The Innovators is a five-part series of interviews with change-making art-world figures featured in the 2022 Artnet Innovators List.

Sandra Jackson-Dumont, the director and CEO of the forthcoming Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles, has a gift for unexpected points of entry. During the most recent meeting of the American Alliance of Museums, she opened her keynote speech with a love song by ’70s soul singer Donny Hathaway. “Don’t you want people to see your institutions that way?” she asked the audience of museum professionals, snapping and swaying along to the lyrics. From there, she eased into an incisive discussion about institutional public engagement, not skipping a single beat.

For more than 20 years, Jackson-Dumont has been a force in education and public programming, launching enormously popular initiatives including the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s teen takeover night and the Seattle Art Museum’s after-hours soirees. These programs, like her keynote speech, energize audiences by blurring distinctions between fine art and popular culture, opening new doors to visitors who might have previously felt unwelcome.

That mission continues at the interdisciplinary Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, founded by Star Wars creator George Lucas and Ariel Investments co-CEO Mellody Hobson, and slated to open in 2025. With a 100,000-piece collection comprising painting, filmmaking, graphic design, and much more, it promises to reinvent the artistic canon and “move people to think about the impact of images on our world.”

Artnet News recently selected Jackson-Dumont as one of its 2022 Innovators, a list of 35 professionals pushing the art industry forward. The conversation with her below, conducted by Artnet News contributor Janelle Zara for the Art Angle podcast, is an expansion of Jackson-Dumont’s entry on the Innovators List, in which she discusses her longtime commitment to transforming museums’ rapport with the public, the Lucas Museum’s record-breaking $15.3 million Robert Colescott acquisition, and the museum’s goal to do for narrative art what the Whitney did for American art.

An aerial rendering of the Lucas Museum, slated to open in Los Angeles in 2025. Courtesy of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art

Can you describe George Lucas and Mellody Hobson’s vision to create this museum? What was the genesis, and what do we talk about when we talk about narrative art?

The term narrative art has been used since at least the 1960s, and it can be seen through much of the world’s artistic output for millennia, whether it originates in religion, myths, legends, history, literature, or in contemporary events. This museum is the first institution dedicated to exploring storytelling’s function across cultures, time periods, and regions. It’s akin to the Studio Museum’s dedication to Black artists wherever they are, or a place like the Whitney, an institution that would put an American imprint on the canon of art history. We are an institution that’s cutting a path in very much the same way.

We have fantastic works by everyone from Norman Rockwell to Frida Kahlo to Yinka Shonibare to Judy Baca. Talk about a great narrative landscape! George has been collecting art for four-plus decades, and he believes very strongly in the power of visual storytelling to reflect and shape societies. Mellody is also interested in the idea of what a museum could mean in society, and how it can drive opportunities for people from various backgrounds to come together. Before George and Mellody married in 2013, they were both collecting, but her focus was on modern and contemporary works, much of which was by African American artists. Their personal collections are separate from the museum’s collection, and so as an institution we’re acquiring works ourselves. But we’re constantly in conversation. They value a nuanced presentation of what narrative art is, and they’re really excited about us being an institution that not only presents ideas, but provides the site for discourse and dialogue about comfortable and uncomfortable issues.

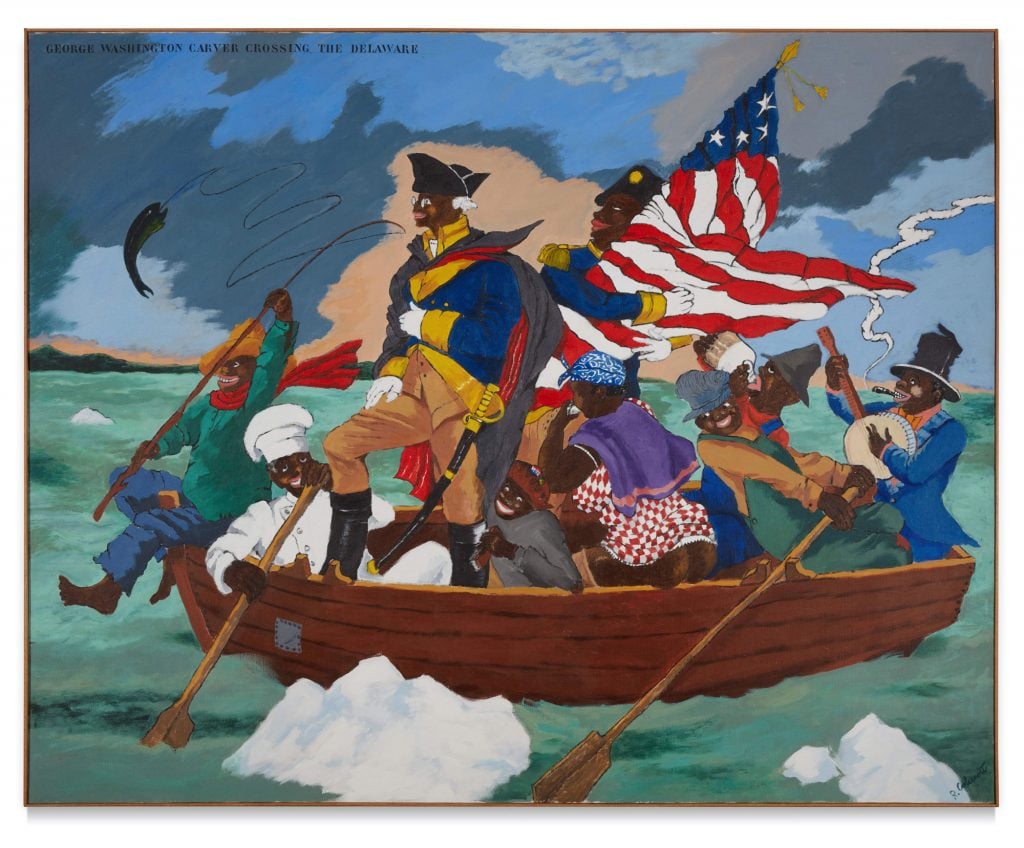

One of your headlining acquisitions is the painting George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook, Robert Colescott’s 1975 take on Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 painting Washington Crossing the Delaware. The purchase made headlines in 2021 after a reported seven-minute bidding war at Sotheby’s, and when the museum won for $15.3 million, it set a new record for an artist whose work has been historically undervalued. Why was it important for this work to be part of the collection?

This painting presents a radical and important alternative telling of a patriotic, visual narrative and mythology that has for so long grounded our national identity—you can’t study American history and not see [Leutze’s] work in your textbook. Colescott’s painting is both contemporary and historical, and it merges popular culture and art history. He was thinking differently about what the canon of art history could be for people of color. This work shows how a visual artist can change a story with complex emotions and narratives that will continue to be relevant across time, for decades after. I’m thrilled to say that this work will be on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the American Wing, not far from where the Leutze painting is. For the first time in history, we’ll have these two works in a conversation.

Robert Colescott, George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook (1975). Courtesy of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles, © 2021 The Robert H. Colescott Separate Property Trust/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

It’s been a longtime wish of yours to show these works together, right?

Yes, and it’s exciting to see it come to fruition. [Curator] Lowery Stokes Sims, who’s done such significant research and writing on Colescott’s work, is a long-term mentor who I respect and adore, and so to have this happen during her lifetime and mine feels like—wow! It’s also a great opportunity for us to look at the canon of art history differently. I keep saying that because it’s an important part of a more reflective and nuanced approach to art history than the one that’s historically been presented. I’m thrilled.

I’m interested in you having worked at the Met. I love the Met, but in many ways, it’s the opposite of what you’re describing. It’s a 150-year-old institution rooted in precedent—whether that’s how the staff is organized, what counts as art, how it’s categorized. When you were offered this job, what kind of opportunities did it represent for you to challenge these ideas? What precedents do you hold on to, and what do you leave behind?

As far as staffing structures and organizational hierarchies go, I think there are some that work really well, but there’s an opportunity for us to go against the grain of stereotype. Who gets to sit in these roles? Who are the actors that shape these institutions? It’s imperative for us to talk about the professional makeup of museums and that people see themselves being able to contribute.

Contrary to what a lot of people believe, the Met is a living, breathing vessel that evolves and transforms. I did come to the Lucas Museum and naively think that I wouldn’t have to retrofit anything, but it’s not detached from the history of art and the history of museums. While there is this amazing opportunity for us to really think differently about how museums work and what they mean in the world, we’re working against this longstanding history of the role that museums have played in society. When people say, “Oh, that’s so important, that should go in a museum,” it’s because it’s something we value and we think it needs to be cared for over time.

What we’re trying to accomplish, and what I’ve invested in my career in, is making museums places of social learning and social engagement. I want us to be a museum that people walk up to and say, “I don’t know what’s going on there, but I’m sure today something interesting is happening.”

A rendering of the Lucas Museum lobby. Courtesy of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art

You’re describing a lot of trust—trust that you’ll find something for you—and I think that’s a feeling that people really don’t have about museums. I think of museums as a place where history is presented to you. How do we transform the passive museum experience into an active one?

Historically, it has been exactly the prescriptive place you said. But imagine if a museum was a place where you come not just to see things, but to be seen. What if a museum acknowledged you as someone important, whose stories are important? And what if it had a personality that you wanted to spend time with?

Our job is to figure out the intersection between important historic or contemporary works and what matters in people’s everyday lives. We also have to create this “fear of missing out” situation—where people are excited about going to the museum, not only about the objects, but also about the people they might meet there that day.

I want to ask you about your personal history with art. I don’t know if my father has ever been to a museum in his life. I know that my mother has, because I brought her to one. I wanted to ask you, because you studied art history at college, whether you had a strong background that set you up on this path?

Oh, no, not at all. It’s funny that you mentioned your parents, because I had the same experience. My mother’s from rural Mississippi, and I’d grown up in San Francisco never really going to museums. For me, college was less about what fed my soul than doing something that allowed me to contribute to society. I really wanted to be a doctor, so I spent my first four years of undergrad studying biology, until I changed my major to art history in senior year. I saw a movie called Boomerang where Halle Berry studied art history and volunteered in Harlem teaching kids’ art classes, and I found that to be really interesting and more aligned with how I wanted to be in the world. Then I saw a special on public television about the Studio Museum that talked about this incredible museum in Harlem that was dedicated to Black art and Black people.

There were all these tiny incremental things, almost bread crumbs, that led me here. I’m most interested in trying to create transparent ways that people can get engaged in this field, versus it being by chance.

I wanted to tell you that your speech at the American Alliance of Museums conference made me really excited to talk to you. You took a moment to vibe to this Donny Hathaway song before you said something really important—that “museums are experiencing an ethical, social, and cultural seismic shift.” What did you mean by that? What kind of obstacles, but also opportunities, do these shifts present?

Museums realize that the world has changed around them, and so they have to meet the moment. That means you can’t just be for a small subset of people, and you have to be comfortable with having uncomfortable conversations—you have to prepare to not just talk about art, but talk about the world. You can’t have a situation where George Floyd is murdered and go back to talking about Attic black-figure pottery. You have to think about making space for us to talk about this moment. The days of isolationist approaches to museums are long gone. The seismic shift relates to a desire on behalf of cultural workers to make meaning that goes beyond a wall text.