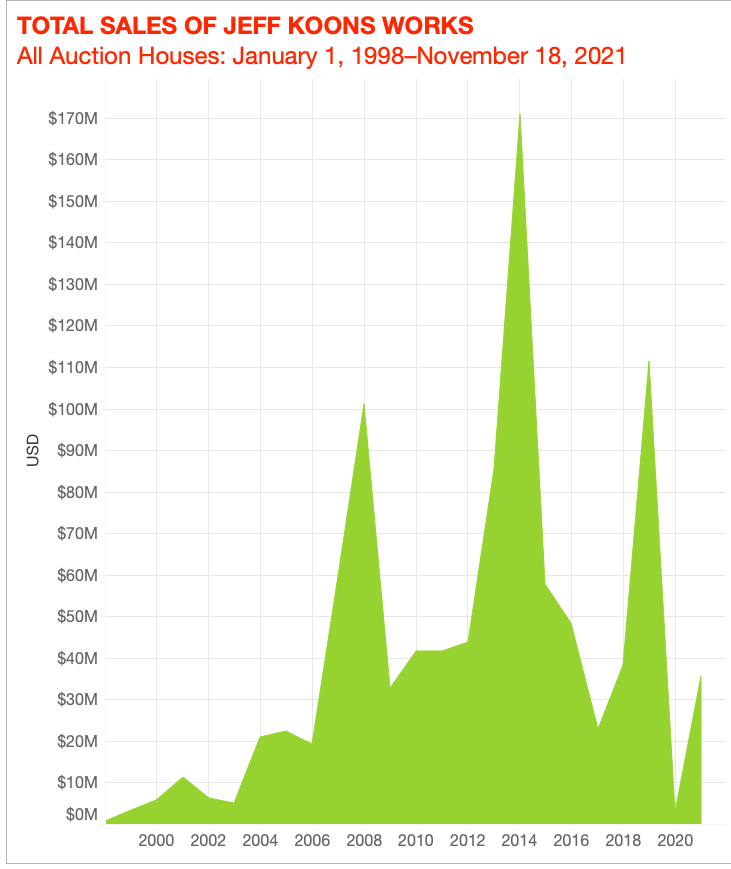

© Artnet Price Database & Artnet Analytics.

Auction data back the advisor’s claims. It’s difficult to reconcile how the market track record of Koons, who twice smashed the record for most expensive living artist at auction in the last decade, can now look so tepid and troubled.

After peaking in 2014 at more than $150 million, the artist’s overall auction volume has been trending downward. In 2020, it was down to less than $3 million, although the pandemic played a role in that. This year, as auctions resume more normal proceedings, the sales have picked up some—to $35.7 million to date—but that’s still a long ways off from earlier years. Of the 239 lots offered this year, 48 (or 20 percent) have failed to sell.

At Christie’s in May 2019, Koons’s stainless steel Rabbit (1986), considered the holy grail of the artist’s work in elite collecting circles, sold for $91 million, smashing his previous $58.4 million record, which was set for Balloon Dog (Orange) in 2013, when his market was clearly far stronger. However, despite the lofty 2019 achievement, the single work accounted for the lion’s share of the artist’s roughly $100 million auction total that year, according the Artnet Price Database. Some experts attribute the price to a dearth of sought-after material on the market, such as the artist’s earlier works.

(L-R) Sheikha Reem Al Thani, Jeff Koons and Massimiliano Gioni at a press preview of Jeff Koons’ exhibition “Lost in America” on November 20, 2021 at Qatar Museums. Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for Qatar Museums.

‘A Great Storyteller’

Despite Koons’s various market woes, institutional interest in his oeuvre may be stronger than ever. Last week in Doha, Qatar Museums opened “Jeff Koons: Lost in America” at QM Gallery Al Riwaq, an expansive exhibition space on Doha’s famous Corniche promenade.

The event marks Koons’s first major show in the Gulf region, and the second one curated by New Museum artistic director Massimiliano Gioni. “It was such a special collaboration that Jeff asked me to curate his show in Qatar, where I had first worked in 2012 organizing a major Takashi Murakami show,” said Gioni.

With 60 works (including loans of major pieces such as Rabbit, Balloon Dog, Play Doh, Moon, Balloon Venus, Balloon Monkey, Balloon Flower, and the new Party Hat) in an exhibition space of 35,000 square feet, it’s one of Koons’s largest shows ever.

The artist’s enduring popularity at museums may have something to do with his broad public appeal. The artist is “a great storyteller,” said Phillips deputy chairman Jean-Paul Engelen, who flew to Doha for the opening. “He does it in a way that everybody understands. You don’t need a higher education to understand where he’s coming from, because everybody has childhood memories about the objects in their parents’ house. He touches on the story of high culture and low culture.”

A view of of Jeff Koons’ exhibition “Lost in America” on November 20, 2021 at Qatar Museums Gallery ALRIWAQ in Doha, Qatar. Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for Qatar Museums.

For some, however, the artist and his highly publicized market are hard to separate.

“I think the preoccupation with Koons’s prices—when today, many other artists also obtain high prices in the marketplace—is connected to the complicated dynamic between collectors, museums, and critics and the art world’s relationship with wealth,” said Joanne Heyler, founding director of the Broad Museum, which is home to a large collection of Koons’s art. “Which, in turn, of course, gets to key provocations within Koons’s work: What is good taste? Why is this object in good taste and that one not?”

Jeff Koons, Rabbit (1986) in a custom built display space at Christie’s. Photo by Eileen Kinsella

Art advisor Lisa Schiff said that the extravagant prices and sometimes questionable subject matter (namely Koons’s “Made in Heaven” series with his former wife, porn star Ilona Staller) have ultimately overshadowed his career.

“For me, at a certain point it became so much about the money that I couldn’t look at a shiny outdoor sculpture without thinking of dollar signs,” she said. “When it becomes too much about the money, it’s just not interesting. I feel like where he started is just somewhere so different from where he went.”

Gioni, for his part, said that he tries “to separate the player from the game. In other words, was Titian a lesser artist for painting Charles V?”

Time will tell whether Pace can revive the artist’s market. But in the meantime the gallery is getting set to parade its new prize to the art world. This week, it will show Koons’s work at Art Basel Miami Beach, and has announced a January exhibition at the new Palm Beach gallery it opened last year. On view there will be none other than Balloon Venus Hohlen Fels (2013–19), the mirror-polished stainless-steel sculpture that was one of the three works in Tananbaum’s (now settled) lawsuit.

“This work is made and exists,” said Pace’s Washburne-Harris. “Lets talk about the work.”